Tuberculosis (TB) control is based on early case detection, initiation and completion of treatment, effective contact tracing, and the appropriate diagnosis and treatment of tuberculous infection in people at risk of developing disease.1 The longer a patient with pulmonary TB remains undiagnosed or untreated, the greater the chances of disease transmission and epidemic outbreaks.2,3

The main objectives of this study were to analyze the diagnostic delay of TB in Spain, to determine the associated factors, and to determine to what extent delays are attributable to the patient and to the health system.An observational, prospective, multicenter study was conducted in Spain in patients diagnosed with TB during the period 2015–2017 and listed in the registry of the Integrated Tuberculosis Research Program (PII-TB) of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR). “Delay attributable to the patient” (DP) was defined as the time from the onset of symptoms to the request for health care by the patient; “delay attributable to the health system” (DS) was the time from the request for assistance to the start of treatment; and “overall diagnostic delay” (OD) was calculated as DP plus DS.4 The median diagnostic delay was calculated for each group. Variables associated in the univariate analysis with p<0.15 were included in a multivariate model, and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated, p<0.05 being considered significant.

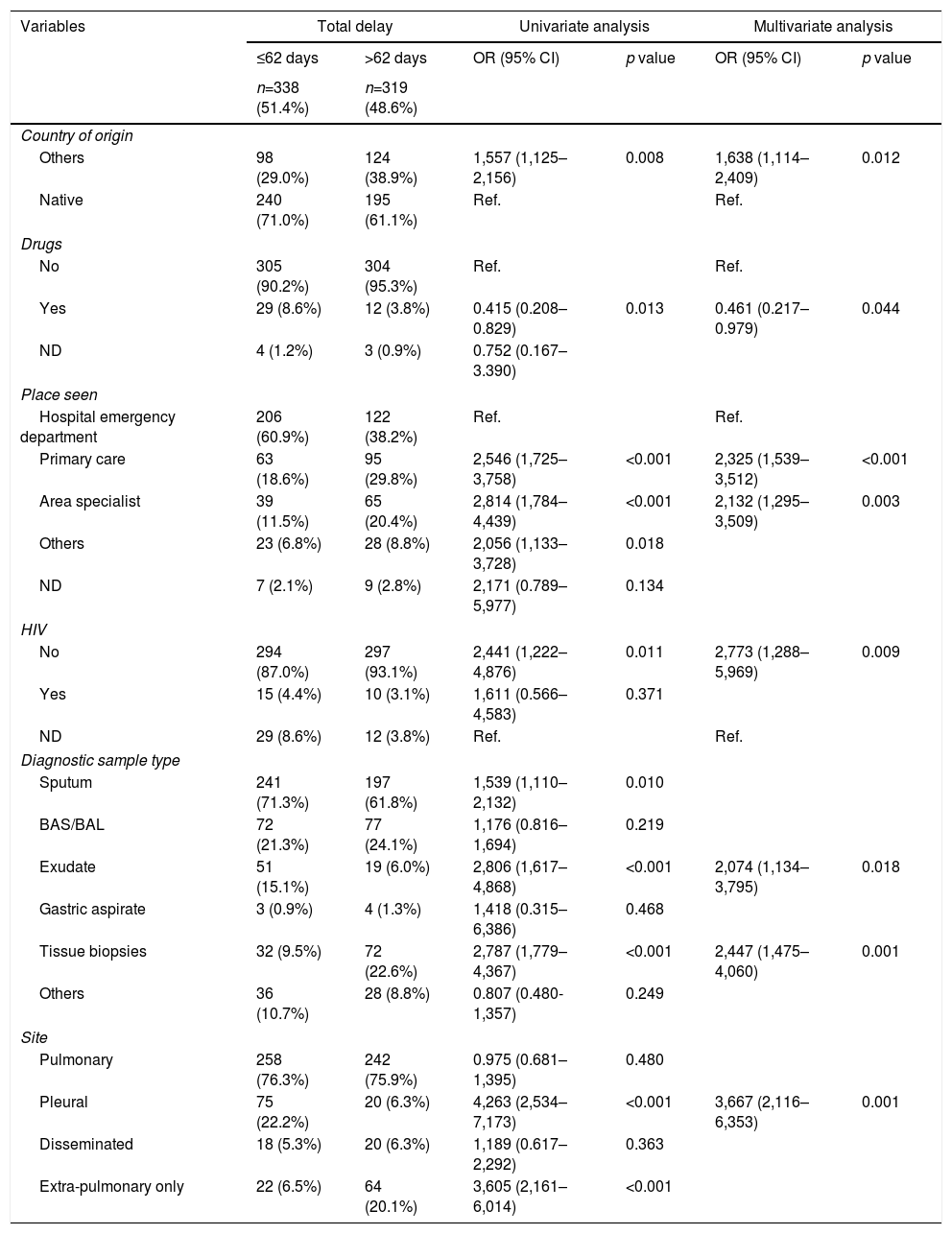

Overall, 657 cases were analyzed (52% bacilliferous). Median OD for all cases was 62 days and 61 days for bacilliferous cases. DP was 29 days and DS was 11 days. The OD was attributed to the patient in 82.6% cases and to the system in 17.4%. Factors associated with diagnostic delay, defined as greater than the median delay relative to the study variables, are described in Table 1.

Factors associated with diagnostic delay in all study cases. Univariate and multivariate analysis of the study variables.

| Variables | Total delay | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤62 days | >62 days | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| n=338 (51.4%) | n=319 (48.6%) | |||||

| Country of origin | ||||||

| Others | 98 (29.0%) | 124 (38.9%) | 1,557 (1,125–2,156) | 0.008 | 1,638 (1,114–2,409) | 0.012 |

| Native | 240 (71.0%) | 195 (61.1%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Drugs | ||||||

| No | 305 (90.2%) | 304 (95.3%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 29 (8.6%) | 12 (3.8%) | 0.415 (0.208–0.829) | 0.013 | 0.461 (0.217–0.979) | 0.044 |

| ND | 4 (1.2%) | 3 (0.9%) | 0.752 (0.167–3.390) | |||

| Place seen | ||||||

| Hospital emergency department | 206 (60.9%) | 122 (38.2%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Primary care | 63 (18.6%) | 95 (29.8%) | 2,546 (1,725–3,758) | <0.001 | 2,325 (1,539–3,512) | <0.001 |

| Area specialist | 39 (11.5%) | 65 (20.4%) | 2,814 (1,784–4,439) | <0.001 | 2,132 (1,295–3,509) | 0.003 |

| Others | 23 (6.8%) | 28 (8.8%) | 2,056 (1,133–3,728) | 0.018 | ||

| ND | 7 (2.1%) | 9 (2.8%) | 2,171 (0.789–5,977) | 0.134 | ||

| HIV | ||||||

| No | 294 (87.0%) | 297 (93.1%) | 2,441 (1,222–4,876) | 0.011 | 2,773 (1,288–5,969) | 0.009 |

| Yes | 15 (4.4%) | 10 (3.1%) | 1,611 (0.566–4,583) | 0.371 | ||

| ND | 29 (8.6%) | 12 (3.8%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Diagnostic sample type | ||||||

| Sputum | 241 (71.3%) | 197 (61.8%) | 1,539 (1,110–2,132) | 0.010 | ||

| BAS/BAL | 72 (21.3%) | 77 (24.1%) | 1,176 (0.816–1,694) | 0.219 | ||

| Exudate | 51 (15.1%) | 19 (6.0%) | 2,806 (1,617–4,868) | <0.001 | 2,074 (1,134–3,795) | 0.018 |

| Gastric aspirate | 3 (0.9%) | 4 (1.3%) | 1,418 (0.315–6,386) | 0.468 | ||

| Tissue biopsies | 32 (9.5%) | 72 (22.6%) | 2,787 (1,779–4,367) | <0.001 | 2,447 (1,475–4,060) | 0.001 |

| Others | 36 (10.7%) | 28 (8.8%) | 0.807 (0.480-1,357) | 0.249 | ||

| Site | ||||||

| Pulmonary | 258 (76.3%) | 242 (75.9%) | 0.975 (0.681–1,395) | 0.480 | ||

| Pleural | 75 (22.2%) | 20 (6.3%) | 4,263 (2,534–7,173) | <0.001 | 3,667 (2,116–6,353) | 0.001 |

| Disseminated | 18 (5.3%) | 20 (6.3%) | 1,189 (0.617–2,292) | 0.363 | ||

| Extra-pulmonary only | 22 (6.5%) | 64 (20.1%) | 3,605 (2,161–6,014) | <0.001 | ||

The greater delay observed among foreign patients is probably due to a reluctance to consult the health system because of language barriers, or cultural, social or legal factors5; similar results were obtained in Italy and Portugal.6,7

The increased delay in the outpatient system compared to the emergency department may be due to the decreased incidence of TB in recent years,8 because physicians may be less likely to consider this diagnosis. It may also reflect better access to emergency departments.

Drug use appears as a factor associated with less delay, as there may be higher diagnostic suspicion in this group.9

Our results were similar to others published not only in Spain,10,11 but also in neighboring countries.12,13 The greater delay when exudates and biopsies are used for diagnosis, as in pleural tuberculosis, is noteworthy. These times to diagnosis must be reduced by implementing new diagnostic techniques.14,15

We conclude that the diagnostic delay of TB in Spain is still prolonged, while the greater part of the delay is attributable to the patient. Interventions to correct this situation must be based on disseminating knowledge about the disease, both among the general population and among health professionals, and improving access to health services.

FundingThis study was funded with a Research Grant from the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR)134/2014.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

The authors are particularly grateful for the effort and time of all researchers who collaborated in the PIITB Research Group.

A. Bustamante (Hospital Sierrallana, Torrelavega); E. Carrió (Centro Asistencial Dr. Emili Mira I López, Santa Coloma de Gramanet); X. Casas (Serveis Clínics, Barcelona); A. Cecilio (Hospital Universitario Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza); L. Domínguez (Hospital Universitario de Ceuta, Ceuta); M. Domínguez (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona); S. Dorronsoro (Hospital de Zumárraga, Zumárraga); J. Esteban (Hospital de Cruces, Barakaldo); M. García (Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón); F.J. Garros (Hospital Santa Marina, Bilbao); P. Gijón (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid); Y. González (Serveis Clínics, Barcelona); J.A. Gullón (Hospital San Agustín, Avilés); I. Jiménez (Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra – B, Pamplona); M. Jiménez (Hospital Universitario de Donostia, Donostia); I. López (Hospital Universitario de Cruces, Barakaldo); M. Lumbierres (Serveis Clínics TDO, Lérida); M. Marín (Hospital General de Castellón, Castellón); J.P. Millet (Serveis Clínics, Barcelona); I. Molina (Serveis Clínics, Barcelona); J. Ortiz (Hospital El Bierzo, Ponferrada); E. Pérez (Hospital SAS de Jérez, Jérez de la Frontera); V. Pomar (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona); R. Rabuñal (Hospital Lucus Augusti, Lugo); J. Rodríguez (Hospital San Agustín, Avilés); M.J. Ruiz (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid); F. Sánchez (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona); I. Santamaría (Hospital Txagorritxu, Vitoria); M. Santín (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat); F. Sanz (Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); A. Soriano (Hospital Vall D’Hebrón, Barcelona); I. Suárez (Hospital Universitario de Canarias, La Laguna); J. Ugedo (Complejo Hospitalario San Millán-San Pedro, Logroño); J.L. Vidal (Complejo Hospitalario La Paz-Cantoblanco-Carlos III, Madrid).

Please cite this article as: Seminario A, Anibarro L, Sabriá J, García-Clemente MM, Sánchez-Montalván A, Medina JF, et al. Estudio del retraso diagnóstico de la tuberculosis en España. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:440–442.