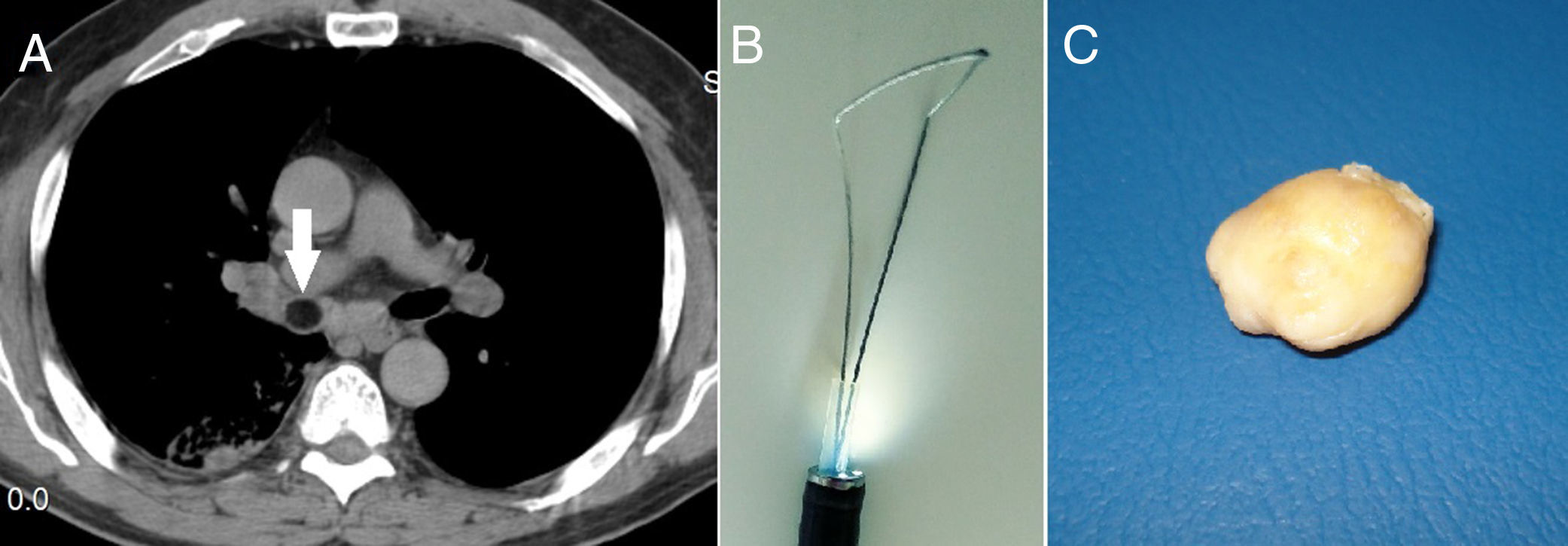

Endobronchial lipomas are rare benign tumors which are amenable to endoscopic management both for diagnosis and treatment. Excluding those cases that merits surgical treatment, endoscopic mechanical debulking in conjunction with other techniques actually are the preferred method of treatment as it results in complete resection and preserve lung parenchyma.1 These tumors are poorly vascularized and patients rarely present with hemoptysis, and if that is the case, it has been mainly attributed to post obstructive pneumonia or bronchiectasis rather than the tumor itself.2 With all of this in mind, we recently decided to resect a previously histologically confirmed endobronchial pedunculated lipoma which obstructs the intermediary bronchus (Fig. 1A) from a 69-year old never smoker man who has a history of recurrent right lower pneumonia and with the aid of a cold snare device (Fig. 1B) intended for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (Cook Medical). In a similar way as described by other authors using a polypectomy electric snare,3 we grasp the endobronchial lipoma with the snare introduced in the 2.6mm working channel of an Olympus LF-TP flexible fiberscope which in turn was placed through the rigid bronchoscope to the right main bronchus. The open snare was carefully positioned around the lipoma taking care to grasp its pedicle. Once the snare has been closed, a clean cut was obtained under the large part of the lipoma with minimal blood loss. The resected lipoma and the scarce residual lipomatous tissue were finally removed with a large forceps (Fig. 1C).

The successful use of an electrosurgical snare to resect endobronchial lipoma has already been described by other authors,3–5 but actually there are no reports using a cold snare. Our method requires a precise diagnosis since other endobronchial lipomatous tumors that are radiologically and macroscopically very similar with lipomas are more amenable for bleeding complication.2 Already corroborated the correct histopathological diagnosis, a second endoscopic procedure will be required to resect the lipoma. Our diagnosis of endobronchial lipoma was performed during a first rigid bronchoscopy and by means of large excisional biopsy that reasonably excluded other pathologies. During the second endoscopy, the gelatinous consistency of the tissue did not allow us to complete the removal of the large tumor remnant with only forceps. Endobronchial lipomas generally initiate in the submucosa and histological analysis of the lesions reveals lobes of mature fat cells, either partially or totally surrounded by a fibrous capsule without a prominent vasculature. This is the reason why in situations where conventional bronchoscopic ablative therapies are not available, an endobronchial neoplasia compatible with a lipoma could be resected with an improvised instrumentation with minimal risk of bleeding.

If there is a risk of long-term recurrence of this tumor using endoscopic debulking techniques, this is an issue yet to be defined by researchers, but for the moment our main goal was to avoid recurrent post-obstructive infections and their sequelae.