Pulmonary benign metastasizing leiomyoma (PBML) is a rare disease which occurs in women of child-bearing potential with a history of uterine leiomyoma (UL). Although these tumors are histologically benign, they can metastasize to other organs, such as the lung.1

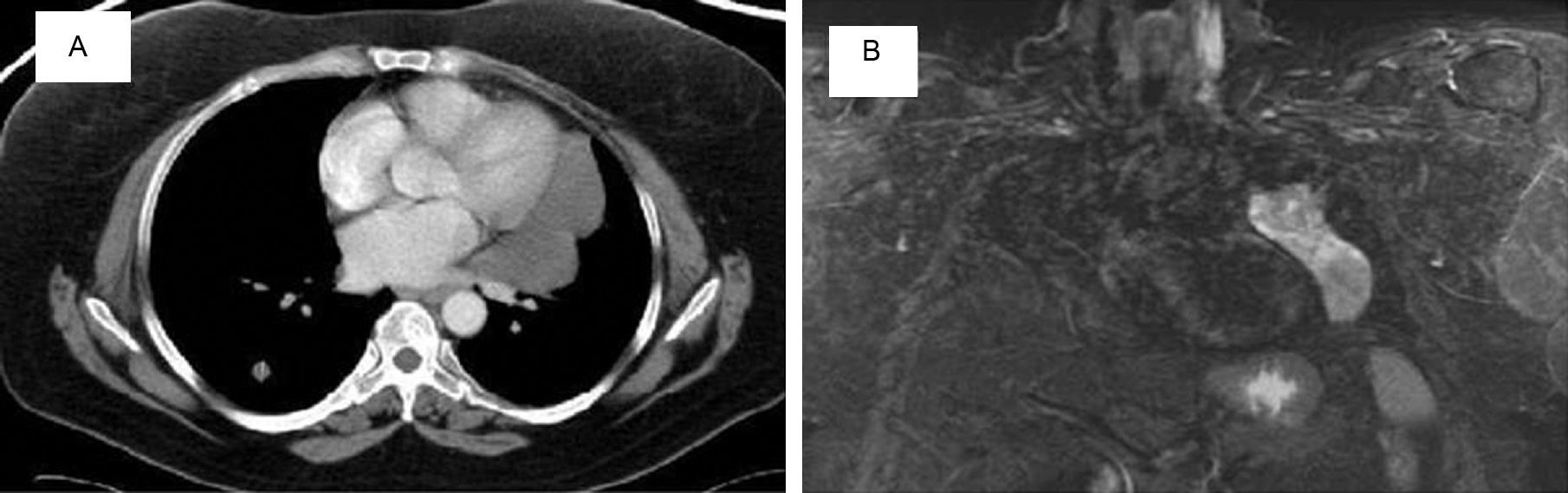

We report the case of a 53-year-old woman with chronic abdominal pain, who was referred after a computed axial tomography (CAT) (Fig. 1) revealed a 6cm mass in the left ovary, multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules, and an 11cm solid-cystic mass in the left paramediastinum. She had a history of hysterectomy for UL 12 years previously; she was a non-smoker and asymptomatic. Lung function, bronchoscopy, and laboratory test results were normal. No uptake was found on PET-CAT, while magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 1B) identified a lobulated, well-defined, heterogeneous paramediastinal mass.

Biopsy of a nodule revealed smooth muscle tissue with no atypical cells, low mitotic index, actin/desmin expression, and positive estrogen/progesterone receptors, consistent with leiomyoma. Resection of the pelvic and paramediastinal masses confirmed that both were leiomyomas. The patient received tamoxifen 20mg/day and triptorelin 3.5mg/month, and is currently stable.

UL is the most common gynecological tumor in fertile women. On rare occasions, it grows outside the uterus, when it is called PBML. Around 100 cases have been published since the first report by Steiner in 1939.1

PBML is characterized by multiple extrauterine nodules of smooth muscle tissue, a history of hysterectomy for UL, and a latency period of 3–20 years.2,3 The most commonly affected organ is the lung, but it may also embed in the pleura, peritoneum, vena cava, or the heart.

Most occurrences are asymptomatic, and it presents as an incidental finding of well-defined multiple pulmonary nodules of varying sizes,2 70% bilateral, and 17% unilateral. It presents only exceptionally as a solitary nodule.3 More uncommon are the miliary pattern, or cystic or cavitated lesions.

Histological features include actin and desmin expression, positive estrogen and progesterone receptors, and benignity, a low mitotic index, no atypical cells, and no tumor necrosis.3 It is produced by independent multifocal proliferations of smooth muscle which respond to hormonal stimulus, or by hematogenous dissemination of an initial UL.3,4 Cytogenetic studies suggest a monoclonal origin. Its course is generally indolent, except when the site, size or number of lesions cause complications.5

The therapeutic approach to PBML is conservative or surgical, and primary excision is the intervention of choice, whenever possible.4 In our case, the paramediastinal mass was resected after it increased in size, to avoid local complications due to compression of the adjacent mediastinal structures, and to confirm the nature of this large cystic lesion that differed greatly from the other nodules. Resection of these lesions is recommended, in order to avoid complications, such as massive hemoptysis, and to rule out low-grade leiomyosarcoma. Hormone treatment is recommended for inoperable lesions.4

To conclude, PBML should be taken into consideration in women of child-bearing age with multiple pulmonary nodules and history of UL.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Ferrer P, Chiner E, Sancho-Chust JN, Arlandis M. Leiomiomatosis pulmonar benigna metastatizante, una causa excepcional de nódulos pulmonares. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:226–227.