We read with great interest the well-written letter to the editor by Ronda et al.,1 who reported the case of an 84-year-old man presenting with severe involvement by Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated consolidation in the left upper lobe, with areas of cavitation with irregular walls. Cytological analysis of bronchial aspirate showed S. stercoralis larvae.

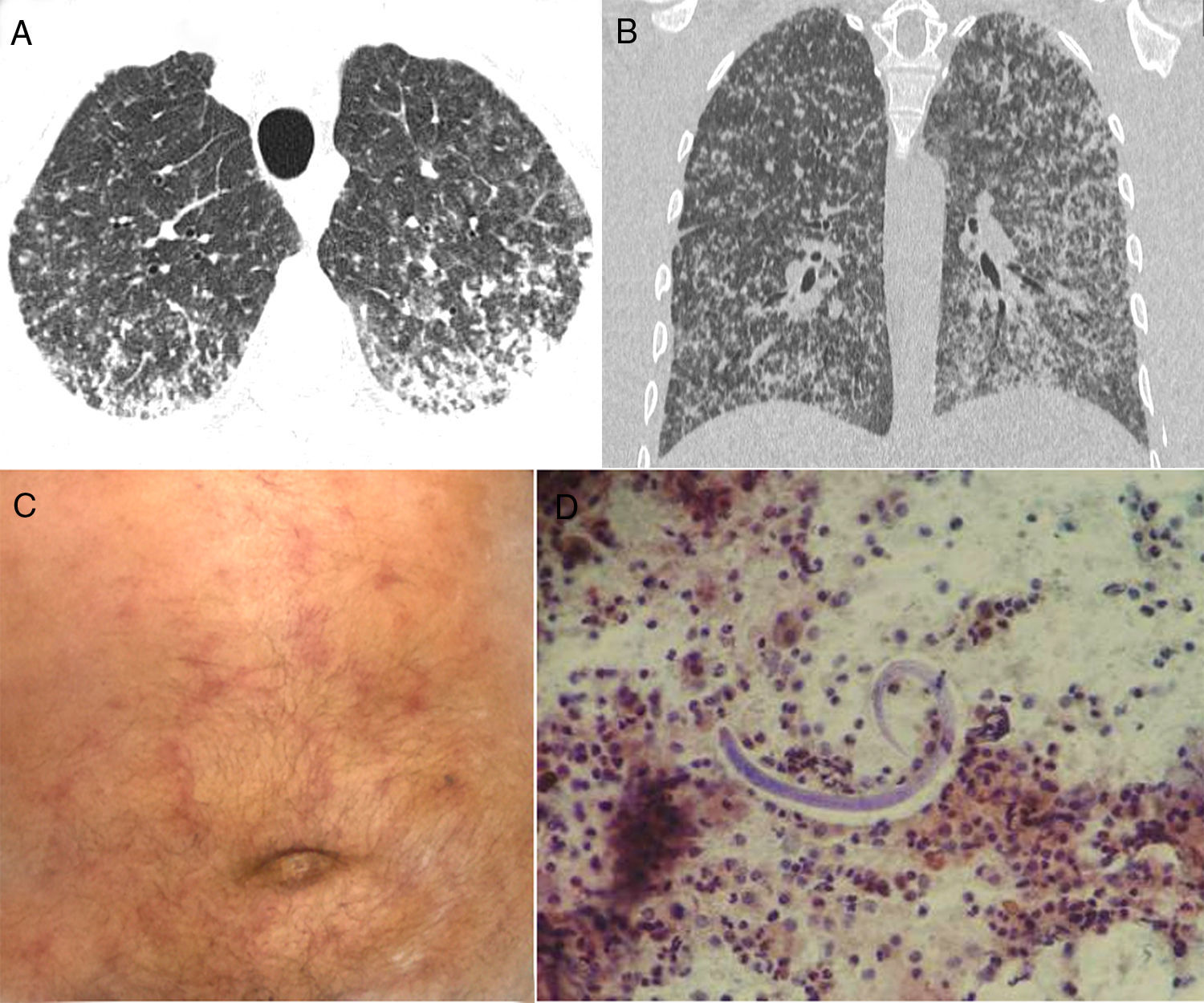

We would like to report another case of S. stercoralis hyperinfection, with a very uncommon CT pattern: micronodular dissemination. A 73-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a 2-week history of productive cough, weakness, fever, and progressive dyspnea. He had lost 8kg weight in 2 months, but had no other complaint. His oxygen saturation in room air was 96%. Laboratory findings were normal. Chest CT revealed numerous bilateral small nodules, with some coalescence in the posterior and lower lung regions (Fig. 1A, B). On day 8, he developed a maculopapular (purpuric) rash (Fig. 1C). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) performed during flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed the presence of S. stercoralis larvae (Fig. 1D). BAL findings for bacteria, fungus, and acid-fast bacteria were negative. Blood cultures were also negative. A stool sample demonstrated numerous larvae, as well as a few adult organisms. The patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), but positive for human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) I/II quantitative antibodies. A diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome was made, and treatment with ivermectin and albendazole was started.

Axial (A) and coronal (B) reformatted CT images show numerous bilateral small nodules, with some confluence in the posterior and lower lung regions. (C) Physical examination demonstrated a purpuric serpiginous rash on the patient's abdomen. (D) Bronchoalveolar lavage revealed the presence of Strongyloides stercoralis filariform larvae.

Strongyloidiasis, an infection caused by the nematode S. stercoralis, is prevalent in tropical and subtropical countries.2–4 In the setting of severe immunosuppression, the worm may disseminate, causing severe life-threatening syndromes such as hyperinfection and dissemination, showing massive infection.2 These syndromes are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.2 The clinical diagnosis is often delayed because the clinical and radiographic findings are nonspecific. The most important risk factor for the development of Strongyloides infection is residence in or visit to an endemic area.5S. stercoralis hyperinfection is generally fatal, as it is normally associated with immunosuppression, either iatrogenic (e.g., caused by systemic corticosteroid use) or to underlying illness (e.g., HIV infection, HTLV-1 carriage, or organ transplantation).2,5

Hyperinfection syndromes manifest clinically in a nonspecific manner, with gastrointestinal and pulmonary symptoms being the most common findings.2 The pathognomonic rash of Strongyloides infection is a serpiginous and urticarial petechial purpuric eruption over the abdomen and proximal thigh.4 Pulmonary symptoms and signs consistent with adult respiratory distress syndrome or intra-alveolar hemorrhage may be seen. Radiographic changes may include nodular, reticular, and airspace opacities, with distribution ranging from multifocal to lobar.3 Blood eosinophilia is seen in more than 75% of patients with chronic Strongyloides infection, but may be absent in immunocompromised patients with hyperinfection syndrome.2,3,5 Detection of a large number of larvae in stool and/or BAL fluid or sputum is a hallmark of hyperinfection.5 Therefore, the diagnosis rests mainly on the recognition of the organism's morphology in pathology specimens.2 In conclusion, in endemic areas, Strongyloides hyperinfection should be included in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary miliary lesions.

Please cite this article as: Hochhegger B, Zanetti G, Marchiori E. Infección por Strongyloides stercoralis con patrón miliar difuso. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:352–353.