Strongyloides is a nematode that can repeat autoinfection cycles within the human host, perpetuating a chronic infection which may go unnoticed.1 Migration of the larvae through the lungs can cause manifestations such as cough, dyspnea or wheezing,1–3 but the most typical manifestation is as a subclinical form of Löffler's syndrome. However, in immunocompromised patients, the cycles are accelerated, the parasite may even disseminate to other organs, and mortality can be as high as 87%.4 We report a case of Strongyloides stercoralis infestation with severe lung involvement.

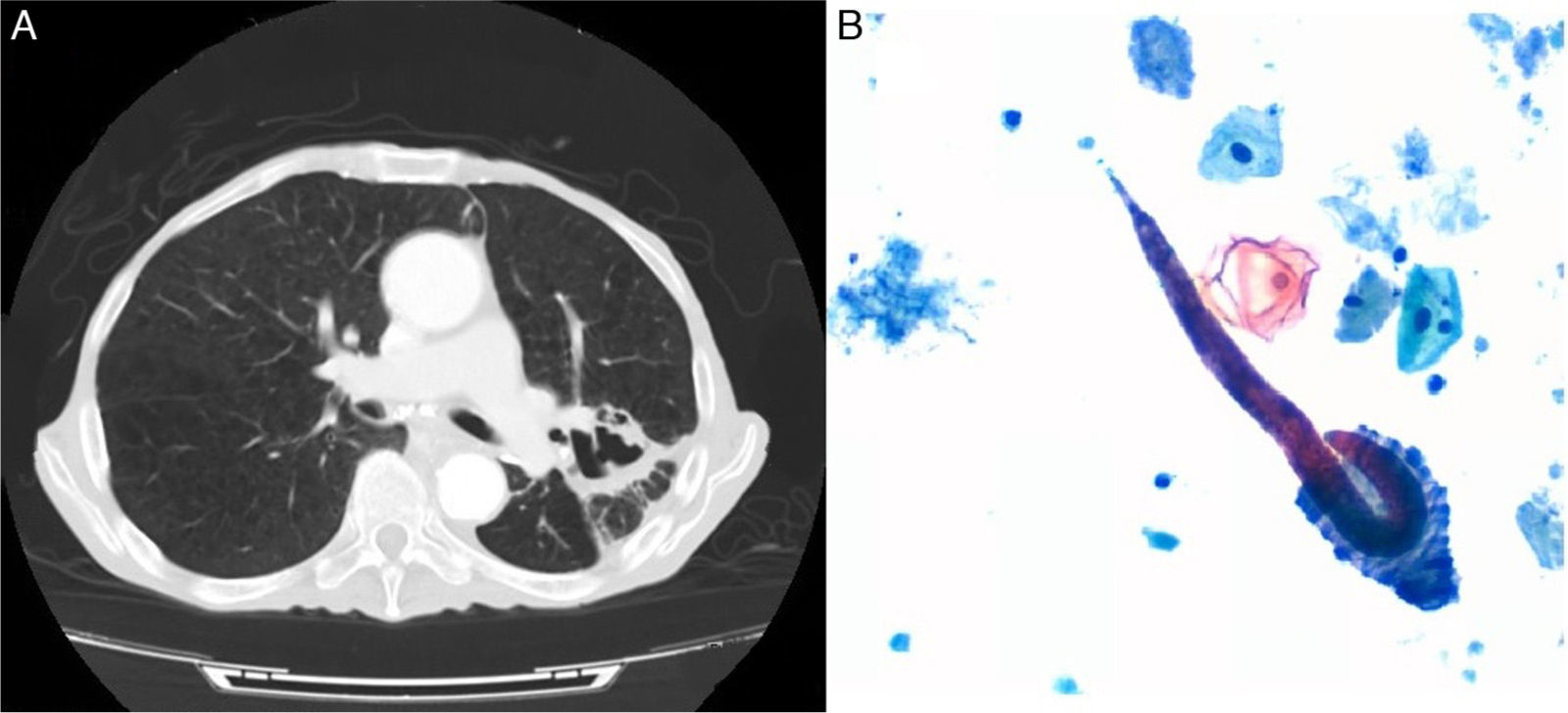

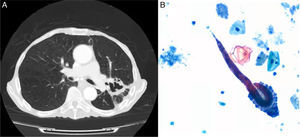

An 84-year-old man, active smoker with an accumulated consumption of 60 pack-years, hypertensive, gastrectomized 7 years previously due to gastric cancer, and operated again for splenic abscess requiring splenectomy. He had worked as a farmer, and had occasionally watered the land in his bare feet. He consulted due to a 5-month history of asthenia, dysphagia, low-grade fever, anorexia, and weight loss. He had been admitted to another hospital for 14 days with a diagnosis of pneumonia, and received ertapenem, clindamycin, corticosteroids and bronchodilators. Seven days after discharge, he was brought to our hospital due to progressive deterioration. Physical examination revealed cachexia, crackles in the left hemithorax, and slightly tender abdomen. Clinical laboratory testing showed increased acute phase reactants, without eosinophilia. Computed axial tomography showed consolidation in the left upper lobe, areas of cavitation with irregular walls (Fig. 1A), and marked dilation of the loops of the small intestine. The patient was treated with piperacillin–tazobactam and amikacin, without improvement. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed, showing a greenish liquid secretion, shown on bronchial aspirate cytology to contain Strongyloides stercolaris filariform larvae (Fig. 1B). In view of the diagnosis of pulmonary infestation, albendazole and ivermectin were added to the therapeutic regimen, but the patient progressively worsened and died 26 days later.

Strongyloides stercolaris filariform larvae penetrate through the skin and travel through the venous system to the right heart cavities, and from there to the lungs. They pass through the glottis to the digestive system where they lay their eggs, releasing non-infectious rhabditiform larvae. These can transform to invasive filariforms during the autoinfection cycles, penetrating the intestinal mucosa to complete the cycle,5 producing ulcerations making the patient susceptible to bacteremia. In pulmonary infestation, larvae infiltrate the alveolar and vascular spaces, progressing to diffuse hemorrhagic interstitial pneumonitis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or lobar pneumonia, as in the case discussed here.2,3

Our patient worked barefoot in the fields, which may explain the port of entry, while various factors may have precipitated the infestation: gastrectomy with the consequent achlorhydria, absence of spleen, malnutrition, and corticosteroid treatment.1–4 It is interesting to note that Strongyloides stercolaris parasitosis is not a strictly exotic disease: it is also endemic on the Mediterranean coast,2 with the highest prevalence occurring in farmers in certain regions. It seems a reasonable approach to detect larvae in risk situations, particularly before initiating immunosuppressive treatments, to prevent disseminated disease and death.1,3,4

We thank the Pathology Department of the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia for their help and collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Esteban Ronda V, Franco Serrano J, Briones Urtiaga ML. Infestación pulmonar por Strongyloides stercoralis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:442–443.