Since its very first edition, published in 1995, the Global Asthma Initiative (GINA) has depicted asthma therapy as a flight of stairs in which each step represents a level of treatment according to the severity of the patient.1 This approach has been adopted by the Spanish Asthma Guidelines (GEMA)2 and has been valuable for highlighting the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of the disease, the use of objective tests for diagnosis, the generalized prescription of anti-inflammatory medication, and the important role of education. However, a better understanding of the heterogeneity of asthma and its biology has revealed certain limitations in the guideline recommendations:

- -

The publication of the GOAL study in 2004 led to the implementation of a strategy of progressive escalation of asthma treatment to achieve control without taking into account the dose-response curve for inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).3 In placebo-controlled clinical trials with fluticasone propionate, 80% of the clinical benefit at 1,000 μg/day was achieved at doses of 70–180 μg/day and 90% at doses of 100–250 μg/day4; two studies with budesonide, randomized without a placebo arm, in which the authors examined drug doses >800 μg/day, indicated that there was a minimum additional clinical benefit (if at all) with doses of 3,200 μg/day compared to 1,600 μg/day, or 1,600 μg/day compared to 400 μg/day.5

Reddel et al. noted that a large percentage of overtreated asthmatic patients (approximately 50%) may achieve lower doses of ICS if long-term β-adrenergic agonists (LABA) are maintained, without increasing inflammatory parameters such as the fraction of nitric oxide in exhaled air (FENO) or eosinophil levels in sputum.6 While it is true that GINA and GEMA recommend reducing the dose of medication once control is achieved, this is done less often than recommended: 85% of changes in medication involve an increase compared to reductions in only 15%.7

These data are important because we know that high doses of ICS cause adverse effects —doses ≥500 μg/day of fluticasone propionate or equivalent could be considered high8 — and this could be avoided by using T2 inflammation biomarkers to adjust treatment.9,10 Green et al. showed that using the sputum eosinophil count for therapeutic adjustment helped reduce exacerbations in patients with moderate-severe asthma compared with following guideline recommendations, without the need for higher doses of corticosteroids. In other words, better control was achieved with the same dose, avoiding future therapeutic escalations in a significant percentage of patients.9 Another study demonstrated the discriminative ability of FENO (with a cut-off point of 30 ppb) to predict response to an increase in ICS doses in severe asthma, thus avoiding additional dosing.10

- -

Today we know that the inflammatory response is not constant in all asthmatics and that it can change over time in the same individual. The seminal study of Woodruff et al. showed that only asthmatics (with a mild form of the disease) expressing Th2 genes in bronchial epithelium cells responded to ICS.11 These data were corroborated in the SIENA study, which showed a greater clinical response to mometasone than placebo in patients with ≥2% eosinophils in sputum, but not in patients below this threshold.12 It is also well known that the response to ICS is attenuated in asthmatic patients who smoke.13 A more detailed biological characterization of patients would help clinicians avoid anti-inflammatory escalation in patients who will not respond to high doses and therefore avoid adverse effects in the absence of clinical benefit.

- -

GINA and GEMA recommend therapeutic escalation if asthma control is not achieved and provide a table of ICS equipotency, but do not take into account changes in active ingredients or devices. Yet not all drugs are the same. There are wide differences in potency and therapeutic indexes between the different ICS14 and probably also among LABAs. Despite the paucity of comparative studies between different ICS, clinical experience tells us that control can be achieved by replacing one drug with another without the need to increase the dose.

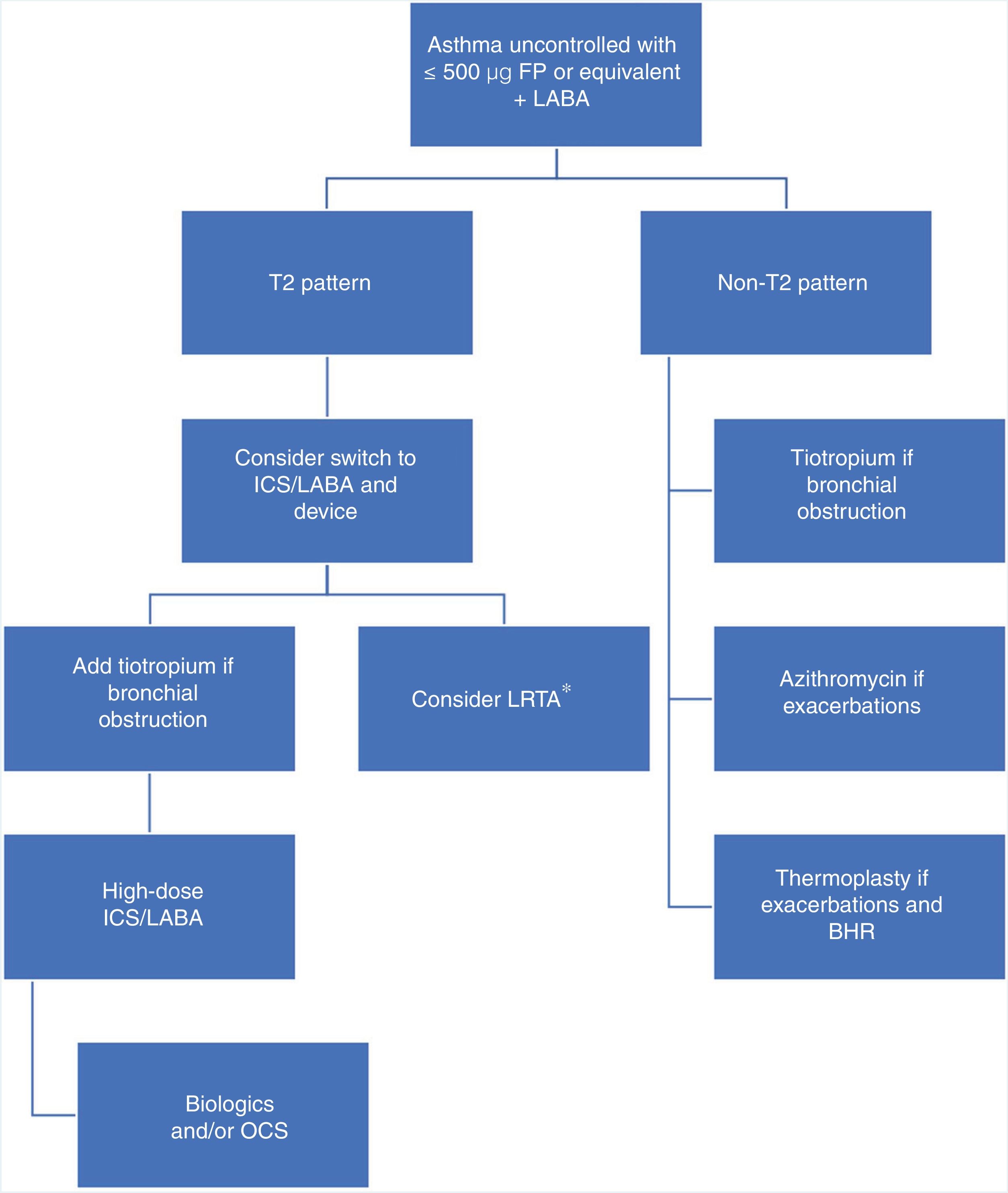

Pointing out defects in a strategic plan is relatively easy, but proposing an alternative is not so simple. We believe that the algorithm described in Fig. 1 could be appropriate, as it would take into account the underlying biological mechanism and the pharmacological differences between the different ICS, and introduce other anti-inflammatories before reaching potentially dangerous doses. This approach focuses on patients who are a greater risk of being “overtreated”, i.e., those who do not achieve control with 500 μg fluticasone propionate or equivalent. Adopting this strategy would mean that patients with a biological T2 pattern would have to be precisely identified, requiring us to use biomarkers (FENO, sputum eosinophils) that either do not have a firmly established cut-off point (FENO) or are technically difficult to determine (induced sputum). The use of FENO is more widespread and more feasible, and a cut-off point of 20−30 ppb may be a reasonable possibility according to available studies.14,15 Use of a bronchodilator such as tiotropium would be restricted to patients with bronchial obstruction or with a FEV1 value below their best personal value. To make this strategy more than a proposal, it should be compared with the approach advocated by the guidelines in a prospective, open, two-arm study.

Therapeutic algorithm for the treatment of uncontrolled asthma with high doses of inhaled corticosteroids.

BHR: bronchial hyperresponsiveness; FP: fluticasone propionate; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; LABA: long-action β-adrenergic agonists; LTRA: leukotriene receptor antagonists (*: especially indicated in patients with predominantly inflammatory changes rather than functional impairment with upper airway involvement, clinically significant allergy, or acetylsalicylic acid-exacerbated respiratory disease); OCS: oral corticosteroids; T2: inflammation mediated by T helper type 2 (Th2) cells or innate lymphoid cells type 2 (ILC2s).

- -

LPLL has received honoraria and non-financial support from NOVARTIS, grants and honoraria from ASTRA-ZENECA, honoraria and non-financial support from GSK, grants, honoraria and non-financial support from TEVA, honoraria and non-financial support from Boehringer-Ingelheim, grants and honoraria from Chiesi, honoraria from Sanofi, non-financial support from Menarini, honoraria and non-financial support from Mundipharma, and honoraria and non-financial support from Esteve.

- -

In the past three years, VP has received fees for speaking engagements at sponsored meetings of AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, MSD, and Chiesi. He has received support for attending conferences from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, and Novartis. He has been a consultant for ALK, AstraZeneca, Boehringer, MSD, Mundipharma, and Sanofi, and he has received funding and grants for research projects from various government agencies and non-profit foundations, and from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, and Menarini.

- -

SQ has organized training and consulting activities and has received speaker fees from ALK, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Leti, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and Teva.

Please cite this article as: Pérez de Llano LA, et al. Estrategia para el tratamiento del asma moderada-grave: una alternativa a la recomendada por las guías. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:243–245.