Asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) involves patients with asthma-like characteristics who have been exposed to COPD risk factors and developed persistent airflow obstruction (PAO).1 These patients typically have more symptoms, lower quality of life, and a higher risk of exacerbations than COPD patients. According to the SEPAR consensus on ACO,2 diagnosis is made in patients ≥35 years old, with ≥10 pack-years smoking history, PAO, and either a current asthma diagnosis, a highly positive bronchodilator test, or elevated blood eosinophilia. In terms of treatment, ACO patients have a poorer response to inhaled corticosteroids than asthma patients, but monoclonal antibodies approved for asthma can also be used, although real-world data on benralizumab is limited.

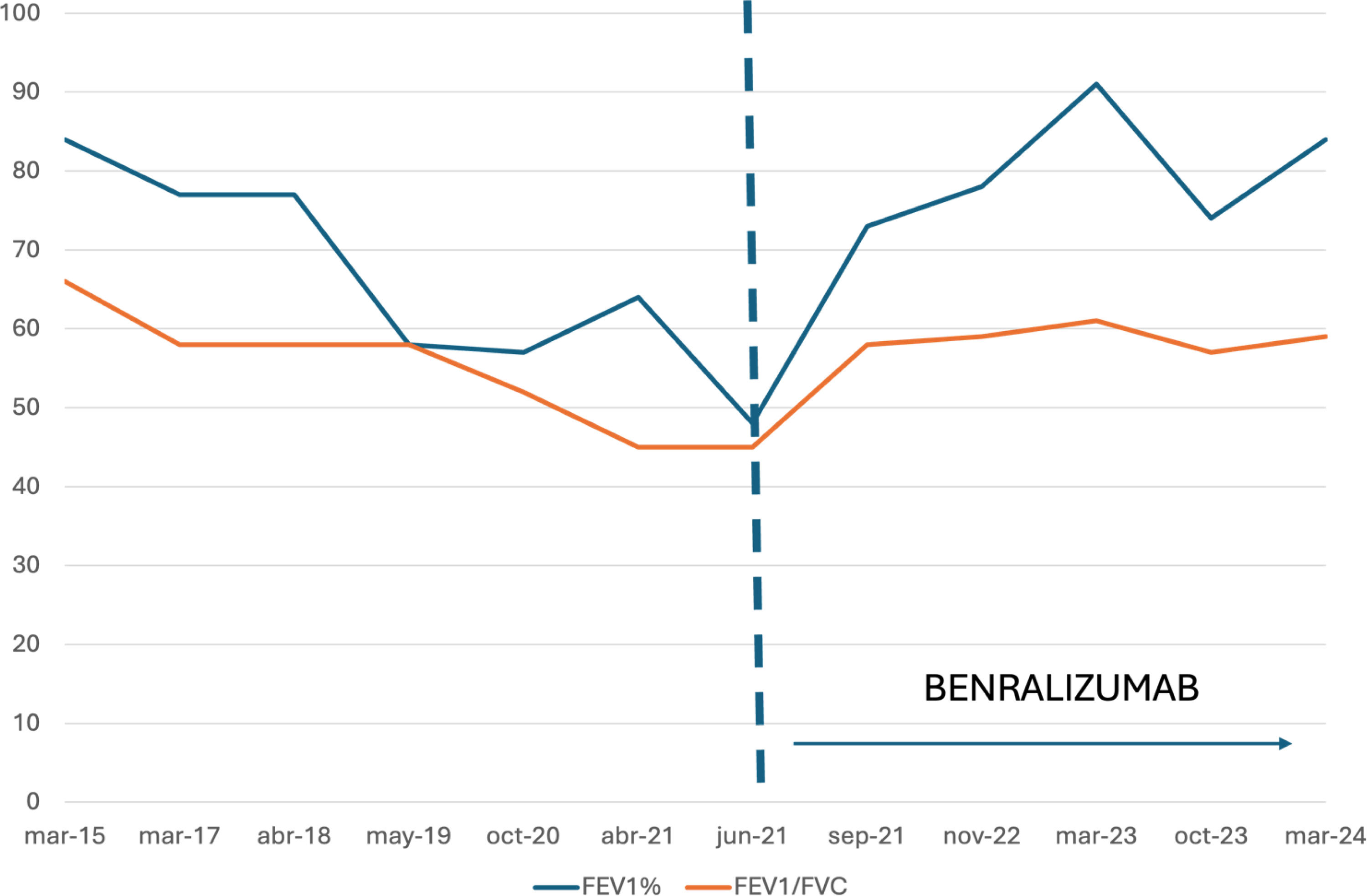

We present the case of a 54-year-old man ex-smoker with a 60 pack-year history, diagnosed with COPD and receiving triple inhalation therapy at a COPD clinic. He has undergone four surgeries for nasal polyposis, had PAO in all follow-ups, a positive skin test for dog and cat epithelia, and 6% blood eosinophilia (historically always above 460eosinophils/μl). He had dyspnea with mMRC grade 1, wheezing since age 30, 5–6 exacerbations per year in recent years treated with antibiotics and oral corticosteroids, including two hospitalizations in the last year. He was referred to our asthma clinic, where an obstructive spirometry with a negative bronchodilator test (FEV1/FVC: 45%, FEV1: 48%), FeNO 99ppb, IgE 259, and eosinophilia of 8.7% (700eosinophils/μl) were observed. He was diagnosed with ACO, inhalation therapy was adjusted, and due to persistent poor control, benralizumab treatment was initiated. Over the three years of follow-up after starting benralizumab, he reported significant clinical improvement (ACT 23), requiring only one course of antibiotics and oral corticosteroids. Additionally, his nasal polyposis improved, with no further surgeries needed. FeNO decreased to 24, and he still has PAO, but with an FEV1 >80%. See Fig. 1.

Given the clinical features consistent with asthma, recurrent nasal polyposis, frequent exacerbations despite appropriate treatment, and elevated T2 markers, along with COPD-related features such as a 60 pack-year smoking history and PAO, the patient was diagnosed with ACO according to the SEPAR consensus criteria.2 The lack of a standardized and universally accepted definition of ACO makes diagnosis complex, often leading to underdiagnosis. Furthermore, treatment options are limited as there are no specific biomarkers or standardized therapies. Clinical trials for biologic drugs in severe asthma excluded smokers, while COPD trials excluded patients with asthma features, leaving ACO patients unrepresented. This has resulted in ACO patients being less likely to receive biologics compared to those with severe asthma. Thus, real-world studies on the use of biologics in ACO are essential, though currently limited. The main real-world studies in ACO3,4 focused on omalizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab, and dupilumab. A recent study with benralizumab,5 using insurance database records in the US, lacked clinical or spirometric criteria, introducing potential selection bias. Nevertheless, all real-world studies confirm biologics’ effectiveness in ACO. This case highlights the clinical improvement and remarkable lung function response with benralizumab, emphasizing the need for accurate diagnosis and specific precision medicine treatments.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.