Cases of intra-abdominal actinomycosis have been described years after cholecystectomy, although it is a rare complication. Due to the slow growth of Actinomyces, symptoms can present months or even years after surgery.1,2

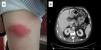

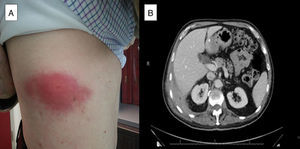

We present the case of a 71-year-old patient who underwent delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Four years later, he presented with dyspnea, cough, asthenia and pleuritic pain in the right hemithorax. On physical examination he was found to have a hard, painful swelling on the lateral region of the right hemithorax (Fig. 1A), with absent breath sounds. Acute phase reactants were elevated, and the chest radiograph showed right pleural effusion. Computed tomography (CT) revealed thickening of the pleura of the right posterolateral costophrenic angle (2.5-cm in thickness) and a hypodense area inside with extrapleural fat involvement, muscle thickening and pleural effusion (Fig. 1B). Thoracocentesis was performed and a fluid consistent with an exudate with predominantly polymorphonuclear cells was obtained, which later became mononuclear cell-predominant. Microbiology and cytology were negative. Needle biopsy of the pleural thickening reported an inflamed abscess. Ultrasound of the rib region showed a 3-cm hypoechoic mass, with multiple echoes, consistent with an abscess. This was aspirated and purulent matter was extracted; subsequent culture revealed Actinomyces israelii and Escherichia coli. From that time, the patient presented a chest wall fistula. Intravenous (i.v.) amoxicillin/clavulanic acid treatment was started for 14 days, followed by a further 4 weeks of i.v. penicillin. After 6 weeks of i.v. antibiotic, clinical improvement was observed and the fistula closed. Oral amoxicillin was continued until the patient had completed 12 months of treatment. A follow-up CT scan performed after the patient had been on antibiotics for 5 months showed a reduction in the effusion, with no changes in the pleural thickening.

A. israelii inhabits the oral cavity and upper gastrointestinal tract. Infection can occur when the mucosal barrier is damaged due to endoscopic manipulation, surgery or immunosuppression. Sulfur granules are characteristic on histological examination, but definitive diagnosis is made with microbiological isolation.3 The infection is usually found in middle-aged men with poor dental hygiene, and is most often located in the cervicofacial area (50%), followed by the abdomen (20%) and chest (15%–20%).2

The most common cause of chest involvement is aspiration of secretions,2 and it can present as empyema, pneumonia that progresses to cavitation, and pericardial or diaphragmatic involvement.4

Symptoms are variable and non-specific, and the patient may be asymptomatic. Acute phase reactants are generally elevated.3

Initial treatment is i.v., with maximum doses for 4–6 weeks followed by oral treatment for a further 6 to 12 months. Penicillin is the drug of choice, although tetracycline, erythromycin or clindamycin may be also used in patients who are allergic to penicillin. Chest involvement usually requires more prolonged treatment than involvement at any other level. There are specific indications for surgery; as this alone is not curative, it must always be combined with prolonged high-dose antibiotic treatment.2,5

When diagnosed and treated promptly, the prognosis is good, with low mortality.5

Thus, pleural effusion with chest wall involvement in a patient with a history of laparoscopic cholecystectomy could be secondary to abdominal infection by Actinomyces.

Please cite this article as: Díaz Campos RM, López-Medrano F, Lalueza A, Granados Caballero F, Villena Garrido V. Derrame pleural secundario a infección por Actinomyces como complicación tardía de una colecistectomía laparoscópica. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:419–420.