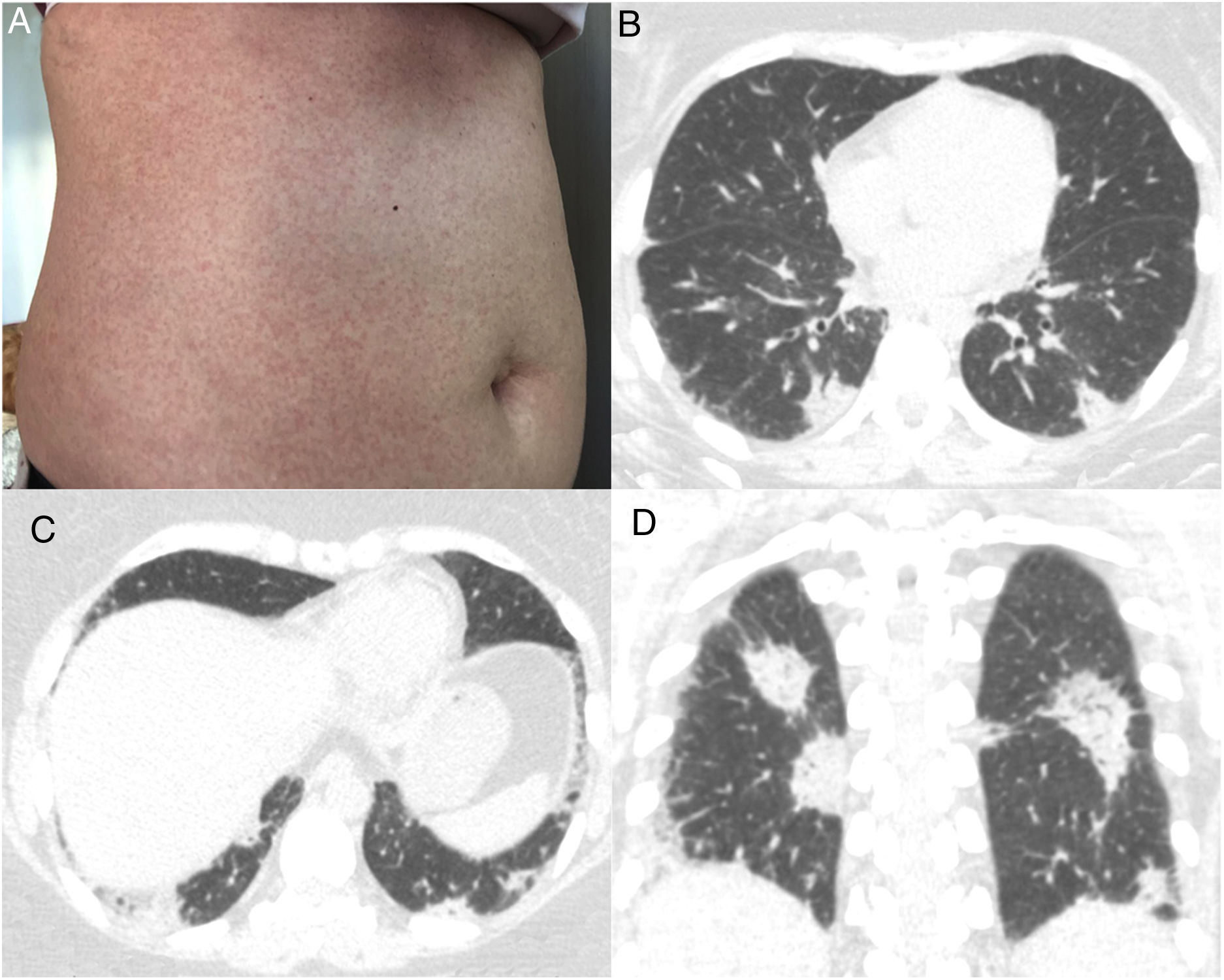

A 43-year-old immunocompetent woman presented to the emergency department with a history of 5 days of high fever (39°C), headache and diarrhea, evolving with a confluent maculopapular rash on her trunk (Fig. 1A). The patient was a resident of São Paulo, Brazil, in which an outbreak of measles was occurring. She had no history of measles vaccination. The diagnosis of measles was confirmed by serological positivity for serum measles immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies. No Koplik's spots were observed. One week after the onset of clinical symptoms, the patient began to present respiratory symptoms, with dry cough, dyspnea, chest pain and sore throat. Laboratory tests showed leukopenia with lymphocytosis. Blood cultures were negative. Chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated multiple peripheral consolidations, mainly in the lower lobes (Fig. 1B–D). Pulmonary embolism was excluded. Bronchoscopy was performed, and microscopic examination of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and cultures showed negativity for bacteria and fungi. The patient was managed solely with supportive therapy. Her condition and respiratory distress improved, and she was discharged 7 days after admission.

Measles is one of the world's most contagious viral diseases. Its re-emergence throughout Europe and North America has recently been reported.1–3 The disease has a prodromal phase of fever, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, similar to any upper respiratory tract infection. The characteristic measles rash appears a few days after the onset of fever. Koplik's spots, a pathognomonic sign, appear on the buccal mucosa as small white papules. Recovery typically occurs within 1 week of rash onset in people with uncomplicated measles.1,2,4–6

The clinical diagnosis of measles may be challenging in patients who present before the onset of rash or whose rashes are less apparent. Therefore, laboratory confirmation of the clinical suspicion of acute measles infection is highly recommended. The laboratory method used most commonly to confirm the diagnosisof measles is the detection of measles virus-specific IgM antibodies in serum or plasma. A real-time polymerasechainreaction assay for measles virus RNA in urine, blood, oral fluid or nasopharyngeal specimens can identify infection before measles IgM antibodies are detectable.2,5,6

Most measles-related deaths are caused by complications. The respiratory tract is a frequent site of complication, with pneumonia accounting for most measles-associated morbidity and mortality. Pneumonia can be caused by the measles virus, or by secondary viral or bacterial pathogens.3 These conditions can be difficult to differentiate based on imaging features, as the imaging findings of measles pneumonia are nonspecific. The most common CT findings are ground-glass opacities and consolidations with lobular or segmental distribution, nodules, interlobular septal thickening and bronchial or bronchiolar wall thickening. Other CT findings are bronchiolitis, hyperinsufflation, mosaic attenuation, pleural effusion and lymphadenopathy.1,4 Vaccinated individuals infected with measles can develop nodular pneumonia. These cases can be misdiagnosed due to the absence of specific IgM and typical symptoms.7 Vaccination is the best way to prevent measles, but the live-attenuated virus vaccine is contraindicated in immunocompromised patients.2,6 The management of patients with measles consists of supportive therapy to correct or prevent dehydration and, in some cases, to treat nutritional deficiencies, as well as early detection and treatment of secondary bacterial infections, such as pneumonia and otitis media. High doses of vitamin A have been shown to decrease mortality and the risk of complications. No specific antiviral therapy for measles exists, although ribavirin, interferon alfa, and other antiviral drugs have been used to treat severe cases.2,6