Bronchiectasis is caused by many diseases. Establishing its etiology is important for clinical and prognostic reasons. The aim of this study was to evaluate the etiology of bronchiectasis in a large patient sample and its possible relationship with demographic, clinical or severity factors, and to analyze differences between idiopathic disease, post-infectious disease, and disease caused by other factors.

MethodsMulticenter, cross-sectional study of the SEPAR Spanish Historical Registry (RHEBQ-SEPAR). Adult patients with bronchiectasis followed by pulmonologists were included prospectively. Etiological studies were based on guidelines and standardized diagnostic tests included in the register, which were later included in the SEPAR guidelines on bronchiectasis.

ResultsA total of 2047 patients from 36 Spanish hospitals were analyzed. Mean age was 64.9years and 54.9% were women. Etiology was identified in 75.8% of cases (post-infection: 30%; cystic fibrosis: 12.5%; immunodeficiencies: 9.4%; COPD: 7.8%; asthma: 5.4%; ciliary dyskinesia: 2.9%, and systemic diseases: 1.4%). The different etiologies presented different demographic, clinical, and microbiological factors. Post-infectious bronchiectasis and bronchiectasis caused by COPD and asthma were associated with an increased risk of poorer lung function. Patients with post-infectious bronchiectasis were older and were diagnosed later. Idiopathic bronchiectasis was more common in female non-smokers and was associated with better lung function, a higher body mass index, and a lower rate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa than bronchiectasis of known etiology.

ConclusionsThe etiology of bronchiectasis were identified in a large proportion of patients included in the RHEBQ-SEPAR registry. Different phenotypes associated with different causes could be identified.

Las bronquiectasias son la consecuencia final de múltiples patologías. Establecer la etiología tiene implicaciones clínicas y pronósticas. El objetivo fue evaluar la etiología de las bronquiectasias en una amplia muestra de pacientes, su posible relación con factores demográficos, clínicos o de gravedad, así como analizar las diferencias entre las idiopáticas, las postinfecciosas y las debidas a otras causas.

MétodosEstudio multicéntrico, transversal, del Registro Histórico Español de la SEPAR (RHEBQ-SEPAR). Se incluyeron prospectivamente pacientes adultos con bronquiectasias seguidos por neumólogos. Para el estudio etiológico se siguieron las recomendaciones y pruebas diagnósticas protocolizadas en el registro que posteriormente fueron recogidas en la normativa SEPAR de bronquiectasias.

ResultadosSe analizaron 2.047 pacientes de 36 centros españoles. La edad media fue de 64,9años y el 54,9% fueron mujeres. La etiología se identificó en el 75,8% de los casos (postinfecciosa: 30%; fibrosis quística: 12,5%; inmunodeficiencias: 9,4%; EPOC: 7,8%; asma: 5,4%; discinesia ciliar: 2,9%, y enfermedades sistémicas: 1,4%). Las distintas etiologías presentaban diferencias demográficas, clínicas y microbiológicas. Las bronquiectasias postinfecciosas y las secundarias a EPOC y asma presentaban más riesgo de tener peor función pulmonar. Los pacientes con bronquiectasias postinfecciosas eran mayores y se diagnosticaban más tarde. Las bronquiectasias idiopáticas predominaban en mujeres no fumadoras y se asociaban a mejor función pulmonar, mayor índice de masa corporal y menor frecuencia de infección por Pseudomonas aeruginosa que las de causa conocida.

ConclusionesLa etiología de las bronquiectasias se ha identificado en una gran proporción de los pacientes incluidos en el RHEBQ-SEPAR. Se pueden reconocer diferentes fenotipos relacionados con las distintas causas.

Bronchiectasis (BE) are the end result of many diseases. The etiological spectrum and the percentage of idiopathic BEs vary depending on the origin of the patient and the diagnostic protocol.1–11 Determining the cause of the process using an extensive protocol of diagnostic tests is justified, since identifying the etiology will affect treatment and prognosis.12–14 In a review1 of 35 European studies, 8 Asian studies, 6 from Oceania, 5 from South America, 1 North American, and 1 African study, the most frequently identified causes were: post-infective: 29.9%; immunodeficiencies: 5%; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): 3.9% (although this was an exclusion criterion in many studies)1–4; connective tissue diseases (CTD): 3.8%; allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA): 2.6%; ciliary dysfunction (CD): 2.5%; and asthma: 1.4%. In total, 44.8% were classified as idiopathic. Lonni et al.9 have published the largest cohort to date, with 1258 European patients. In Spain, no data focusing exclusively on the etiology of BE have been published, although some etiological data have been reported in other studies.15–20 The Spanish Historical BE Registry of the Spanish Society of Respiratory Disease (RHEBQ-SEPAR) was created in 2002 to establish standardized criteria for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with BE, and to determine the characteristics of this disease in Spain. This was an electronic database, accessible from the SEPAR website (www.separ.es/bronquiectasias), in which all respiratory medicine experts were invited to participate. The aim of this study was to evaluate BE etiology in a large patient cohort (included in the RHEBQ-SEPAR registry), the largest published to date, comprising a reasonably homogeneous sample, representative of the patients seen by pulmonologists. Another aim was to analyze the relationship between the different etiologies and demographic, clinical and severity factors, and the differences between patients with idiopathic BE compared to those with post-infective BE, and those with other etiologies.

MethodsDesign and PopulationThis was a multicenter, cross-sectional study of patients included in the RHEBQ-SEPAR registry. Adult patients with BE seen in respiratory medicine clinics in 36 centers in 11 autonomous communities were included prospectively between 2002 and 2011 (Table 1). Diagnostic and follow-up recommendations for inclusion and data collection were established and subsequently published in the SEPAR BE guidelines (NSBQ).12 Each patient was reviewed by the RHEBQ coordination team before being validated. If omissions or inconsistencies were detected, the investigator was asked to make the appropriate corrections for quality control purposes.

Distribution of Patients by Autonomous Communities.

| Autonomous community | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Andalusia | 283 (13.8) |

| Aragon | 88 (4.3) |

| Asturias | 51 (2.5) |

| Balearic Islands | 6 (0.3) |

| Canary Islands | 46 (2.2) |

| Cantabria | 5 (0.2) |

| Castile-Leon | 40 (2) |

| Catalonia | 930 (45.4) |

| Valencia Community | 178 (8.7) |

| Galicia | 28 (1.4) |

| Madrid | 380 (18.6) |

| Basque Country | 12 (0.6) |

Participants received detailed information, and confidentiality, data anonymization, and use of alphanumerical codes were guaranteed. Data were pooled for analysis. Registry users agreed to comply with the Data Protection Act.21

Bronchiectasis Diagnostic CriteriaBE can be diagnosed from clinical and radiological criteria, bronchography or computed tomography (CT) according to the criteria of Naidich et al.22 BE was classified as localized, bilateral, or diffuse (≥ 4 lobes). Patients diagnosed according to clinical-radiological criteria only were excluded.

Etiological CriteriaFor the etiological study, RHEBQ-SEPAR required the following variables and diagnostic tests12: sociodemographic characteristics; family history; smoking or exposure to toxins; history of radiation therapy or chemotherapy; infertility; lung infections (viral, pneumonia, mycobacterial, etc.), or infection in another site in childhood or before inclusion in the registry; concomitant diseases (diagnosed according to specific guidelines) such as rhinosinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux, atopy, asthma, ABPA, COPD, hematological diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, CTD, or transplantation. Clinical variables (age at onset of symptoms, cough, sputum, etc.) and physical examination data were also collected. Spirometry (forced expiratory flow [FEV1] in milliliters and as a percentage of predicted value),23 sinus radiography, sputum culture (including study of bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria), and clinical laboratory test results (including immunoglobulins,1-antitripsin) (if low, genotyping was recommended), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and rheumatoid factor were recorded. If immunodeficiency was suspected, immunoglobulin subclasses and antibody production were also determined, and in case of clinical suspicion of asthma and/or ABPA, skin tests and a RAST test for aspergillus were also performed. A sweat test and genetic study were also performed in patients with a family history or suspicion of cystic fibrosis (CF), and if infertility was reported, a seminogram was performed. If CD was suspected (in the absence of dextrocardia), tests for evaluating mucociliary clearance (saccharin, labeled seroalbumin, or nitric oxide) were recommended, and if screening was positive, ciliary ultrastructure testing was performed.12 Patients with symptoms of reflux were evaluated using pH-metry. The criterion for yellow nail syndrome was yellow dystrophic nails (with no fungal infection), combined with BE and sinusitis.12

CT was used to identify situs inversus, tracheobronchial abnormalities, post-obstructive BE, and emphysema. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was recommended in localized BE with no explanatory history.

BE was classified as idiopathic if the following diagnostic tests were negative: immunological study, sweat test, total IgE, skin prick, RAST-aspergillus, mucociliary clearance, α1-antitripsin, ANA, and rheumatoid factor.12

BE was considered post-infective in the presence of a clear history of previous respiratory infection, along with a clinical symptoms suggesting BE after the episode, consistent CT findings, and negative results on the tests mentioned above.12

Microbiological Evaluation and Severity ClassificationChronic bronchial infection (CBI) was defined as 3 or more positive cultures for a microorganism in a 6-month period.12 Data were collected from the 12 months before inclusion in the registry.

Patients were classified according to their FEV1 into 3 groups: FEV1%>80%, between 50%–80% and <50%.

Statistical StudyData were analyzed using the **R statistical package.24 Patients with CF were excluded from the comparative analyses. A descriptive analysis was performed, with central tendency measures and dispersion for quantitative variables (mean and standard deviation) and frequency distribution for qualitative variables. The Student's t test (or ANOVA for 3 or more categories) and the Chi-squared test for independent categorical variables were used to compare outcome variables with independent quantitative variables. Multivariate logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate lung function severity and idiopathic BE, using the Wald stepwise model, with p<0.1 as the entry criterion and 0.05 as the exit criterion, evaluating the odds ratio with the respective 95% CI. Statistically significant variables in the bivariate analysis were included as independent variables in these models. Non-CF BE (NCFBE) appearing as etiology in more than 1% of cases were included in some comparative analyses. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

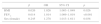

ResultsStudy PopulationA total of 2113 patients were included in the RHEBQ-SEPAR registry, recruited from 36 hospitals in 11 Spanish autonomous communities. Sixty-two patients diagnosed from a standard radiograph and 4 in whom the result of tests for etiological classification was missing were excluded (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Of these, 255 patients (12.5%) had CF,25 which, due to its particular characteristics, was excluded from the remaining analyses (Table 2). Characteristics of NCFBE patients are shown in Table 3. Mean age was 64.9 years, 54.9% were women, and 38.4% had a history of smoking.

Etiology of Bronchiectasis.

| Etiology | n=2047 (100%) |

|---|---|

| Post-infective | 613 (30) |

| TB | 380 (18.6) |

| Non-TB | 233 (11.4) |

| Idiopathic | 496 (24.2) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 255 (12.5) |

| Primary immunodeficiencies | 192 (9.4) |

| COPD | 160 (7.8) |

| Asthma | 110 (5.4) |

| Ciliary dyskinesia | 60 (2.9) |

| Connective tissue diseases | 29 (1.4) |

| Aspiration | 20 (0.9) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 13 (0.6) |

| Inhalation of gases | 6 (0.3) |

| Inhalation of drugs | 4 (0.2) |

| ABPA | 18 (0.9) |

| Congenital malformations | 14 (0.7) |

| Tracheobronchial disease | 11 (0.5) |

| Swyer-James syndrome | 3 (0.1) |

| Secondary immunodeficiencies | 11 (0.5) |

| HIV | 4 (0.2) |

| Post-transplantation | 4 (0.2) |

| Cancer | 3 (0.1) |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | 10 (0.5) |

| Bronchial obstruction | 6 (0.3) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 5 (0.2) |

| PTE pulmonary infarction | 5 (0.2) |

| Young syndrome | 5 (0.2) |

| Yellow nail syndrome | 4 (0.2) |

| Purulent rhinosinusitis | 4 (0.2) |

| Panbronchiolitis | 2 (0.1) |

| Hydatid cyst | 2 (0.1) |

| Other | 2 (0.1) |

ABPA: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism; TB: tuberculosis.

Clinical, Spirometric and Microbiological Characteristics of Patients with Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis.

| Total | n=1792 |

|---|---|

| Clinical data | |

| Age | 64.9±18.4 |

| <50, n (%) | 377 (21) |

| 50–75, n (%) | 787 (43.9) |

| >75, n (%) | 628 (35) |

| Age at diagnosis | 50.4±20.8 |

| Women, n (%) | 983 (54.9) |

| BMI | 24.9±4.8 |

| <20, n (%) | 217 (12.1) |

| 20–25, n (%) | 667 (37.2) |

| 25–30, n (%) | 645 (36) |

| ≥30, n (%) | 263 (14.7) |

| Smokers/former smokers, n (%) | 686 (38.3) |

| Sinusitis, n (%) | 428 (24.8) |

| Appearance of sputum | |

| Mucous, n (%) | 577 (38.4) |

| Mucopurulent, n (%) | 591 (39.3) |

| Purulent, n (%) | 334 (22.2) |

| Bronchiectasis site | |

| Localized, n (%) | 500 (27.9) |

| Bilateral, n (%) | 881 (49.2) |

| Diffuse, n (%) | 408 (22.8) |

| Spirometric data | |

| FEV1% | 67.3±23.9 |

| FEV1%>80%, n (%) | 599 (35.7) |

| FEV1% 50%–80%, n (%) | 624 (37.2) |

| FEV1%<50%, n (%) | 454 (27.1) |

| FVC% | 71.7±19.5 |

| FEV1/FVC% | 70.2±15.4 |

| Microbiological data | |

| Chronic bronchial infection, n (%) | 623 (34.8%) |

| Chronic bronchial infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, n (%) | 362 (20.5%) |

| Chronic bronchial infection caused by other microorganisms, n (%) | 239 (13.5) |

| Treatment with inhaled antibiotics, n (%) | 187 (11.3) |

BMI: body mass index; n: number; %: percentage.

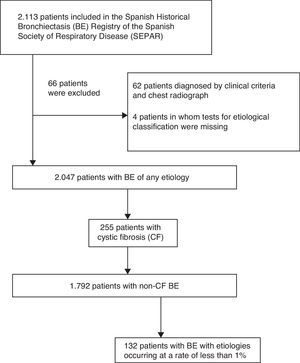

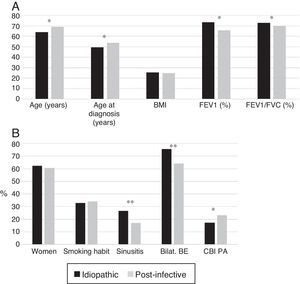

BE etiology was identified in 75.8% of patients, the most common cause being post-infective (30%). Rates of the different causes are shown in Table 2. Table 4 summarizes clinical differences by etiology. Patients with COPD had the highest mean age (Fig. 2A), while patients with BE due to CD were the youngest. Women were predominant among patients with idiopathic and post-infective BE, CTD and asthma, while more men had primary immunodeficiencies (PID) and, in particular, COPD (Fig. 2B). Patients with BE due to PID and CD presented more rhinosinusitis. Those with BE due to CD, PID, and CTD had predominantly bilateral disease (Table 5A).

Clinical Characteristics by Bronchiectasis Etiology.

| Patients | Idiopathic (n=496) | Post-infective (n=613) | Primary immunodeficiencies (n=192) | COPD (n=160) | Asthma (n=110) | Ciliary dyskinesia (n=60) | Systemic (n=29) | p ANOVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.9±17.4 | 69.1±16.4 | 53.8±18.7 | 76.5±10.3 | 66.8±16.9 | 42.9±18.8 | 70±13.8 | <0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 49.3±19.2 | 53.6±19.7 | 39.9±19.9 | 65.7±10.9 | 56.2±16.9 | 22.1±18.1 | 58.5±15.2 | <0.001 |

| Women | 309 (62.3) | 370 (60.4) | 88 (45.8) | 17 (10.6) | 75 (68.2) | 31 (51.7) | 20 (69) | <0.001 |

| Smoking habit | 163 (32.9) | 208 (33.9) | 64 (33.3) | 154 (96.2) | 31 (28.4) | 14 (23.3) | 8 (27.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI | 25.3±4.7 | 24.9±4.7 | 23.1±4.4 | 25.5±4.1 | 26.5±4.9 | 23.8±6.1 | 25.2±4.2 | <0.001 |

| Rhinosinusitis | 129 (26.7) | 100 (17) | 76 (42) | 11 (7.1) | 33 (31.1) | 43 (75.4) | 2 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| FEV1% | 73.3±22.6 | 65.6±23.1 | 77.7±21.9 | 46.8±19 | 63.4±23.4 | 67.1±24.2 | 71.4±22.7 | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC% | 72.8±14 | 69.6±14.8 | 77.9±14.4 | 56.5±15.1 | 66.4±13.5 | 73.2±14.7 | 70.8±14.3 | <0.001 |

| Chronic expectoration | 246 (49.6) | 325 (53) | 70 (36.5) | 104 (65) | 53 (48.2) | 51 (85) | 13 (44.8) | <0.001 |

| Hemoptysis | 24 (4.8) | 38 (6.2) | 2 (1) | 4 (2.5) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchial infection caused by any PPM | 157 (31.7) | 216 (35.2) | 69 (35.9) | 54 (33.8) | 31 (28.2) | 41 (68.3) | 9 (31) | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchial infection caused by PA | 85 (17.2) | 140 (23) | 21 (11.8) | 39 (24.4) | 14 (12.7) | 27 (45) | 8 (27.6) | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchial infection caused by HI | 52 (10.6) | 62 (10.2) | 34 (19.1) | 13 (8.1) | 14 (12.7) | 14 (23.3) | 1 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Inhaled AB | 50 (11.1) | 54 (9.7) | 14 (7.4) | 21 (14.3) | 5 (4.8) | 21 (39.6) | 3 (10.3) | <0.001 |

AB: antibiotic; BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HI: Haemophilus influenzae; PA: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; PPM: potentially pathogenic microorganism; n: number %: percentage.

Maximum and minimum values are highlighted in bold.

(A) Age by etiology * p<0.05; ** p<0.001. CD: ciliary dyskinesia; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PID: primary immunodeficiencies. Results expressed as percentages. (B) Sex by etiology * p<0.01; ** p<0.001. CD: ciliary dyskinesia; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PID: primary immunodeficiencies. Results expressed as percentages.

Bronchiectasis Site by Etiology.

| Localized (n=459) | Bilateral (n=829) | Diffuse (n=370) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic, n (%) | 121 (24.5) | 260 (52.6) | 113 (22.9) | ns |

| Post-infective, n (%) | 221 (36.1) | 260 (42.4) | 132 (21.5) | <0.001 |

| TB, n (%) | 150 (39.5) | 154 (40.5) | 76 (20) | |

| Non-TB, n (%) | 71 (30.5) | 106 (45.5) | 56 (24) | |

| Primary immunodeficiencies | 31 (16.1) | 112 (58.3) | 49 (25.5) | 0.001 |

| COPD, n (%) | 40 (25) | 91 (56.9) | 29 (18.1) | ns |

| Asthma, n (%) | 33 (30) | 62 (56.4) | 15 (13.6) | ns |

| Ciliary dyskinesia, n (%) | 10 (16.7) | 29 (48.3) | 21 (35) | 0.027 |

| Systemic, n (%) | 3 (10.3) | 15 (51.7) | 11 (37.9) | 0.040 |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ns: non-significant; TB: tuberculosis.

In total, 34.8% of patients with NCFBE had CBI, the most common microorganisms being Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA, 20.5%) and Haemophilus influenzae (HI, 11.8%) The different etiologies showed different microbiological patterns (Tables 4 and 5B). Patients with CD had the highest rates of CBI caused by different microorganisms and asthmatics had the lowest rates. CBI caused by PA was more common in patients with CD and COPD, and less common in PID and asthma.

Chronic Bronchial Infection Caused by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa (PA) by Etiology.

| PA yes (n=334) | PA no (n=1305) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic, n (%) | 85 (25.4) | 408 (31.3) | <0.05 |

| Post-infective, n (%) | 140 (41.9) | 469 (35.9) | <0.05 |

| Primary immunodeficiencies, n (%) | 21 (6.3) | 157 (12) | <0.01 |

| COPD, n (%) | 39 (11.7) | 121 (9.3) | ns |

| Asthma, n (%) | 14 (4.2) | 96 (7.4) | <0.05 |

| Ciliary dyskinesia, n (%) | 27 (8.1) | 33 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Systemic, n (%) | 8 (2.4) | 21 (1.6) | ns |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Of all NCFBE patients, 35.7% had FEV1>80%, 37.2% had FEV1 50%–80%, and 27.1% had FEV1<50%. COPD patients had a worse lung function and patients with immunodeficiencies had a better one (Tables 4 and 6). In the logistic regression model (Table 7A), risk factors associated with poorer lung function were female sex, older age, lower body mass index (BMI), and presence of CBI. Etiologies with greater risk of poorer lung function were post-infective BE and BE associated with COPD and asthma. Patients diagnosed with BE at a later age had better lung function.

Pulmonary Function by Etiology.

| FEV1>80% n=557 | FEV1 50%–80% n=577 | FEV1<50% n=417 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic, n (%) | 212 (46.4) | 157 (34.4) | 88 (19.3) | <0.001 |

| Post-infective, n (%) | 171 (29.9) | 238 (41.7) | 162 (28.4) | 0.001 |

| Primary immunodeficiencies, n (%) | 102 (54.8) | 59 (31.7) | 25 (13.4) | <0.001 |

| COPD, n (%) | 8 (5.3) | 55 (36.2) | 89 (58.6) | <0.001 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 32 (32) | 37 (37) | 31 (31) | ns |

| Ciliary dyskinesia, n (%) | 21 (36.2) | 20 (34.5) | 17 (29.3) | ns |

| Systemic, n (%) | 11 (40.7) | 11 (40.7) | 5 (18.5) | ns |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1: forced expiratory flow in 1s; ns: non-significant.

Logistic Regression. Characteristics Associated with Poorer lung Function.

| β | p | OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | <0.001 | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 0.84 | 2.31 | 1.81 | 2.95 | |

| Age | 0.03 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.03 |

| Age at diagnosis | −0.028 | <0.001 | 0.973 | 0.96 | 0.985 |

| BMI | |||||

| 20–25 | 0.021 | 1.00 | |||

| <18.5 | 0.55 | 1.73 | 1.08 | 2.77 | |

| 18.5–20 | 0.80 | 2.22 | 1.29 | 3.82 | |

| 25–30 | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.87 | 1.50 | |

| ≥30 | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.76 | 1.56 | |

| Etiology | |||||

| Idiopathic | <0.001 | 1.00 | |||

| Post-infective | 0.58 | 1.78 | 1.36 | 2.34 | |

| PID | −0.33 | 0.72 | 0.50 | 1.05 | |

| COPD | 2.11 | 8.22 | 3.86 | 17.52 | |

| Asthma | 0.73 | 2.07 | 1.28 | 3.36 | |

| CD | 0.58 | 1.78 | 0.95 | 3.33 | |

| Systemic | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0.51 | 2.66 | |

| Chronic bronchial infection | |||||

| No | <0.001 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.82 | 2.27 | 1.77 | 2.93 | |

BMI: body mass index; CD: ciliary dyskinesia; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PID: primary immunodeficiencies.

Dependent variable FEV1<80% vs FEV1≥80%.

Nagelkerke's R-squared: 0.233.

Patients with post-infective BE were older and were diagnosed later. More idiopathic BE patients were women and had bilateral involvement; they had lower rates of CBI caused by PA, higher rates of rhinosinusitis, and better lung function (Fig. 3A and B).

(A) Comparison of patients with idiopathic bronchiectasis and post-infective bronchiectasis * p<0.001. BMI: body mass index. Results expressed as means. (B) Comparison of patients with idiopathic bronchiectasis and post-infective bronchiectasis * p<0.05; ** p<0.001. Bilat. BE: bilateral and diffuse bronchiectasis; CBI PA: chronic bronchial infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Results expressed as percentages.

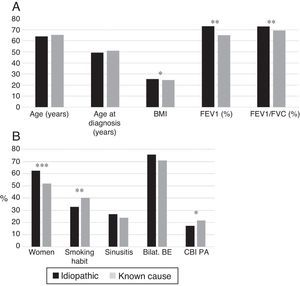

Idiopathic bronchiectasis were more common in female non-smokers, and was associated with better lung function, higher BMI, and a lower rate of CBI caused by PA than bronchiectasis of known etiology (Fig. 4A and B). In the logistic regression analysis (Table 7B), idiopathic BEs were associated with higher BMI, better lung function, and female sex.

(A) Comparison of patients with idiopathic bronchiectasis and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis of known etiology. n=1792. * p<0.05; ** p<0.001. BMI: body mass index. Results expressed as means. (B) Comparison of patients with idiopathic bronchiectasis and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis of known etiology. n=1792. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001. Bilat. BE: bilateral and diffuse bronchiectasis; CBI PA: chronic bronchial infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Results expressed as percentages.

Logistic Regression. Characteristics Associated with Idiopathic Bronchiectasis.

| β | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 0.026 | 1.026 | 1.003–1.049 | 0.026 |

| FEV1 | 0.014 | 1.014 | 1.009–1.019 | <0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 0.245 | 1.278 | 1.013–1.611 | 0.038 |

BMI: body mass index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1s.

Dependent variable: idiopathic vs known cause.

This study evaluated the etiology of BE, determined using a comprehensive standardized protocol of diagnostic tests, in the largest series of BE patients published to date. Although we cannot definitively establish the prevalence of the different etiologies, as this was a voluntary registry in which not all possible patients were included, the series is reasonably representative of Spanish BE patients, due to the participation of respiratory medicine units from different autonomous communities throughout the state.

BE etiology could be identified in a large proportion of patients enrolled in the RHEBQ-SEPAR registry (75.8%), as a wide range of etiological tests was recommended,12 and the patients were followed by respiratory medicine experts who generally follow the SEPAR recommendations. Cohorts published to date have shown widely differing results (26%–90%) due to differences in study populations, criteria for defining etiologies, diagnostic studies performed, and setting in which the patient was seen.1–11 Idiopathic BE was more common among study patients seen in general clinics1,10,11,26 compared to those seen in pulmonology or specific units,1,2,4,7,9,15,27 as is the case for patients enrolled in the RHEBQ-SEPAR registry. In a review of studies published in all countries, Gao et al.1 found a rate of 44.8% of idiopathic BE, and 41.1% when only European studies were analyzed.

In our study, the most common known causes were post-infective (30%), followed by CF, PID, COPD, asthma, CD, and CTD, in line with other studies.1,4,8,9,12,15,26,27 Of the 35 European studies reviewed by Gao et al.1 (6364 patients), the mean rate of post-infective BE was 31.2%; PID: 5.3%; COPD: 5.2%; CTD: 4%; ABPA: 2.8%; CD: 2.7%; asthma: 7%; and inflammatory bowel disease: 1%. In Spain,15–20 a study in 839 patients from 7 specific BE units that also used the NSBQ diagnostic protocol,12 aimed at constructing and validating the FACED score system15 found that the cause in 37% was idiopathic, in 29.3% post-infective, in 8.3% immunodeficiencies, in 3.5% COPD, in 3.2% CD, and in 2.1% CTD. However, a study in the US7 of 106 patients identified causal factors in more than 90% of cases, the most common being immune disorders and CTD, but this is probably because it was conducted in a highly specialized center that used in-depth immunological evaluations.7 In contrast, the RHEBQ-SEPAR registry was created by respiratory medicine experts, and in our setting, diseases such as CTD, and in some cases immunodeficiencies, atopic asthma and ABPA, are seen by other specialists, so this may have led to a lower rate of some of these diseases in our series.

In our series, infections, primarily tuberculosis, continue to be the most common cause of BE. However, the possibility remains that some cases of post-infective BE might be associated with an undetected immune or genetic alteration28 that would make the patient more susceptible to infection, particularly those with concomitant rhinosinusitis.2,4 In a systematic review1 in adults, tuberculosis was also the predominant etiology for post-infective BE, and was more common in Asia than in Europe.1,6,10,11,29 In children, pneumonia was the main cause.30 In developing countries1,6,29 or in indigenous communities,5,31 infections are also more prevalent, due to poorer health and social welfare conditions.

CF also accounts for a high percentage of BE, since the RHEBQ-SEPAR included all causes of BE and the numbers of adult patients with CF seen by pulmonologists in CF units is growing,32 most of whom participated in the registry.

Rates of PID were also high (greater than those published in Europe1,9 but lower than in the U.S.7), since detailed studies for ruling out or supporting this diagnosis were recommended12 before BE was classified as idiopathic.

In our series, BE was caused by COPD in 7.8% of patients. The earlier etiological studies did not include COPD,2,4 but since the publication of the studies by Patel et al.33 and Martinez-García et al.34,35 which showed that more than 50% of patients with moderate-severe COPD had BE, reported rates are increasing (11%–15%).8,9,27,36 As expected, patients with COPD were mainly men, with a history of smoking, older age, greater frequencies of CBI due to PA, and poorer lung function.

Clinical differences were found depending on etiology, with similar results to those published in other series.9,15,27 Patients with CD had the highest rates of CBI caused by different microorganisms and asthmatics had the lowest rates.1,4,9 CD and PID patients had higher rates of rhinosinusitis, in line with other studies.1,2

In our series, only 27% of patients had FEV1<50%, and in the multivariate analysis, the etiologies most often associated with poorer lung function were post-infective BE, BE caused by asthma, and particularly, BE caused by COPD. Patients with PID and idiopathic BE were those who had better lung function. Lonni et al.9 evaluated the relationship between different levels of severity and different BE etiologies, and did not find any important differences, except for a higher rate of severe forms among BE caused by COPD and a lower rate among idiopathic BEs, coinciding with our findings. The association between COPD and BE produces a more severe clinical phenotype with a poorer prognosis,9,34–36 although there is some debate as to whether the relationship is one of causality37 or comorbidity.38

When idiopathic BEs are compared to post-infective BEs, the idiopathic forms were diagnosed earlier, had more symptoms of rhinosinusitis, were predominantly bilateral, had better lung function, and a lower rate of CBIs caused by PA, in line with previous studies.1,4 In post-infective BE, the delayed diagnosis may be associated with a variable time between the initial infection that caused BE and the subsequent superinfection that would lead to the development of new symptoms.4,8,12

When idiopathic BE is compared to NCFBE of any known cause, we found that it presents as a special phenotype, characterized by lower smoking rates, higher BMI, better lung function, fewer CBIs caused by PA, and a clear predominance of women, confirming the findings of other published series in populations with fewer patient numbers.9,27 Several studies have been published recently36,39 that have tried to define specific BE phenotypes associated with prognosis, looking at factors such as age, exacerbations, or colonization by microorganisms, as well as the role of the different etiologies. Martínez-García et al.39 observed that the phenotypes associated with a better prognosis included a greater number of patients with PID, CD or idiopathic BEs than those associated with poorer prognosis, most of whom were COPD patients. Aliberti et al.36 also found that patients with idiopathic BE were also more inclined to present less severe phenotypes with less CBI caused by PA, while COPD phenotypes were more severe and more frequently involved CBI caused by PA. This also supports our results.

LimitationsAlthough our study has some very strong features, such as the inclusion of the largest series of BE patients followed by pulmonologists from different Spanish autonomous communities, and the use of a comprehensive standardized protocol of diagnostic tests to evaluate the causes of BE, it also has limitations. Firstly, the exact prevalence of the different causes cannot be established, since not all BE patients are included, although in our opinion the study population was sufficiently representative. Data analysis was cross-sectional, so longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the relationship between etiology, clinical symptoms and disease progress. Finally, the dyspnea grade was not collected, so neither the FACED15 nor the BSI40 prognostic indexes can be calculated, which would have provided more complete information on severity.

ConclusionsThis study is the first analysis of the RHEBQ-SEPAR registry that explores the causes of BE in the largest series published to date. BE etiology was identified in a large proportion of patients (75.8%), the most common causes being post-infective (30%), followed by CF, PID, COPD, asthma, CD, and CTD. Different clinical phenotypes associated with etiology can be identified. Patients with idiopathic BE had less severe disease, higher BMI, better lung function, less frequent CBI caused by PA, and a clear predominance of women. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the relationship of BE etiology with clinical manifestations and progress of this disease.

AuthorshipCasilda Olveira, Alicia Padilla and Miguel Ángel Martínez-García have contributed to the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and to the preparation of the article, and are guarantors of the manuscript. The other authors contributed to data acquisition and critical review of the article.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank Francisco Rivas (Research Department, Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol, Marbella, Malaga) for his contribution to the statistical analysis of the data.

Please cite this article as: Olveira C, Padilla A, Martínez-García M-Á, de la Rosa D, Girón R-M, Vendrell M, et al. Etiología de las bronquiectasias en una cohorte de 2.047 pacientes. Análisis del registro histórico español. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:366–374.