Lung cancer (LC) is the fifth leading cause of death worldwide.1 Unfortunately, at the time of diagnosis almost half of patients have distant metastases (most frequently in the brain, bone, liver, and adrenal glands),2 and it is estimated that 60% of patients with early stage disease may present micrometastases.3

The metastatic spread of CP in the skeletal muscle is an uncommon finding (<1%), associated with poor prognosis and an average life expectancy of 6 months. Three theories have emerged to explain the low affinity of tumor cells for muscle tissue: the immunological theory (the role of humoral and cellular immunity); the metabolic theory (possible involvement of oxygen fluctuations, variable pH, and lactic acid production); and the mechanical theory (possible protective effect of muscle contractions due to high pressure and variable blood flow).3

The clinical presentation of musculoskeletal metastases (MSM) varies widely, from lesions that can be asymptomatic or painful and/or palpable, or can cause functional limitation in the affected area, to incidental findings in complementary imaging test.2–4 The initial diagnostic approach in patients with suspected MSM usually begins with a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest. Surov et al. proposed 5 radiologic patterns4 for the characterization of MSM: type I: intramuscular mass; type II: abscess-like lesion; type III: diffuse muscle tissue infiltration; type IV: lesion with multiple calcifications, and type V: intramuscular bleeding pattern.3 The use of additional techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (very useful for differentiating between MSM and primary malignant muscle lesions), and positron emission tomography with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (greater proven sensitivity for detecting MSM and skin lesions) should also be considered.3 However, a definitive diagnosis requires histological analysis of the lesion.

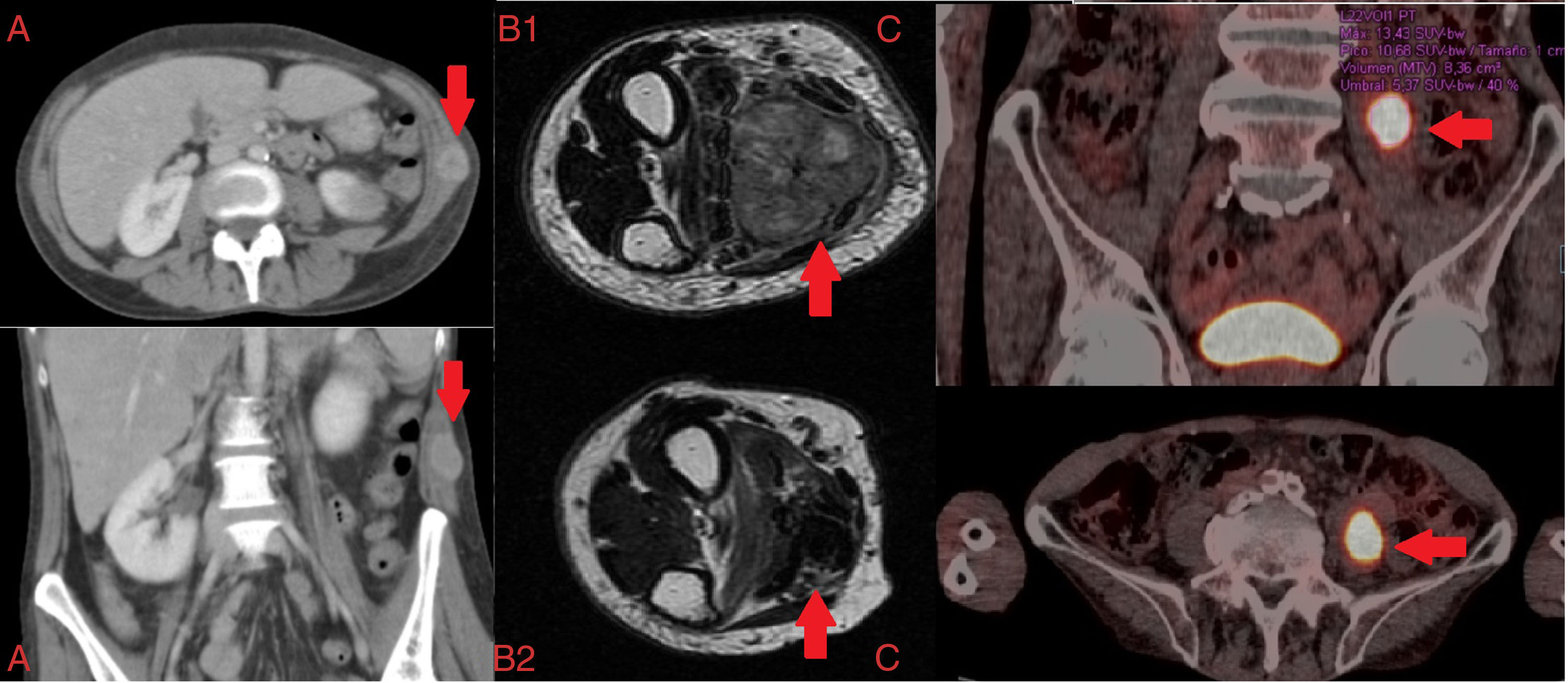

Below, we discuss 3 clinical cases of MSM in patients with LC and the different imaging diagnostic tests that were performed. The first patient was a 57-year-old woman who reported constitutional symptoms, dyspnea, and a non-painful deep adherent mass in the right flank. Chest CT revealed a right hilar lesion with multilevel mediastinal involvement, and a tumor on the left abdominal oblique muscle, classified according to its CT radiological pattern4 as type I (Fig. 1A). The second case was an 83-year-old man with a painful tumor (necrotic cystic mass measuring 35×26×46mm on the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle of the hand) and a 4-month history of lack of function in the right forearm. The extension study revealed 2 pulmonary masses, consistent with pulmonary adenocarcinoma (tumor classification cT4NxM1b1). The patient received local palliative radiation therapy and chemotherapy with platinum/pemetrexed (Fig. 1B1 and B2). The third case was a 73-year-old man receiving active treatment guided by sensitivity testing results for documented Mycobacterium xenopi infection. Positron emission tomography showed a lesion measuring 40×25mm with central cavitation in the left upper lobe (SUVmax 28.38) (Fig. 1C) and a hypermetabolic focus located in the left iliopsoas muscle with SUVmax 13.43, suggestive of MSM.

(A) Axial and coronal computed tomography: musculoskeletal metastasis on the left abdominal oblique muscle. (B) Axial T2 magnetic resonance image: musculoskeletal metastasis on flexor digitorum superficialis muscle of the hand; (B1) pre-treatment; (B2) post-treatment. (C) Chest PET-CT: musculoskeletal metastasis on the left iliopsoas muscle.

In all 3 cases, histological specimens were obtained for characterization, and the results were consistent with high grade undifferentiated tumor, striated muscle infiltrated with adenocarcinoma, and squamous carcinoma, respectively, all originating in the lung. The clinical progress of the patients differed: death 2 weeks after diagnosis, pain control, and reduced tumor size (Fig. 1B2) after targeted oncological treatment; clinical stabilization was achieved in the last 2 cases described.

Given the low prevalence of MSM, a detailed differential diagnosis that includes the more common malignant and benign entities (sarcomas, primary muscle lymphomas, and myxomas/hemangiomas) must be made. Although no clinical guidelines are available for the specific management of MSM, treatment is based on general oncological principles guided by clinical picture, site, and life expectancy, and approaches include observation, surgical excision (persistent solitary lesions after a period of remission), chemotherapy and radiation therapy (useful for pain control and for the reduction of tumor size).2–4

The correct identification of MSM in LC patients is essential for clinical management and prognosis. For this reason, the possible neoplastic etiology of any muscle lesion, whether symptomatic or not, detected in LC patients must be evaluated with combined radiological procedures and histological confirmation of the lesion.

Please cite this article as: de Vega Sánchez B, Lobato Astiárraga I, Lopez Castro R, López Pedreira MR, Vicente CD. Metástasis musculoesqueléticas: hallazgo infrecuente asociado al cáncer de pulmón. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:390–391.