The World Health Organization defines giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone as a benign but locally aggressive primary bone neoplasm composed of a proliferation of mononuclear cells that include numerous disperse macrophages and osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells.1 Extraosseous forms of GCT occur that have an identical histology to GCTs of bone. It is exceptional to encounter these tumors in the lung. We report the case of an aggressive primary GCT of the lung.

This was an 80-year-old male patient, former smoker of 50 pack-years, being examined for hemoptysis. Computed tomography (CT) showed a solid, hypodense, right pulmonary mass measuring 8×5×5cm, with polylobulated borders, and homogeneous uptake of contrast material, located in the confluence of the oblique and horizontal fissures, below the hilum, centered in the middle lobe, but with lobulationes invading the apical segment of the right lower lobe (RLL) and the anterior segment of the right upper lobe (RUL), suggestive of primary bronchopulmonary neoplasm. No evidence of metastatic disease was seen on preoperative PET–CT. Right pneumonectomy was performed with aortopulmonary and subcarinal lymphadenectomy; postoperative progress was favorable.

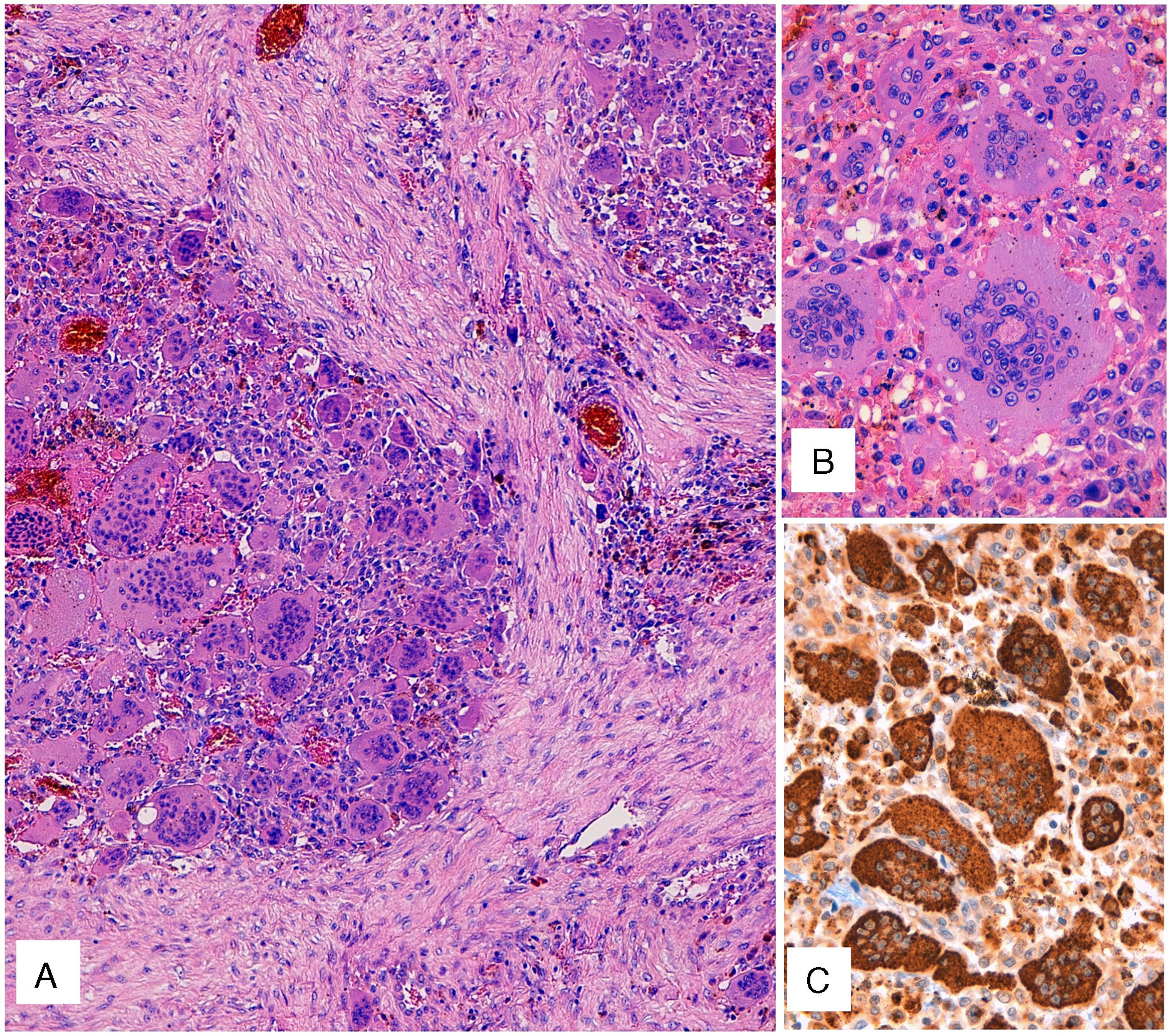

Gross examination of the surgical piece showed a multinodular mass of hemorrhagic appearance, measuring 7.6cm, located mainly in the middle lobe, with a satellite nodule measuring 1.4cm in the same lobe. Histologically, the tumor consisted of proliferation in a solid pattern with medium-sized mononuclear cells and eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei were round or oval, with finely granular chromatin, and contained small nucleoli with no cytological atypia or mitotic figures. Numerous osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells were also observed (Fig. 1A), many of which had numerous nuclei (Fig. 1B) with no atypia or significant mitotic activity. After extensive sampling of the piece, no carcinoma, sarcoma or other tumor components were identified.

(A) Hematoxylin–eosin staining. Solid pattern cell proliferation with mononuclear cells and numerous osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells. (B) Detail of the osteoclast-like giant cells with numerous nuclei, without atypia or significant mitotic activity. (C) CD68 immunostaining of both the mononuclear component and the osteoclast-like giant cells.

The immunohistochemical study, including both the mononuclear component and the osteoclast-like giant cells, was positive only for CD68 (Fig. 1C). Immunoreactivity was negative for a wide range of epithelial markers (CK7, CK20, panCK [AE1/AE3], epithelial membrane antigen, CK34BE12), actin, desmin, CD34, TTF1, napsin, and S100. These data pointed to a diagnosis of GCT.

Two and a half months after surgery, the patient consulted for pain in the area of the surgical wound and in the right inguinal region. Bronchoscopy revealed an intrabronchial tumor in the stump of the pneumonectomy. On CT, 3 metastatic lesions were identified: one in the subcutaneous cell tissue of the root of the left thigh, another within the left vastus lateralis muscle, and third bone lesion in the left iliac crest with cortical destruction, associated with a soft tissue mass. A biopsy of the bronchial stump and one of the metastatic lesions showed similar histologic features to the primary tumor. Immunostaining for p63 was performed on these specimens, with focally positive results. Palliative cancer treatment was administered, and the patient died 8 months after diagnosis.

GCT represents 4%–5% of primary bone tumors and the peak incidence occurs in skeletally mature young adults between the ages of 20 and 45 years, with a slight predominance of women. Local recurrence is common, but lung metastases occur in 2% of cases. There is no grading system that provides a meaningful prognosis.1

Pure extraosseous GCTs with a histology identical to that of bone tumors are very rare, and have been described, in order of frequency, in the pancreas, breast, lung, stomach, thyroid gland, and urinary tract; they are particularly rare in the lung.2 The nomenclature of this entity is confusing, as the mere presence of giant cells does not imply a diagnosis of GCT, since other types of tumor can also have osteoclast-like giant cells.

The differential diagnosis includes metastasis of a primary GCT of bone and malignant mesenchymal or epithelial tumors that contain osteoclast-like giant cells.

We ruled out the first possibility by the absence of a history of bone lesions and skeletal tumors in the preoperative study, and by the age of the patient.3 If there is an additional identifiable tumor component (carcinoma or sarcoma), the tumor should be classified for all intents and purposes as carcinoma or sarcoma with osteoclast-like giant cells. In our case, this component was not identified and the epithelial markers were negative, so this diagnosis could be ruled out. In this regard, some studies describe the use of p63 immunostaining to identify GCTs of bone, a technique that we also used.4 This staining is useful for supporting the diagnosis of GCT over other tumors. It is important to be aware of this technique, to avoid mistaking the diagnosis for squamous cell carcinoma, particularly when epithelial markers are negative.

Some studies suggest a more aggressive clinical behavior in the visceral forms of GCT than in the osseous counterpart, as was observed in our case.3,5 Very few reports are available of cases of primary GCTs of the lung that meet the strict criteria for this diagnosis: absence of histological evidence of other tumors (carcinoma or sarcoma). In our review of the literature, we only found 6 cases of primary GCTs of the lung. Among these cases were 3 men, aged 63, 61, and 40 years, and a woman aged 77 years. Follow-up data are available for only 1 of the patients who was disease-free at 15 months. No clinical or epidemiological data were provided for the other 3 cases.5–11

In conclusion, we report a very rare type of primary lung tumor, the pathogenesis of which remains to be clarified, with an aggressive course, that poses problems for histopathological differential diagnosis. It is important that new cases are published to establish guidelines with regard to the prognosis and treatment of these tumors.

Please cite this article as: Pabón-Carrasco S, Vallejo-Benitez AM, Pabón-Carrasco M, Rodriguez-Zarco E. Tumor de células gigantes primario de pulmón. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019;55:60–62.