Mojo picon is a typical sauce from the Canary Islands, made from oil, vinegar and red pepper, which gives it its characteristic red color. This spicy sauce, used in the olden days by sailors on the high seas to accompany our famous papas arrugadas - wrinkled potatoes - when there was nothing else to eat, is the product of the meeting of different cultures at a time when our islands were a bridge for trade between the Americas, Europe and Africa. Nowadays, when someone from Canary Islands travels abroad, they are immediately associated with this dish, which could almost be seen as their “calling card”. This cultural sauce pot has had its impact not only on gastronomy, but also on the patients of this autonomous community.

Although the Canarian population is considered to be phenotypically Caucasian, their ethnic origins differ from the rest of Spain. The inhabitants of the archipelago are descendants of a mixture of an aboriginal population from northern Africa and European settlers who arrived in the islands in the 15th century.1 Factors such as the distance from the continent and the geographical features of the islands themselves led to a tendency towards endogamy over many generations. This, in turn, led to the emergence of rare diseases in specific areas of the region, for example, familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy2 or rare allele variants in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.3 The result of this “genetic selection” is that chronic pathologies such as cardiovascular or respiratory diseases may present in more complex forms in inhabitants of the Canary Islands than in the continental population.1,4

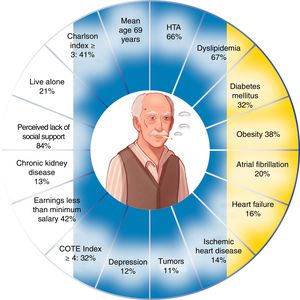

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), for example, is less prevalent in the Canaries than in the rest of Spain,5 although several studies seem to suggest that it is more difficult to manage.6,7 Patients in the Canaries have a greater comorbidity burden than other Spanish cohorts with a similar degree of obstruction,6 complicating their clinical situation. Despite a lower tobacco consumption, these patients show a high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidity, even at earlier disease stages; reported rates are higher than those described in Spain in general,7 in Europe, and in the United States. Of particular interest are a greater presence of hypertension (HT), dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiac arrhythmia, and ischemic heart disease (IHD) (Fig. 1).

Most individuals are prompted to seek medical attention because of dyspnea. This symptom encompasses multiple qualitative and quantitative parameters, and as a result, is manifested in this disease in several different ways. The important role of cardiovascular comorbidities in COPD must also be taken into account. In the Canary Islands, the most symptomatic COPD patients (GOLD 2017 groups B and D) have a 4-fold risk of IHD or heart failure (HF), and a 2-fold risk of cardiac arrhythmia, diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2), HT and peripheral artery disease.8 These results differ from observations reported in other populations: Kahnert et al.9 found that in COPD in the United Kingdom, the most symptomatic patients had a risk of IHD of less than 2-fold, and that the risk of HF, DM2, or HT remained non-significant. These results underline the importance of evaluating cardiovascular disease when monitoring symptoms in Canary Islanders, and highlight the risk of heart disease in subjects with a greater degree of dyspnea and cerebrovascular accident in patients with increased probability of exacerbation.10

With regard to the risk of hospitalization, results obtained in the Lung Health Study11 showed that up to 42 % of first hospitalizations in patients with mild COPD were due to cardiovascular causes. This must be seen in the light of the results of the SUMMIT study, which determined that the risk of a cardiovascular event after an exacerbation in COPD patients with cardiovascular comorbidity increased by 4-fold in the 30 days after onset, and was as high as 10-fold in patients requiring admission to hospital.12 A small population-based study conducted in the Canary Islands evaluating the effectiveness of the administration of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate polysaccharide vaccination in COPD patients with established cardiovascular disease found that the risk of hospitalization for exacerbation in subjects with cardiovascular comorbidity increased up to 9-fold compared to those who did not present this pathology.13 Due to the high cardiovascular burden of patients in our islands, these data reinforce the need to establish measures to improve the monitoring of comorbidities and to maximize follow-up in the event of exacerbation.

With regard to the impact of comorbidities on the life expectancy of these patients, a study published by Divo et al.14 concluded that cardiovascular disease, especially IHD, HF, or cardiac arrhythmia, has a negative impact on the survival of patients with COPD in outpatient follow-up. On the basis of the results of that study, we performed a similar analysis in patients in the Canary Islands, and found that the impact of cardiovascular disease differs from the findings of those authors, yet chronic kidney disease acquired a special relevance in the community of the Canaries. No significant impact was detected for the presence of IHD,15 but this may be because this disease is closely and efficiently managed in the archipelago.

The factors discussed here should lead us to reflect on the differences between the COPD population in the Canary Islands and the Iberian peninsula or Europe, and to bear in mind the specific particularities of our patients. Just like our wrinkled potatoes with spicy sauce, this COPD population has its own identity marked by the complexity of its patients, in which the cardiovascular comorbidity/systemic involvement (what we have colloquially dubbed “the Canaries phenotype”) plays a significant role, and where the combination of hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM2, smoking and obesity is part of our day-to-day experience. Given these facts, then, we must be aware of the need for targeted measures aimed at the correct management of these patients with the goal of improving their quality of care.

My thanks go to all my colleagues and friends who have supported me in my efforts to characterize the COPD population in the Canary Islands, and I also thank Violeta Ferrer for her illustration.

Please cite this article as: Figueira Gonçalves JM. Patología cardiovascular en el paciente con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica de las islas Canarias. «El mojo picón de nuestras papas». Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:57–58.