Primary lung tumors are extremely rare in childhood, although the exact incidence is unknown.1–4 They are classified into 2 broad groups according to the degree of malignancy2,5; benign tumors include inflammatory pseudotumor and hamartoma, whereas malignant tumors (accounting for approximately 70%–75% of cases) include primary tumors and metastases, usually from extracranial tumors.5 Primary tumors include bronchial carcinoid tumors (the most common primary lung cancer), followed by mucoepidermoid tumors, bronchogenic tumors, pleuropulmonary blastoma, and lymphoma.1,2,5

Diagnosis is based on imaging and pathology studies,2 but often delayed by the low incidence of this type of disease.2,5

We performed a retrospective analysis of the cases of endobronchial tumors diagnosed in our hospital between 2000 and 2017. We found 4 patients, 3 girls and 1 boy, aged from 3 months to 12 years, with a diagnosis of endobronchial tumor. We describe each case briefly below.

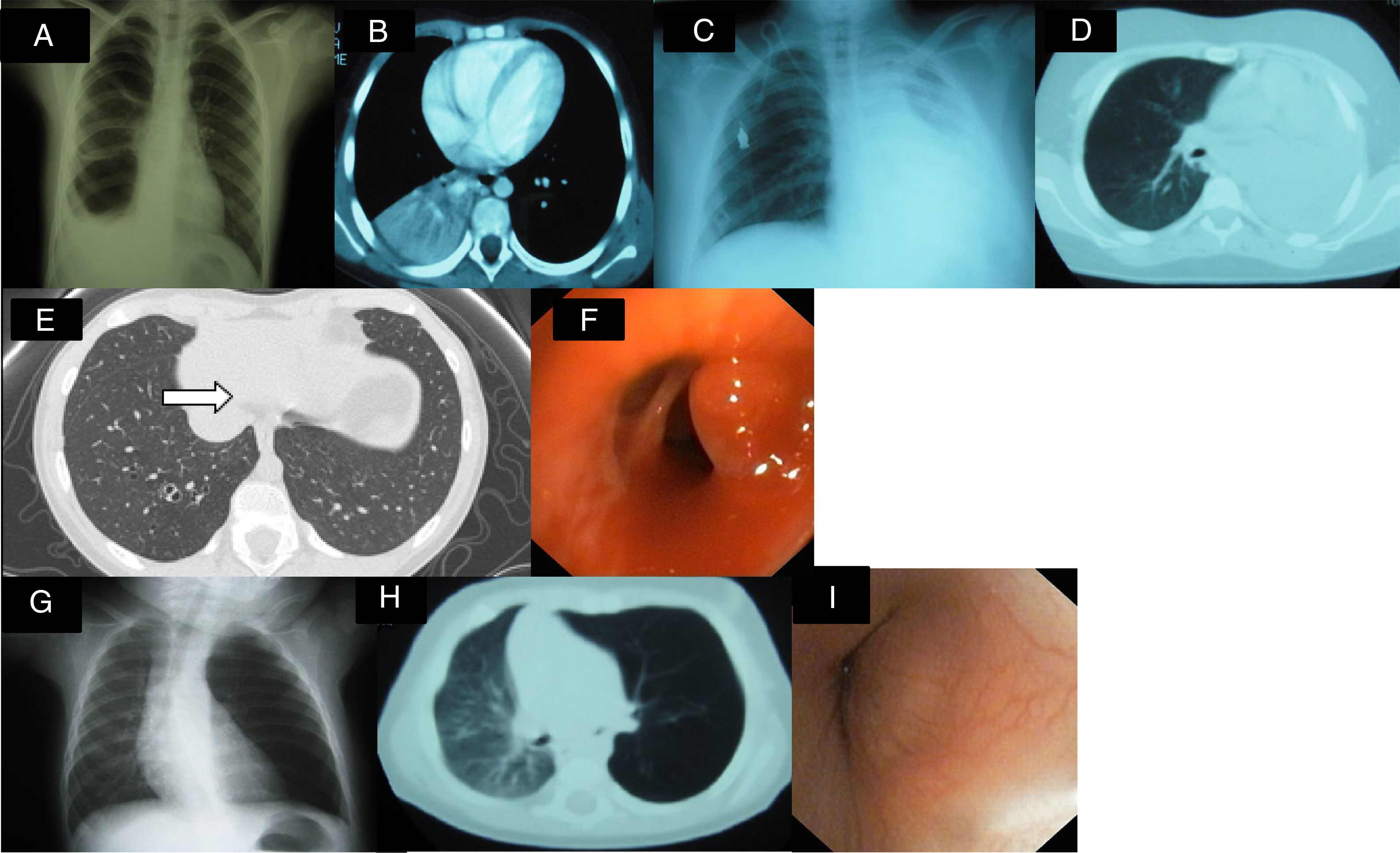

Clinical case 1: a 9-year-old girl under investigation for an image of persistent consolidation/atelectasis in the right lower lobe (RLL). Clinical picture: 2-month history of intermittent febrile syndrome, cough, and weight loss. The initial diagnosis was pneumonia, and antibiotic treatment was administered, with no response. Personal history: episodic asthma with sensitization to dust mites and pollens and 3 previous episodes of pneumonia. Physical examination: hypoventilation in lower third of the right hemithorax. Additional tests: Complete blood count, biochemistry, hepatic and renal profile normal; ESR 113mm/h; Mantoux 0×0mm; Sweat test negative; α-1 antitrypsin normal. AP chest X-ray (Fig. 1A) consolidation in right lung base. Lung CT (Fig. 1B): consolidation in RLL, atelectasis in RLL associated with small right posterior pleural effusion, and right paratracheal, subcarinal, and hilar lymphadenopathies; urinary catecholamines normal. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy: tumor mass at entrance to bronchus of the right basal segments, almost entirely obstructing the bronchial lumen. Pathology report: bronchial carcinoid tumor. Right middle and lower lobectomy was performed with subsequent favorable progress.

(A) Consolidation in right lung base and small ipsilateral pleural effusion. (B) Consolidation and atelectasis in RLL, associated with small right posterior pleural effusion. (C and D) Massive atelectasis of left lung. (E) Lesion in the interior of the basal segmental bronchus with a hyperdense punctiform image of polypoid appearance. (F) Fiberoptic bronchoscopy showing a reddish, pedunculated, well-defined mass. (G) Air trapping in left lung with slight tracheal shift. (H) Lung CT: stenosis of left main bronchus and left pulmonary hyperinflation. (I) Non-pulsatile mass in entrance of left main bronchus, obstructing 70%–80% of lumen with vascularization of mucous membrane.

Clinical case 2: a 12-year-old boy under investigation for massive atelectasis of the left lung. Clinical picture: 2–3 month history of dry cough, vomiting, and intermittent fever. He received 2 cycles of antibiotic treatment with transient improvement. Examination: hypoventilation in left hemithorax. Additional tests: complete blood count, biochemistry, hepatic and renal profile normal; ESR 94mm/h; LDH 1207IU/l; enolase, catecholamines, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy normal. AP chest X-ray (Fig. 1C) and chest CT (Fig. 1D): massive atelectasis of left lung. Abdominal CT: right intrarenal mass. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy: left endobronchial mass. Pathology: CD45 and CD20-positive lymphocytic cells, consistent with B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). FNA of right renal tumor: B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Given these results, the patient was diagnosed with Stage III NHL, primary location unclear. He was treated with chemotherapy and remains disease-free after 5 years.

Clinical case 3: 10-year-old girl, asymptomatic, with no significant history, referred due to contact with tuberculosis. Additional tests: Mantoux 0×0mm. Pulmonary CT: occupation of airspace in basal and lateral segments of the RLL with a tree-in-bud image, suggestive of infectious bronchiolitis. In view of this situation, anti-tuberculosis treatment was administered for 6 months. Second Mantoux test negative. Follow-up lung CT (Fig. 1E): hyperdense punctiform image of polypoid appearance, partially occupying the lumen of the bronchus of the left basal segment. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy (Fig. 1F): 2 reddish, pedunculated, well-defined masses in the RLL bronchus, that were resected. Pathology report: inflammatory polyp with no granulomas; culture and PCR of bronchoalveolar lavage and sputum negative. Favorable progress.

Clinical case 4: 3-month-old infant who had been rejecting feeds for 10 days. No history of interest. Physical examination: hypoventilation in left hemithorax. Additional tests: chest X-ray (Fig. 1G) showing air trapping in left lung with no significant shift of mediastinum or contralateral lung. Lung CT (Fig. 1H): stenosis of left main bronchus and left pulmonary hyperinflation. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy (Fig. 1I): non-pulsatile mass in the exit of the left main bronchus, obstructing 70%–80% of lumen. Pathology of resected specimen: myofibroblastic tumor. The tumor was resected by thoracotomy, and progress was favorable.

In our series, we treated 1 myofibroblastic tumor or inflammatory pseudotumor, 1 bronchial carcinoid tumor, 1 endobronchial polyp, and 1 endobronchial metastasis of a B cell NHL. According to the literature consulted, most patients have symptoms on diagnosis,2–4 the most common being persistent cough, repeated respiratory infections, and bronchospasm. Two of our patients had dry cough and intermittent fever, 1 had hemoptysis, and 1 rejected feeds.

Myofibroblastic tumor (case 4) behaves like a benign tumor and is considered an inflammatory response to previous stimulus.5,6 It is one of the most common benign endobronchial tumors. Growth is slow and progressive, it tends to be locally invasive, and recurs if not treated.5,6 Treatment of choice is resection.4

Bronchial carcinoid tumor is a tumor of neuroendocrine origin.5,7 It often presents initially as hemoptysis or repeated infections,5,7,8 while carcinoid syndrome is rare. Bronchial carcinoid tumors are typically central and well-differentiated, and prognosis after resection is favorable.1,2,5,8

Endobronchial polyps (case 3) might develop as an uncommon manifestation of endobronchial tuberculosis,3,8,9 that could not be demonstrated in our case.

Pulmonary lymphoma is defined as lung/endobronchial involvement with no previous diagnosis of extrapulmonary disease.2,10 Primary endobronchial B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is extremely rare, and dissemination of an undiagnosed primary tumor cannot be ruled out,10 as occurred in case 2 when the abdominal CT was performed.

In conclusion, a diagnosis of primary endobronchial tumors, while uncommon in children, must be considered in the case of persistent bronchial obstruction, infection or recurrent pulmonary collapse. Histological variety and grades of malignancy vary widely. Treatment is generally surgical, and can be either combined with chemotherapy or not. In case of metastasis, the primary tumor must be treated. Progress after the appropriate treatment is good in general, as we have shown in our series. However, long-term follow-up is recommended, due to the risk of recurrence.11

Please cite this article as: González Fernández-Palacios M, Gutiérrez Carrasco JI, Delgado Pecellín I. Tumores endobronquiales primarios en edad pediátrica. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:587–589.