Persistent interstitial pulmonary emphysema (PIPE) is a rare condition with a high degree of mortality and morbidity.1,2 It is associated with prematurity, distress respiratory syndrome, severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia and prolonged mechanical ventilation. However, it has also been reported in both non ventilated infants and full term infants.3,4 Emphysema arises from accumulation of air in the pulmonary interstitium which is due to a break in the alveolar wall that leads to air leakage and compression of adjacent structures.4–6 PIPE has two different forms: diffuse or localized in one pulmonary lobe (the lobes most commonly affected are the left upper and the right middle and lower lobes).1,5 Diffuse PIPE is most commonly associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia.4 PIPE is clinically and histologically distinct from congenital lobar emphysema.5,7

The diagnosis is suspected by clinical signs and chest radiography, and confirmed by chest computed tomography (CT).

Currently, there is not satisfactory treatment for this condition in infants, especially when the formation of bullae has led to mechanical problems in ventilation, pulmonary hypertension and compresses adjacent lobes. In severe emphysema in adults, one of the most promising approaches is lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS), in which lobar emphysema is resected to allow adjacent lung tissue to expand and improve respiratory function. Nevertheless, experiences with children are limited.8 Surgery could be an option when conservative treatment does not obtain satisfactory results, although indications for LVRS in infants need to be defined.1–3

A case of severe PIPE in a patient with bronchopulmonary dysplasia successfully treated with surgery is detailed next.

The female patient was born with a gestational age of 26+5 weeks with a birth weight of 788g after a controlled pregnancy and a spontaneous vaginal delivery. Partial pulmonary maturation was administered.

She had a 1min Apgar score of 6, being necessary orotracheal intubation due to ineffective respiratory effort.

She developed hyaline membrane disease, receiving a dose of surfactant. She was extubated 6h after birth, being supported with continuous positive airway (CPAP). She needed several reintubations in the context of apneas of prematurity, sepsis and intestinal volvulus needing aggressive ventilation parameters. She met criteria of severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks corrected gestational age (CPAP, 30% FiO2). At the age of 150 days, the patient had an exacerbation of her bronchopulmonary dysplasia with a new reintubation. She presented many recurrent airway obstruction episodes, which were refractory to treatment and caused hemodynamic instability to the patient. These symptoms and the radiological image suggested acquired interstitial emphysema. High resolution CT (Fig. 1A–C) confirmed PIPE with mainly affected right upper lobe, with severe mediastinal displacement. Bronchoscopy excluded an intrinsic airway obstruction. The patient was clinically unstable and had regular episodes of air trapping with desaturation and hypercapnia of difficult management, so surgical treatment was decided. Thoracotomy and lobectomy of right upper lobe was performed at the age of 160 days. The evolution after the surgery was favorable. She was extubated 5 days later. Afterwards, she remained in spontaneous breathing, with 25% FiO2.

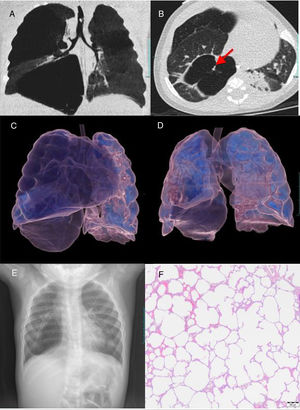

(A and B) Coronal (A), axial (B) CT images show areas of regional cystic hyper radiolucent and hyper expansion that involve right upper and lower pulmonary lobes and mediastinal displacement to the left. Note solid linear structure in the air filled cyst (arrow in B). (C) CT 3D volume rendering images before surgery. Hyper radiolucent cystic structures occupy right upper and lower lobes with hyper expansion and herniation of the right lung toward the left. (D) CT 3D volume rendering images after surgery. Right lung volume reduction and persistence of lower lobe cyst structure with minor hyper expansion. (E) Chest radiograph after surgery demonstrates right lung volume and mediastinal shift reduction with persistence of bullae in the right lower lobe. (F) Histologic examination (magnification ×40) of the upper right lobe shows severe evolved emphysema areas with marked alveolar hyper expansion due to air trapping, compressed parenchyma and generalized loss of interstitial connective tissue.

Histology confirmed the diagnosis of severe evolved emphysema (Fig. 1F). CT and chest radiography after surgery demonstrated the resolution of mediastinal displacement with persistence of bullae in the right lower lobe (Fig. 1D and E).

The patient was discharged at the age of 224 days with minimal oxygen supplementation and proper oral feeding.

PIPE which must be considered in the case of a compatible radiological image in CT in preterm infant with a history of respiratory distress, prolonged need for mechanical ventilation, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and torpid evolution from the respiratory point of view.1,2,5

The pathophysiology of this disorder was first described by Macklin and Macklin in 1944. PIPE is due to the disruption of the basement membrane of the alveolar wall, probably secondary to the aspiration of foreign material or partial or total occlusion of bronchi or bronchioles, which allows the entry of air into the interstitial space, conditioning compression of adjacent structures, as well as the appearance of emphysema.1,6

PIPE may be diffuse or localized in one lobe. In this case, the patient presented diffuse PIPE, with greater involvement of the right upper lobe.

The diagnosis will be made according to the clinical findings and the suggestive simple chest X-ray. Chest CT is required to confirm the diagnosis, being an excellent indicator of the severity of the disease. CT findings of this condition include multiple thin-walled, air-filled cystic structures (Fig. 1C). The line-and-dot pattern has been considered as a specific sign of PIPE.5,9

The therapeutic strategy to be followed in the case of PIPE is not clearly defined, especially in diffuse cases, and it will depend on the severity of respiratory symptoms and the stability of the patient.1–3

The conservative treatment of diffused cases includes mechanical ventilation in lateral decubitus position and selective bronchial intubation,1,10,11 high frequency oscillation ventilation, liquid ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.12–14

In refractory cases there is the possibility of LVRS. Localized lesions are more frequently diagnosed and surgically resected. There are only some exceptional cases described in the literature about diffuse PIPE treated by lobectomy or pneumonectomy with favorable evolution.1,3 We consider that surgical treatment favoring the re-expansion of the adjacent pulmonary parenchyma must be taken into account in these patients despite all the existing conservative therapeutic measures, since they may fail in this disorder. However, more studies would be needed, in order to establish the precise indications and the most appropriate time for surgery in both, located and diffuse cases and the fully monitoring of the evolution after it.

The patient presented in this article had a respiratory situation at the age of 5 months of difficult management with conservative measures and a vital risk due to the great pulmonary and hemodynamic compromise. The radiological findings were compatible with PIPE, so that performing a lobectomy to reduce the emphysematous area was decided. The pathological findings of the resected piece confirmed the diagnosis.

Thirty months after surgery, the evolution has been satisfactory with home intermittent oxygen therapy.