The aging of the populations in Western countries entails an increase in chronic diseases, which becomes evident with the triad of age, comorbidities, and polymedication. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease represents one of the most important causes of morbidity and mortality, with a prevalence in Spain of 10.2% in the population aged 40–80. In recent years, it has come to be defined not only as an obstructive pulmonary disease but also as a systemic disease. Some aspects stand out in its management: smoking, the main risk factor, even though avoidable, is an important health problem; very important levels of underdiagnosis and little diagnostic accuracy, with inadequate use of spirometry; chronic patient profile; exacerbations that affect survival and cause repeated hospitalizations; mobilization of numerous health-care resources; need to propose integral care (health-care education, rehabilitation, promotion of self-care and patient involvement in decision-making).

El envejecimiento de la población en los países occidentales conlleva un incremento de las enfermedades crónicas. Estas se manifiestan mediante la tríada edad, comorbilidad y polimedicación. La enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica representa una de las causas más importantes de morbimortalidad, con una prevalencia en España del 10,2% en población de 40 a 80 años. En los últimos años ha pasado a definirse no solo como una enfermedad obstructiva pulmonar sino también como una enfermedad sistémica. Algunos aspectos destacan en su manejo: el tabaquismo, principal factor de riesgo, aun siendo evitable, es un problema de salud importante; cifras de infradiagnóstico muy importantes y escasa precisión diagnóstica, con inadecuado uso de la espirometría forzada; perfil de paciente crónico; agudizaciones que afectan a la supervivencia y provocan ingresos repetidos; movilización de numerosos recursos en salud; necesidad de plantear una atención integrada (educación sanitaria, rehabilitación, promoción del autocuidado e implicación del paciente en la toma de decisiones).

With the progressive aging of the population in most developed countries, both the health-care systems and health-care professionals need to develop new strategies for the care of multi-pathological chronic patients, including a global vision and adequate coordination of treatments and services. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the most important causes of this morbidity and mortality, and its prevalence and consequences are increasing. Projected predictions indicate that in 2020 it will be the fifth cause of years of life with disability. In this article, we review the problems that are most frequently associated with treating chronic COPD patients in primary health care.

The New Paradigm of Chronic PatientsIn the early years of the 21st century, we have seen the consequences of the important demographic changes that have occurred in most developed countries. In Europe, the percentage of people over the age of 65 was 16% in the year 2000, and it is calculated to reach 27% in 2050, although in Spain this percentage may reach 35%.1 One immediate consequence is the increase in chronic diseases and the use of healthcare services as well as the increase in patients who present multiple chronic diseases. In 2006, Spaniards over the age of 65 had an average of 3 chronic problems or diseases.2

This reality has also led to the evolution of the concept of “chronic patients”, in such a way that today it does not refer to patients affected by one single disease, but instead refers those with various chronic pathologies. Age and the presence of several diseases in these patients affect their anatomy and result in fragility, which is defined as a clinical syndrome in which there is a higher risk for deteriorated functionality, associated with comorbidity and disability. Fragility is estimated to appear in 10.3% of the Spanish population over the age of 65.3

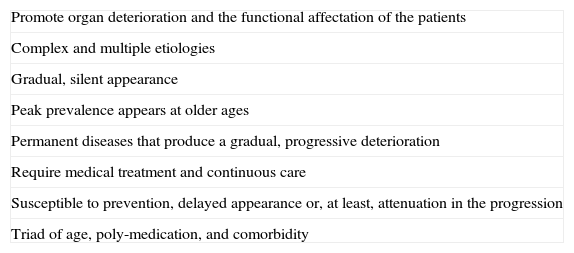

The consensus document of 2011 about care for patients with chronic diseases, written by the Spanish societies of internal medicine (SEMI) and family and community medicine (semFYC),2 summarizes the common characteristics of these diseases into seven points (Table 1). These are well-documented in current primary-care studies which once again confirm the profile of chronic patients as those of older age, with multiple pathologies and a high consumption of medication.4

Common Characteristics of Chronic Diseases.

| Promote organ deterioration and the functional affectation of the patients |

| Complex and multiple etiologies |

| Gradual, silent appearance |

| Peak prevalence appears at older ages |

| Permanent diseases that produce a gradual, progressive deterioration |

| Require medical treatment and continuous care |

| Susceptible to prevention, delayed appearance or, at least, attenuation in the progression |

| Triad of age, poly-medication, and comorbidity |

Chronic diseases are diverse, with varied combinations among them, and they affect individuals to different degrees. The individual clinical symptoms of each require its own approach, while persons affected by several entities require a complete vision and proper coordination of treatments and services. In addition, the strategy for care of new chronic patients should not be centered around the episodic care of exacerbations. Instead, they should be oriented towards proactive plans centered on the patients, arising from adequate strategic direction and with the involvement of clinicians, which integrate prevention, social health-care and the family network.5 In a recent review about chronic patient care in complex situations,6 the authors pose the need to construct integrated care scenarios based on multidimensional approaches as a shift in gear from the purely clinical treatment focus. In recent years and in various countries, different approaches have arisen that deal with the problem of chronicity. The most important is the Chronic Care Model, initiated more than 20 years ago by Wagner et al. at the MacColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation in Seattle (USA), which has given evidence of improved health results by simultaneously implementing the interventions of all the participating elements.7

The previously mentioned Spanish consensus document for caring for patients with chronic diseases is defined as an “expression of the alliance between health-care professionals and administrations with patients in order to face the changes needed in the organization of the National Health-Care System for it to meet the needs of patients with chronic diseases”.2 The document intends to raise awareness among the population, professionals and health-care administrations in order to facilitate and promote innovative initiatives that are arising in the area of micromanagement, promoting a health-care system based on integral, continuous and intersectorial care, while reinforcing the paradigm of an informed, active and committed patient who controls the reins of his/her disease.

Relevant Aspects of COPD in Chronic PatientsCOPD represents one of the most important causes of morbidity and mortality in the majority of occidental countries and, unlike what happens with cardiovascular diseases, its mortality has not diminished.8 Projections indicate that in the year 2020, COPD will be the fifth cause of years of life lost and of years of life with disability.9 The EPI-SCAN10 observational, epidemiologic, cross-sectional, and multicenter study based on a Spanish population shows a prevalence of COPD in Spain of 10.2% in the population aged 40–80,11 with a notable geographic variability in its prevalence and between sexes, which was not explainable by tobacco consumption alone.12

In recent years, the concept of the disease has gone from focusing on COPD as an obstructive pulmonary disease to defining it as a disease that is also systemic and in which the comorbidities play a transcendental role.8 The concept, which has been included in most of the consensus documents and clinical guidelines, is supported by numerous studies that show that COPD patients have a significantly higher risk of having ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes, among others, and a very high risk of premature mortality.13 COPD patients seem to die earlier due to cardiovascular causes or neoplasm, and later, if they survive, due to respiratory causes. Comorbidities should be contemplated and treated in order to improve the survival of COPD patients.14 At the same time, several studies show how COPD is one of the main comorbidities in patients with other chronic diseases, reaching for example 20%–25% of cases in heart failure.15,16 The presence of COPD increases the risk for hospitalization in other pathologies, and in hospital-discharge studies, COPD appears as the main or secondary diagnosis in between 3.5 and 8.5%.17

Just as some of the more prevalent chronic diseases that frequently accompany COPD, there are some aspects that are very important for its management which we will deal with throughout this paper:

- •

Risk factors for COPD still exist, even though they are avoidable. In this disease, smoking is still an important health problem and almost 30% of the population are active smokers.18

- •

There are important levels of underdiagnosis and little diagnostic precision,19 with limited or inadequate use of the corresponding diagnostic tests, which in this case is spirometry.

- •

The profile of chronic patients: seniors with multiple pathologies and high consumption of medications.

- •

Decompensation is a determining factor in the natural history of these diseases. In the case of COPD, exacerbation clearly affects survival and causes repeated hospitalizations.

- •

Mobilization of numerous health-care resources, both in economic expense as well as the high number of office visits.

- •

The need to consider integral care, including health education, rehabilitation, self-help, and the implication of patients in decision-making.20,21

The main national and international scientific societies, with their clinical practice consensus guidelines, have made recommendations for quality clinical practice.8,22–24 As for the diagnosis of COPD, they emphasize the detection and quantification of smoking and performing spirometry.25 The study of the lung function is of utmost importance both in the diagnosis as well as in the management of the disease, and spirometry is an essential exploration.26 Spirometry parameters have also shown a prognostic value due to their relationship with mortality.27–29 According to the quality health-care standards recommended by some experts, it is considered acceptable to correctly diagnose COPD (patient over the age of 40, exposure to a risk factor like smoking, post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC<0.7) in at least 60% of the patients labeled as COPD.30 But, more than the diagnosis, it is the evaluation of severity that has classically been established by the degree of decline in FEV1, although the incorporation of more global evaluations such as the BODE index, which also include lung function, body mass, the degree of dyspnea, and the walk test, have demonstrated better clinical predictive capacity.24

Lung function tests are necessarily generalized for the early detection and secondary prevention of the disease, the identification of all those affected and the establishment of the severity of each patient. The objective is early, adequate treatment of the disease and to prevent its unfavorable evolution by optimizing pharmacological treatment. This not only provides a clear opportunity for improving the quality care of respiratory-disease patients, but is also a challenge to promote the extensive use of spirometry while still guaranteeing its quality.31–33

Despite all this, spirometry is still underused for the diagnosis and follow-up of COPD and there is much variability in its use, both in primary care as well as hospital care. The high levels of underdiagnosis, higher than 70%, are the first consequence of this fact.12 Recent data reveal that in the primary care setting, only half of the patients with suspicion for COPD have spirometry to confirm the diagnosis.34 Nevertheless, the diagnosis of COPD in the hospital setting is also not up to par, and the underuse of spirometry is the most frequent reason for this deficiency. The audit by Pellicer et al. in 10 hospitals of the Community of Valencia showed that 54% of the patients with COPD diagnosis did not have spirometry before hospital discharge.25 The registry of spirometries in the primary care patient files is also inadequate: the study by Monteagudo et al. detected that minimal forced spirometry values (FVC, FEV1, and FEV1/FVC ratio) are not usually recorded, nor are data from bronchodilator tests, and many times the reference values used are not stated and only the FEV1 values are recorded.

In the primary care setting, which is where the majority of COPD patients are seen, quality spirometries are necessary. It is essential for the personnel performing the spirometries to be well trained, and a continuous quality control program is needed.35–37 Given the importance of the technical aspects related with correct spirometry procedure and evaluation, different national and international scientific societies have proposed recommendations and guidelines for uniform spirometry, improving the quality of the spirometric results.30,38–40 In addition, different standards have been published for preparing the techniques and work dynamics for the use of spirometers.39,41,42 However, as has been commented, the health-care reality is far from ideal, and it is currently still difficult to talk about quality care when referring to spirometry. Recently published studies still show limited accessibility to the test, limited training in the use of the techniques and difficulties for the classification of chronic respiratory diseases,25,34,43,44 as well as limited compliance with the recommendations proposed by the consensus of experts.45

The pertinence of screening in COPD with spirometry is still controversial. The recommendations vary depending on the estimated risk population,46–48 and the recommendations currently most widely used include ordering spirometry in patients older than 40 with an accumulated history of smoking and respiratory symptoms.49 Screening in asymptomatic ex-smokers or smokers raises more doubts. A study done in our setting found 20% of COPD cases in asymptomatic patients, but other authors have observed sensitively lower levels.50,51 The COPD strategy of the National Health-Care System recommends pilot studies to evaluate the efficiency of the early detection programs in smokers without respiratory symptoms.52 The impact of screening with spirometry as an effective intervention for reaching better results in smoking cessation also does not currently have conclusive evidence,46 but the results of a randomized clinical assay done recently suggests that early identification may help in specific interventions that are able to improve the smoking cessation rate.53

The consequences of the use of spirometry in the treatment of COPD are also debated in the scientific literature. There are intervention studies that prospectively evaluate the impact of the introduction of spirometry in the management of patients with COPD in primary care. These have demonstrated an improvement in the management of these patients, better approach of the differential diagnosis, increased frequency of anti-smoking or quitting advice and modification in the treatment especially in the use of corticosteroid therapy.54,55 In the study done in Catalonia by Monteagudo et al.,34 it has been observed that the use of spirometry in the follow-up of patients with COPD is associated with a higher number of visits to the family medicine practitioner and interconsultations with the pulmonologist, more registered exacerbations and complications and, although fewer hospitalizations are observed, this does not seem to translate into an improvement in the integral management of COPD patients as defined in the clinical practice guidelines (treatment compliance, rehabilitation, physiotherapy, vaccination, diet, nursing control visits), nor was it associated with a change in therapeutic approach among primary care physicians.

Comorbidities Associated With COPDComorbidity is defined as the group of alterations and disorders that can be associated with COPD for one reason or another and which, to a greater or lesser degree, have an impact on the disease, patient prognosis, and mortality.56 There may be several causes, among these age and the effects of smoking, and the exact mechanism is not well understood, although it has been proposed that it might be systemic inflammation and its mediators.57

Senior COPD patients tend to have more complications due to the greater risk of concomitant diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, lung cancer, diabetes, chronic renal disease, depression, and osteoporosis, all of which contribute to the high mortality associated with COPD. But it is precisely the comorbidities and age that have repeatedly been exclusion criteria in most research, and this has made it difficult to estimate the prognostic capacity of comorbidities in COPD. In recent years, however, several studies have paid more attention to this older age group and some conclude that COPD patients have an average of 9 comorbidities as well as a very limited understanding of their disease.58 This leads one to believe that possibly the management of the disease in this age group requires different strategies.59 And despite everything, it is still not clear whether comorbidities in COPD patients are independent processes or if COPD favors them.

Higher risk for lung cancer and cardiovascular diseases has also been reported in the initial phases of the disease. Here again, the question is raised as to whether they are merely related with the smoking risk factor, or if likewise it is the disease itself that favors other entities.

The studies are numerous and the percentages are variable, but as shown by a very recent study in primary care, more than 65% of COPD patients also have heart failure, more than one-fourth some type of psychiatric diagnosis, 17% diabetes mellitus, almost 6% osteoporosis and the same percentage have neoplasm,60 which is very significant data for describing this association of pathologies.

Briefly, we will review some of the most frequent comorbidities.

COPD and Heart FailureThis well-known association was the subject of an excellent publication in this journal,61 which reviewed data such as the risk for developing heart failure (HF) in COPD patients (4.5 times higher than in people without the disease), the contribution of biological markers and the correct interpretation of the diagnostic tests for both entities (echocardiography and spirometry), and the influence of COPD treatment in the evolution of HF and vice versa. Some studies of hospitalized COPD patients show that HF is the most frequently found comorbidity in patients who do not survive.62 In primary care, some studies quantify the presence of COPD in more than 25% of the patients diagnosed with HF.4 Thus, COPD is frequently associated with HF and is also a prognostic indicator of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with HF. The difficulty for the differential diagnosis between both entities, especially in acute situations, is a clinical reality that should not be obviated.

COPD and Ischemic Heart DiseaseA strong association has been demonstrated between COPD and coronary disease. Ischemic heart disease, not HF, is the main cause of death among patients with COPD.61 The relationship between both entities has always been attributed to tobacco use, but there is more and more evidence concerning the role of systemic inflammation in COPD, evaluated by means of measuring the levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and with the response of these to treatment with statins. Regarding the treatment of both entities, the most recent developments are related with the safe use of cardioselective beta blockers when they are necessary for HF, as long as they are well tolerated and are used with gradual increments.63 A mortality rate of 21% due to ischemic heart disease has been reported in patients with COPD, compared with 9% in those who do not have COPD.64

COPD and Lung CancerBeyond the causal relationship with tobacco, several studies have demonstrated that COPD is an independent risk factor for lung cancer and that this cancer is between 2 and 5 times more frequent in smokers with COPD than in smokers without COPD; an inverse relationship has been observed between the degree of obstruction and the risk for developing cancer.65 In addition, it is an important cause for mortality in COPD; a meta-analysis of some years ago showed that the risk is related with the degree of obstruction and it is higher in women.66

COPD and Alteration of the Metabolism of GlucoseThe relationship between the two entities is determined by the high prevalence of diabetes in COPD patients (up to 17%), the increased risk for hyperglycemia with the use of systemic corticosteroids in COPD, and the poorer evolution of the exacerbations observed among COPD patients who also have diabetes, as well as a more unfavorable course of the disease.56,67

COPD and Psychiatric AlterationsThe prevalence of anxiety disorders and depression is higher among patients with COPD than in the general population, and these conditions seem to increase the mortality of the pulmonary disease. The associated variables may be dyspnea and comorbidity.

COPD and OsteoporosisThe prevalence of osteoporosis can be very variable, but in several studies it is shown to be higher in COPD than in healthy people or in those with other respiratory diseases. This association can be related with age, smoking, malnutrition, limited physical activity, the use of corticosteroids or vitamin D deficiency. Nevertheless, it seems that, even when isolated from these factors, the prevalence is higher in COPD, which has raised suspicions and led to the study of its relationship with the systemic inflammatory component of COPD.67

Exacerbation and HospitalizationsOne of the characteristics of COPD is the existence of exacerbations. These are periods of clinical instability that occasionally require hospitalization. They are currently considered key elements in the natural history of COPD, and recent studies emphasize the strong impact of exacerbations on the state of health of patients, their extrapulmonary repercussions and influence on the progression and prognosis of the disease.68–71 In addition, they generate an increased health-care load, high health-care costs, as well as a decline in the mid- and long-term quality of life69,72 and increased patient mortality.68 The definition of exacerbation has been the subject of discussion for decades. The GOLD guidelines8 states, “An exacerbation of COPD is defined as an event in the natural course of the disease characterized by a change in the patient's baseline dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum that is beyond normal day-to-day variations, is acute in onset, and may warrant a change in regular medication in a patient with underlying COPD”. This definition presents some limitations due to the difference in the perception of the symptoms and the possible confusion with recurring diseases (pneumonia, IC, pneumothorax, etc.). Some authors have suggested incorporating the inflammatory concept in the definition73 due to the fact that during exacerbation there is an amplification of the inflammatory response that is both local74 as well as systemic.75 The latter could explain some of the extrapulmonary manifestations, especially cardiovascular ones. The repercussions of the exacerbations on the individual depends on different aspects, among which are the baseline state and particularly the severity and duration of the exacerbations.76

COPD patients are estimated to have an average of between 1 and 4 annual exacerbations.77 There is great inter-individual variability, meaning that in some cases there are hardly any exacerbations, while in others they are repetitive. Thus, and due to the evidence that the severity and the prognosis are not only related with FEV1, as commented in this review, in recent years there have been many studies about the different COPD phenotypes (groups of patients who share a specific characteristic or combinations of characteristics with different clinical outcomes).78 In this context, a specific patient group has been described that is characterized by a susceptibility for exacerbations and a high morbidity and mortality, which some authors identify as the “exacerbator phenotype”.79,80

In our setting, it is estimated that exacerbations generate 10%–12% of the consultations in primary care, between 1 and 2% of all the visits to the emergency room and around 10% of hospitalizations.81 COPD is the third most frequent cause of hospitalization (2.5%), with a mean stay of 8–10 days.82,83 The expenses produced by this disease reach 2% of the annual budget of the Ministry of Health.84 It is calculated that a COPD patient generates an average direct health-care expenditure of 1876 Euros/year; a large part of this cost is due to hospitalization (43.8%), followed by the cost of medication (40.8%) to control the disease.85 Almost 60% of the total cost of COPD is caused by exacerbations.86 A study done in Catalonia with a sample of 174,000 adults found that the predictive factors for re-hospitalization within 6 months were: male sex, age over 65, diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes, heart failure, emphysema or COPD, using more than 4 medications and having had previous hospitalizations.87

There is also a well-known high rate of re-hospitalizations, which reflects the complexity of advanced pathologies, comorbidity, fragility and also the relationship between the different levels of health-care, all of which lead to more than one-third of the patients being re-hospitalized within one year of a hospitalization, with a mean discharge of 5 months.68,88 In a study by Martín et al. in patients over the age of 74 in Madrid, it is stated that, given these facts, the integration of clinical-administrative data from primary care and hospitals could improve the capability to identify factors associated with a greater risk for re-hospitalization, which could be used to develop strategies.89

Quality of Life and SymptomsThe concept of quality of life can be defined as the difference between what one wants to do and what one can do90 or, in other words, the state of health perceived by the patient. It is the result of the interaction of many physiological and psychological factors and its alteration is mainly a consequence of the symptoms, emotional disorders and physical limitations as well as the social role caused by the disease.91 The measurement of the state of health in COPD has been generalized since the paper by Jones et al.90

There are 2 types of quality-of-life questionnaires: generic and specific. The generic ones have been designed to compare patient populations, and have demonstrated to be useful as discriminative tools among them, being insensitive to the changes in the state of health.92 The specific COPD surveys, among these being Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ)93,94 are useful tools for evaluating the interventions in these patients. These are used to evaluate oxygen therapy,95 pulmonary rehabilitation,96,97 re-hospitalizations98 and the exacerbations of COPD patients.99 Likewise, they have been incorporated in all the new COPD drug trials by European demand.91

Both questionnaires have been adapted to Spanish: CRQ was adapted by Güell et al.100 and the SGRQ by Ferrer et al.101 The CRQ is divided into 4 sections or health dimensions: dyspnea, fatigue, emotional function and disease control; the highest scores indicate a better quality of life. There is a self-administered version102 of the questionnaire. A change of 0.5 units in the score is considered a clinically significant difference.103 The SGRQ is self-administered and is divided into 3 subscales: symptoms, activity (activities that cause or are limited by dyspnea) and impact (social function and psychological disorders caused by the respiratory disease). The patient needs 10–15min to complete the survey. Some items of the questionnaire are answered with a scale of 5 responses, while others are dichotomic (yes/no). Because the answers are weighted, the calculation of the score is a rather complex procedure, and a computer program is needed. The score for each of the dimensions and the total score range between 0 and 100. In this questionnaire, the highest scores indicate a poorer quality of life. In this case, a change of 4 units in the score is considered a clinically significant difference.

As for the follow-up of the patients, it is important to underline that the practice should be based on a control of the symptoms, basically dyspnea, which has been shown to have a clear relationship with patient quality of life.104 In order to measure dyspnea objectively, it is useful to use the modified Medical Research Council scale.105

Health-Care Education and Patient InvolvementCOPD patients require specific know-how about the concepts about their disease, as well as skills in order to follow their regular treatment and to take immediate steps in situations of deterioration. Teaching patients these concepts and skills is what is known as patient “health-care education” and its goal is to improve therapeutic compliance.106 Educational programs aimed at smoking cessation, the correct application of inhalation techniques and the early identification of exacerbations, together with vaccination campaigns, have demonstrated their great impact in the progression of the disease.107 These interventions are fundamental and should be considered the first therapeutic step in COPD treatment. An understanding of the disease and its treatment is essential, as with it the patients can modify their behavior, improve their degree of satisfaction and consequently improve their quality of life, while reducing the cost of care. In order to reach the best possible results, it is also necessary to improve the health-care skills and abilities of patient caretakers.108 The authors of the Spanish COPD Guidelines (Guía Española de la EPOC—GESEPOC)67 highlight the crucial role of self-care in improving the results of the health-care process.

“Self-care” is a term applied to a patient education program aimed at teaching the aptitudes necessary for carrying out specific medical regimes in COPD. It guides necessary changes in health conduct and provides patients with emotional support to control their disease and to live a functional life.107 In asthma, patient self-care and education programs have had proven success, but in COPD the data of the review done by Monninkhof109 have not been conclusive in order to propose recommendations. Several studies have been published and Effing et al. did a review for Cochrane with the purpose of evaluating the influence of the self-care programs on health results and the use of health-care in COPD.110 While concluding, the authors described a decline in hospitalizations in patients who had taken part in the education program and they detect positive effects in the use of health-care services: a reduction in doctor and nursing staff visits and a small but significant reduction in the Borg scale dyspnea score. There is also an observed positive tendency in quality of life. However, due to the heterogeneity of the interventions, study populations, follow-up period and result measures, the data are still not sufficient to formulate clear recommendations for the shape and the content of the education programs in self-care for COPD patients. Recently, there have been important changes in COPD management that have modified the focus of the disease towards personalized, predictive, preventive care with the participation of the patient in the health process and preventive actions.111 Some strategies for improving these skills and abilities may include personalized plans of action, “expert patients” or group visits.112,113

In the next few years, the concept of “expert patient” may be of great help, as is already being observed in the start-up of the “Expert Patient Program” by the Catalonian Health Institute in primary care, in place since 2006. The evaluation of the program is done with surveys that analyze habits, lifestyles, self-care, dyspnea scale, doctors and nursing visits, exacerbations and hospitalization. The preliminary results include an observed tendency towards a reduction in hospitalizations, a reduction in primary care visits and the maintained improvement in the level of comprehension, with the acquisition of more resources given the disease and treatment.114,115 The autonomy of the patient and his/her participation in the decision-making process are today a subject of debate because there are not many studies that demonstrate their effectiveness or adequacy for every patient or every moment of the disease.116

The fight against smoking is the cornerstone of COPD patient health care. Smoking cessation is the most effective individual intervention for reducing the risk of developing the disease and for delaying its progression.8 It is well-known that intensive anti-smoking strategies increase the probability that the smoking cessation will last,8 and the same is true for the new laws that regulate smoking prohibition in public places. At the same time, a review about tobacco and publicity shows how the incidence and impact of tobacco advertising are high and use culturally and socially adapted messages.117 Many studies have observed that when COPD patients stop smoking, they experience a notable improvement in respiratory symptoms and the decline in FEV1 slows down.118 Despite this, the IBERPOC study verified that almost 70% of people with mild COPD still smoked, and that many had not even thought about quitting.119 One recent study done in the Community of Madrid analyzed the attitude towards tobacco of patients with chronic pulmonary diseases in advanced phases, mainly COPD, who were being treated with home oxygen therapy. Said study observed that a high proportion of patients continued to smoke (mostly males and younger patients), and it was striking that 17% of the smokers stated that they had not been warned about the high degree of physical dependence on nicotine or about the need to quit smoking.120 These results are parallel to some found in studies of patients with cardiovascular risk factors, among whom the percentage of active smokers remained stable over time.121

Another key point of health education is teaching the correct inhalation technique for the administration of medication, as there is much evidence that an optimal benefit is not being obtained from inhaled therapies, mainly due to the incorrect use of inhalers.106 Therefore, it is essential to review the patient treatment and evaluate the inhalation technique at each office visit. Health-care professionals must teach patients the inhalation technique: explain the technique for using the device, use practical demonstrations and use devices without medication in order to ensure correct handling, make periodical evaluations of the errors, explain maintenance, secondary effects, and how to avoid them.122

In 2003, the WHO defined the term adherence as “the degree to which the person's behavior (taking medication, following a diet, or modifying lifestyle) corresponds with the agreed recommendations from a health care provider”.123 In developed countries, the rates of treatment adherence in chronic diseases are situated around 50%. It is a complex process that is influenced by inter-related factors and are: the patient (level of education, personality, beliefs), the drug (adverse effects, cost, active ingredient), the disease (chronic diseases have higher levels of incompliance), and the health-care professional (time, difficulties in communication, etc.).124 Therapeutic incompliance is especially frequent in chronic diseases, when the patient is well-controlled, in seniors and in patients that have various treatments prescribed.125,126 Its consequences are the reduction in the positive health results and increased cost. Strategies for improvement include simplifying the prescription regime, behavioral techniques (reminders or calendars), education or social support (home assistance) and support from the health-care professional (communication techniques, behavioral techniques, behavioral strategies). One study in primary care with 220 patients demonstrated that, when an individualized system of medication dosage was used, patient therapeutic compliance improved.127 All these aspects are seen in inhaled COPD treatment, in which adherence with the inhalation technique is the basis for success in patient control; however, the studies have not centered around confirming this point. Takemura et al. studied the relationship between the adherence with the inhalation technique and quality of life. They concluded that the repeated instruction of the inhalation techniques can contribute to adherence to therapeutic regimes, which at the same time is related with a better state of health in COPD.128

As for COPD patients, the perceptive component (knowing the opinion of affected persons, their preoccupations and preferences), therapeutic adherence and compliance have recently gained protagonism.111 On many occasions, this perception is not reflected in the functional markers used to monitor the disease. Therefore, tools have been designed to obtain this information, whether through quality-of-life questionnaires or rather with so-called POR (patient outcome reports). These are suggested by the COPD strategy of the National Health System52 as they obtain information on a dimension of the disease from the patient without the need for functional testing. Other dimensions are also being studied, such as the repercussions in physical activity, emotional state and the social or family impact.

COPD InitiativesGiven the complexity of chronic diseases, and of COPD in particular, many initiatives have been developed to improve understanding, circuits and strategic planning. Presented below are some of these experiences, although not as an exhaustive review, but instead with the intention of presenting illustrative examples.

Clinical GuidelinesThese are directives for clinicians and their aim is to unify criteria and compile the most recent evidence. In recent years, there has been a proliferation of COPD guidelines and the most recent revisions or updates all include aspects related with the systemic effects of the disease and comorbidity. In this sense, and in the context of the management of COPD patients as chronic patients, we highlight from among these:

World-WideThe GOLD8 and NICE23 guidelines, as well as those of the American Thoracic Society together with the European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS).24

NationalThe SEPAR-ALAT22 guidelines, the semFYC-SEPAR49 clinical practice guidelines and the recent GESEPOC initiative.67 The latter is headed by SEPAR, is interdisciplinary in nature in accordance with the COPD Strategy of the Ministry of Health, and has 3 lines of action: scientific-medical, which is in charge of creative guidelines directed at the diagnosis and treatment of the disease adapted to all the collectives involved; patients, in order to deal with the worries and needs of people with COPD and with their active participation; diffusion-communication, in charge of preparing informational material, press communications and relations with social and economic administrators in order to communicate the reality of COPD and the people who are affected by it.

Local GuidelinesThe CIM, which is the interdisciplinary COPD consensus in Catalonia,129 is a consensus initiative among scientific societies.

Organization GuidelinesThe clinical practice guidelines of the Institut Català de la Salut130 were created by professionals of the same organization from different disciplines and health-care settings, which also has available an integrated computerized version for primary care patient files.

Institutional InitiativesNational Conference for Treating Patients With Chronic DiseasesPromoted by semFYC and SEMI, this is a meeting point for health-care authorities, clinicians, directors and patients. In January 2010, this conference approved the previously mentioned consensus document2 and promoted the state of integral plans for patients with chronic diseases in the autonomous communities (provinces), based on comprehensiveness, continuity of care and intersectoral collaboration.131

COPD Strategy of the National Health SystemThis was developed by the Ministry of Health in 2009,52 given the situation of a disease that causes great mortality and health-care expenditure, while being linked to an avoidable risk factor: smoking. It is striking that at that time only 7 Autonomous Communities had developed specific actions based on consensus between the primary care and specialized care levels directed at the integral management of COPD. The COPD Strategy defines the following strategic lines for reaching the greatest efficacy and quality in the management and treatment of this pathology in the health-care services, which should be a guideline for initiatives at any level: early prevention and detection, chronic patient care, patient care during exacerbation, palliative care, training of professionals and research.

Respiratory Disease DirectivesPromoted by the Catalonian Department of Health, the Respiratory Disease Directives intend to define prevention strategies and fight against these diseases, as well as define the model of care and organization of the health-care services based on each reality, while making advances in effective and quality care and rehabilitation.132

Territorial Care ProcessThe Procés MPOC133 is an organizational model of territorial clinical management in an area of Barcelona, based on the collaboration of all the professionals involved from different specialties and health-care settings who participate in COPD patient treatment. It establishes a series of multidisciplinary interventions that integrate the different aspects of the disease and coordinate the health-care levels that are implicated.

FundingNo funding was received.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare having no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Llauger Roselló MA, et al. Atención a la EPOC en el abordaje al paciente crónico en atención primaria. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:561–70.