Mycobacterium szulgai is slow-growing, rarely isolated environmental non-tuberculous mycobacterium (NTM).1 It accounted for less than 0.2% of isolated strains in a study of over 36000 NTM samples from 14 countries, including Spain.2 Like other NTM, it can be present in dust, soil, water, plants, and animals.3 Isolation from the respiratory tree does not always imply disease, so the American Thoracic Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have produced a series of diagnostic criteria in an attempt to establish the pathogenic role of this and other NTM when isolated from biological samples.4

We report the case of a 49-year-old woman, employed as a cleaner, smoker of 35 pack-years, chronic alcoholic with moderate COPD, who was transferred by ambulance to the emergency department in coma (Glasgow scale 3), shock (BP 50/30mmHg) and respiratory failure (SO2 75% with FIO2 0.21), where she was intubated and mechanical ventilation was applied, with administration of vasoactive amines and admission to the ICU. Two months previously she had reported general malaise, 10kg weight loss, and in the last week, fever of up to 39°C, cough and mucopurulent expectoration.

Examination showed that she was severely underweight (BMI 14.2), with global loss of breath sounds in both pulmonary fields. Analytical parameters on admission were 16200 leukocytes/mm3 (81% neutrophils, 9% lymphocytes, and 10% monocytes), ESR 11mm/1h, blood glucose 174mg/dl, AP 133IU/l, gamma GT 231IU/l, LDH 392IU/l, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein 9mg/dl. Other parameters – complete blood count, hemostasis and biochemistry – were normal, including procalcitonin and immunoglobulins. Urine sample was negative for Streptococcus pneumoniae antigen and positive for Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 antigen, so the initial empirical treatment with ceftriaxone and azithromycin was switched to levofloxacin.

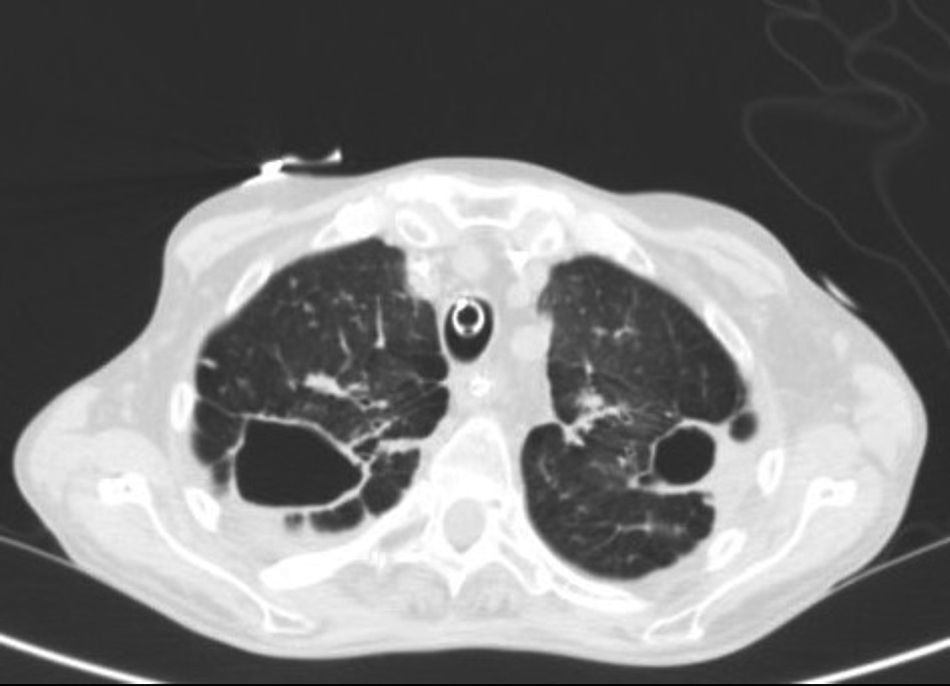

Chest radiograph revealed fibrocavitary tracts in both upper fields with signs of air trapping, confirmed on CT (Fig. 1). No particular findings were revealed in the head or the abdomen. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed, showing signs of inflammation of the bronchial mucosa, and bronchial aspirates were obtained for standard and mycobacterial culture. Standard culture techniques showed growth of saprophytic flora, with no Legionella spp. or fungal strains. No alcohol-acid resistant bacilli (AARB) were observed on Ziehl-Neelsen staining. A serology study for HIV and IgM antibodies against Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Coxiella burnetii, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Legionella pneumoniae and anti-Chlamydophila psittaci indirect immunofluorescence were negative. Blood cultures and Mantoux were also negative.

One week after admission to the ICU, bronchoscopy was repeated, with similar findings and negative PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (GeneXpert®, Cepheid). After extubation, a Stage IVA epidermoid carcinoma at the base of the tongue was diagnosed. Three weeks later, AARB growth was observed in 2 bronchial aspirates obtained on bronchoscopy. Solid phase hybridization was performed using GenoType® Mycobacterium CM/AS (Hain Lifescience, Germany), but the strain could not be identified, so it was sent to the Mycobacteria Genetic Group of the Universidad de Zaragoza, where it was identified as Mycobacterium szulgai (M. szulgai). Treatment began with rifampicin 600mg, ethambutol 600mg, and azithromycin 250mg/day, and continued for 10 months until she died due to tumor progression. Initially, despite treatment for her cancer with chemotherapy and radiation therapy, the patient's clinical and radiation therapy progress was good, and no M. szulgai growth was encountered in follow-up sputums.

According to the ATS/IDSA criteria, isolation of M. szulgai is associated with real lung disease to a greater extent than other NTM.5,6 Although it has been described in immunosuppressive states and with the administration of drugs, cancer, and HIV infection, this association is considerably rarer than with other NTM.7–13 It is highly unusual for a diagnosis of M. szulgai to be the first manifestation of an underlying tumor, but the patient presented other risk factors for developing the disease, such as chronic alcoholism, smoking, and COPD.

It is more common in men (>85% of patients reported), and can appear at any age, although most individuals are, on average, around 50–60 years old. In over 2 thirds of patients, disease is limited to the respiratory system, and the radiological and clinical picture is indistinguishable from that of M. tuberculosis and other NTM. Extrapulmonary disease and disseminated disease have also been described in immunocompromised patients.

In line with the ATS/IDSA guidelines, Philley and Griffith recommend a combination of at least 3 oral drugs: ethambutol 15mg/kg/day, rifampicin 600mg/day or rifabutin 150–300mg/day, and azithromycin 250mg/day or clarithromycin 500mg/12h, or moxifloxacin 400mg/day, for at least 12 months after a negative culture: most patients respond well.14

The patient met ATS/IDSA criteria for pulmonary disease due to M. szulgai, since she had consistent radiological lesions on Rx and CT, M. szulgai was isolated in 2 samples of bronchial aspirate obtained 1 week apart, and the presence of other mycobacteria, other pathogens, and lung cancer were ruled out. Clinical and radiological progress of the infection with rifampicin, ethambutol, and azithromycin treatment was good, even though the patient later died due to progression of the tumor at the base of the tongue.

We would like to thank Dr. Sofia Samper of the Mycobacteria Genetic Group of the Universidad de Zaragoza for her kind assistance in identifying M. szulgai.

Please cite this article as: Milagro Beamonte A, Briz Muñoz E, Torres Sopena L, Borderías Clau L. Enfermedad pulmonar producida por Mycobacterium szulgai. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:353–354.