Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE) is a rare condition firstly described in 1992 by Amitani et al. under the name of upper lobe pulmonary fibrosis1 and then in 2004 by Frankel et al. as pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis.2 Later in the updated 2013 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification, idiopathic PPFE (IPPFE) was included as a new clinic-pathological entity.3 In this condition, both radiology and histology show typically pleural thickening and subpleural fibrosis in the upper lobes, with the involvement of lower lobes being less marked or absent.3•5 Besides the rarity of the idiopathic form, PPFE is often associated with a multiplicity of clinical entities namely other interstitial lung diseases (ILD) as Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) or Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis, bronchiectasis, connective tissue disorders, recurrent infections, bone marrow/organ transplant, or ambient exposure as silica or asbestos.4,6,7 Interestingly, PPFE can also occur in a familiar context, and even a particular association with telomere length mutations have been described.8 As other particular pulmonary radiologic/histologic pattern, PPFE can also be associated with toxicity induced by drugs.4,9 At present, cases with chemotherapy either associated or not with radiation and methotrexate have been reported.9

Here we present a case of PPFE diagnosed in a patient under amiodarone prescription, an association not previously described.

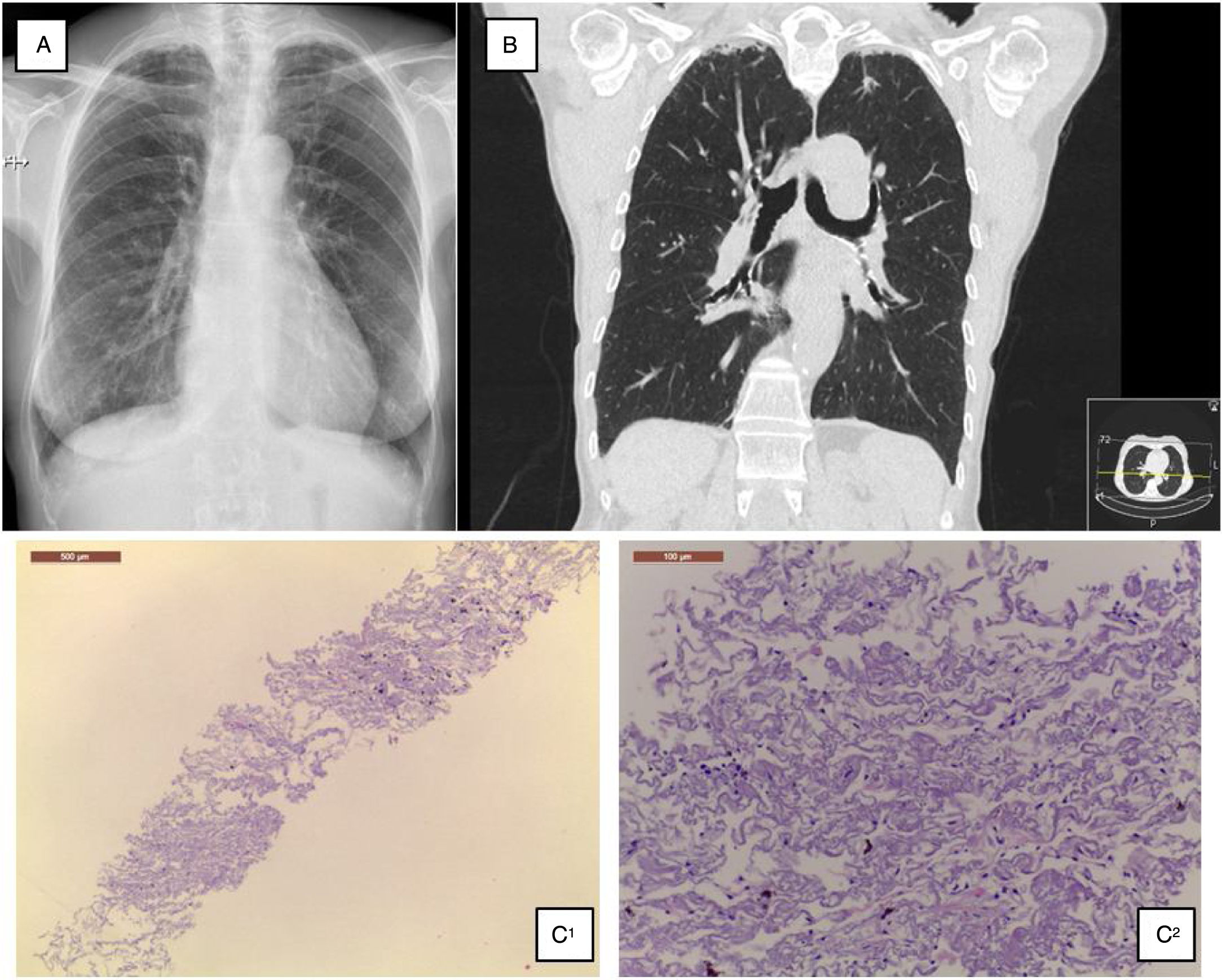

A 68-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to ILD outpatient clinic with recurrent episodes of a dry cough for the past two years, significantly worsened in the last six months, and consolidations in both upper lobes in thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan. She had atrial fibrillation diagnosed five years before, under amiodarone and warfarin since that time. Additionally, nimodipine was also prescribed due to arterial hypertension since its diagnosis. Physical examination did not show any relevant remarks, namely in the thoracic evaluation. Besides the values in the normal range concerning hemogram, hepatic and renal function, the serum autoimmune panel was negative. Any microorganism was found in the sputum. Lung function tests showed normal lung volumes (forced vital capacity • 144.5%, forced expiratory volume in the 1° second • 129.4%, total lung capacity • 119%) and diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide of 79.3%. Additionally, arterial blood gases had values into the normal range, and in six-minute walk test, the patient walked 452m, without significant oxygen desaturation (minimum oxygen saturation 95%). Chest radiograph showed subpleural thickening at upper lobes (Fig. 1A), predominantly in the right hemithorax; these findings were more evident in the chest HRCT scan, associated with parenchymal reticulation and peripheral traction bronchiectasis at upper lobes, with no abnormalities at lower lobes (Fig. 1B). Chest radiographs performed previously and during the amiodarone prescription did not show any relevant features. The histology obtained by computed tomography-guided transthoracic biopsy in the left lung apex showed fibrosis, with dense collagen and elastic fibres, compatible with PPFE. (Fig. 1C) After discussion in a multidisciplinary meeting, since clinical, imaging and histology all were compatible with PPFE, this diagnosis was established. After a careful evaluation did not found any of the potential causes previously described added to the fact that one of the most frequent amiodarone side effects is lung toxicity, with a multiplicity of patterns, amiodarone was then considered as a potential cause.

(A) Chest radiograph shows bilateral apical subpleural thickening; (B) coronal CT imaging shows subpleural thickening and reticular opacities with traction bronchiectasis in the parenchyma at the upper lobes, more predominant in the right side; (C) 1 • low magnification showing fibroelastotic scarring; 2 • at high magnification the typical mixture of fragmented elastic fibres and collagen.

After a cardiac revaluation and based on this hypothesis, amiodarone was suspended, upholding both nimodipine and warfarin. After that, a significant decrease in the frequency and intensity of cough episodes was reported by the patient, and during 12 months of follow-up, a clinical, functional and imaging stability was noticed.

The present clinical case describes PPFE as another possible lung toxicity pattern induced by amiodarone.

As previously stated, PPFE is considered a rare idiopathic interstitial pneumonia and more often is associated with a variety of other respiratory disorders including other ILD as IPF.4•6 There are also some reports suggesting PPFE as another potential radiologic/histology pattern associated with drug-induced lung diseases, namely its association with chemotherapy schemes containing alkylating agents as cyclophosphamide or carmustine (BCNU).9

According to the clinical cases reported in the literature, PPFE arises in adults with a median age of 57 years without sex predilection.3,4 In this report, the disease presentation occurred in more advanced age, 68 years, but with the usual radiologic features of bilateral and peripheral upper lobe thickening, with no involvement in lower lobes.

Regarding clinical presentation and course, approximately half of the patients have recurrent infections, others exertional dyspnoea occasionally associated with a dry cough and sometimes PPFE is diagnosed in an asymptomatic patient as a radiologic finding.3,4 The outcome seems to be also variable and mostly unpredictable, encompassing cases with prolonged stability to cases with disease progression to respiratory failure and death.3•5 Pneumothorax is a frequent complication.10 The patient described in this clinical report had a recurrent and intense dry cough without any other respiratory symptoms or constitutional signs.

Besides the treatment of the underlying conditions, PPFE management, namely in idiopathic forms, is still unclear, but the prevention and early treatment of infections are recommended since it can have a direct influence in the disease progression.4 Although some reports considering a potential benefit, the role of immunosuppression is still unknown.4 In the actual clinical case, besides the amiodarone cessation, any other therapeutic was considered due to the favourable clinical evolution with the symptom resolution and the absence of lung function impairment.

Amiodarone is associated with several forms of pulmonary toxicity including interstitial pneumonitis, eosinophilic pneumonia, organising pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH), pulmonary nodules and masses, and rarely pleural effusions.11 The incidence of pulmonary toxicity from amiodarone is not precisely known, but it is estimated to be 1•5%.11 Although the association of PPFE with amiodarone has not yet been described, given the amount of lung toxicity cases induced by amiodarone, the multiplicity of clinical presentations observed, added to the description of PPFE as a possible pattern associated with lung toxicity induced by drugs, sustain the hypothesis that PPFE can be the expression of lung toxicity induced by amiodarone. Moreover, the symptom regression after the amiodarone suspension and the absence of radiologic changes before the amiodarone prescription support the hypothesis of the association between PPFE and amiodarone intake in this clinical case.