We report the case of a 56-year-old man, former smoker, with a history of dyslipemia, gastroesophageal reflux, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, referred from another hospital for investigation of progressive interstitial disease. He had been employed as a firefighter and a farm worker. He had contact with chickens and also had a feather sofa. No significant family history was reported.

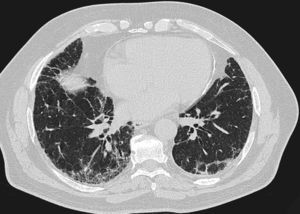

One year previously, he had presented with pleuritic central chest pain, fever, dry cough, and progressive dyspnea, initially thought to be idiopathic pulmonary disease. All possible sources of domestic exposure were ruled out, and the patient was treated with prednisone 30mg/day for 3 months, and then with N-acetylcysteine 1800mg/day, but continued to deteriorate clinically. On physical examination, crackles were heard on lung auscultation and nail clubbing was noted. Autoimmune markers were normal. The only significant finding was raised anti-Aspergillus fumigatus and anti-Penicillium spp. IgG antibodies. Lung function testing showed forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1) of 62%, forced vital capacity (FVC) 62%, FEV1/FVC ratio of 76%, generally reduced lung volumes, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide of 54%. He had moderate hypoxemia and normocapnia. In the walk test, he achieved 600m, with oxygen saturation falling to 87%. Computed tomography showed a pattern inconsistent with usual interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 1). Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed, revealing cellularity and predominant neutrophils. Cryobiopsy was also obtained from the right basal segment. Histology examination showed pulmonary parenchyma with predominantly reactive interstitial histiocytosis suggestive of hypersensitive pneumonitis.

High-resolution computed tomography of the chest showing subpleural reticular opacities with traction bronchiectasis and subpleural honeycombing images, mainly in the lower lobes. No evaluable air trapping is seen in the sections on expiration. These images suggest a pattern consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia (according to the ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT consensus criteria on the diagnosis and management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, 2011).

We suspected that some contact element was causing the clinical picture, so feathers from the sofa were cultivated and Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated. The case was diagnosed as chronic hypersensitive pneumonitis (HP), caused by exposure to this mold. Treatment began with prednisone 30mg/day, and exposure to the antigen was eliminated. Clinical and functional improvement occurred within a few months.

DiscussionThis is the first reported case of HP caused by exposure to the feather stuffing of a sofa colonized by Aspergillus fumigatus.

Differential diagnosis between advanced chronic HP and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is difficult and can only be achieved by intensive investigation of potential exposure to antigens.1,2 Some molds (Aspergillus, Acremonium, Alternaria, Beuvaria, Curvularia, Paecilomyces and Penicillium) synthesize keratinases, which degrade keratin in feathers.3 If the clinical picture is compatible, the presence of disease should be considered in patients with raised IgG antibodies to these antigens.4,5 In our case, anti-Aspergillus fumigatus IgG levels were very high, and as this mold was found in an element to which the patient was continually exposed, this antigen was assumed to be the principal cause of HP and worsening symptoms.

In conclusion, diagnosis was possible in this case due to detection of the source antigen by culture of feathers from the patient's sofa. This experience may be useful in patients with preciptin reactions positive for molds and suspected HP, for whom no other exposure is detected in their case history.

FundingThis study did not receive funding of any type.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Hernandez-Gonzalez F, Xaubet A, Sellarés J. Hongos queratinolíticos en el relleno de plumas de un sofá: una causa poco frecuente de neumonitis por hipersensibilidad. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:474–475.