In 2009, a new influenza A (H1N1) virus of swine origin emerged to cause human infection in the form of acute respiratory disease.1 By August 2010, more than 214 countries, communities and territories had reported laboratory-confirmed cases of influenza A (H1N1) infection, including 18449 deaths.2 Today, influenza A (H1N1) remains one of the main causes of seasonal epidemics.3

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive bacterium that forms part of the normal flora of the skin and the respiratory and intestinal tracts. However, it is an opportunistic pathogen that causes a large number of diseases, including respiratory infections,4 and is one of the major causes of nosocomial infection and infections associated with mechanical ventilation. In recent years, methicillin-resistant strains (MRSA) have become a challenge due to their difficult therapeutic management.5

Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1, HSV-2) cause acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome, and are associated with high morbidity and mortality.6 Although it usually affects immunocompromised patients, cases have also been observed in immunocompetent individuals, developing as a primary infection or reactivation of a latent infection.7 Reports of coinfection with these 3 microorganisms in immunocompetent patients are very rare.8 We report the case of a patient seen in our hospital.

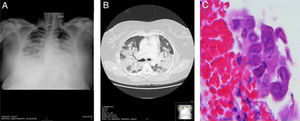

A 41-year-old woman, with no significant history, attended the emergency room with a 4-day history of fever, cough, bloody sputum, and dyspnea at rest. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 39.3°C; BP 100/50mmHg; pulse 101bpm. Of note on pulmonary auscultation were bibasilar crackles reaching the mid-fields. No other significant findings were noted. Clinical laboratory test results showed leukopenia with left shift, raised transaminases, and respiratory failure. Chest X-ray revealed extensive areas of bilateral lung disease, with air bronchogram in the right lung. (Fig. 1A). Chest computed tomography showed extensive pulmonary consolidation in both upper lobes and in the upper segments of the lower lobes, containing air bronchogram (Fig. 1B). The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit where she was intubated and mechanically ventilated. The bronchoalveolar lavage culture and polymerase chain reaction of bronchial secretion were positive for MRSA (>104CFU/ml) and influenza A (H1N1), respectively. During fiberoptic bronchoscopy, a biopsy was obtained from an infiltrating lesion observed in the entry to the middle lobe that showed extensive inflammatory changes with areas of ulceration. The report described abundant squamous cells with large, occasionally multiple, nuclei, with blurred chromatin (ground glass effect), and occasional isolated eosinophilic inclusions, consistent with HSV-1 infection (Fig. 1C), subsequently confirmed by polymerase chain reaction. Treatment was tailored to the antibiotic susceptibility test results (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and levofloxacin), and oseltamivir and acyclovir were added. The patient's progress was favorable, chest X-ray normalized, and she was discharged a few weeks later.

(A) Chest X-ray in decubitus position showing extensive areas of bilateral consolidation. (B) Chest computed tomography showing extensive lung consolidation containing air bronchogram. (C) Bronchial biopsy specimen showing squamous cells with enlarged, occasionally multiple, nuclei, with blurred chromatin (ground glass effect), typical of herpes virus infection (H.E. 400×).

This was a case of pneumonia caused by coinfection of 3 microorganisms (influenza A [H1N1], MRSA, and HSV-1), meeting the diagnostic criteria of each entity.6,8,9 Since the 2009 pandemic, the wider availability and improved yield of tests for early diagnosis have led to a greater number of influenza A infections being documented in immunocompetent patients.10 Epidemics caused by this virus can infect up to 20% of the population, and cause significant morbidity and mortality in affected patients. The presence of concomitant bacterial pathogens leads to an increase in hospital admissions and mortality with a worse prognosis in all cases.11 An association between infection with influenza and bacterial infection was established during the first influenza pandemic of 1918. The mechanism of this association has not yet been clarified, although different theories have been proposed to explain increased susceptibility to this coinfection, including: alteration of the epithelial cells by viral infections that would enhance exposure to certain bacterial ligands; the involvement of neuraminidase in increasing bacterial adhesion, promoting susceptibility to these infections; or damage of the innate immune function by the influenza infection, preventing the elimination of bacteria to the respiratory tract.9 Various studies have analyzed the frequency of certain bacterial species in coinfections. One of the most notable is MRSA with a prevalence of 8.1%.12 In the absence of skin infection, hemorrhagic or necrotizing pneumonia, and in view of our patient's favorable progress after starting treatment, Panton–Valentine leukocidin-positive MRSA infection was reasonably ruled out, although this was not confirmed microbiologically.

An increase has been observed in recent years in the incidence of HSV-1 infection in immunocompetent patients admitted to critical care units receiving prolonged intubation. It has been suggested that orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may prompt the reactivation of HSV-1 in the lower respiratory tract of these patients.13 It is unknown whether the HSV-1 isolated in the respiratory tract is due to oropharyngeal contamination, local viral reactivation, or real HSV-1 bronchopneumonia. The presence of gross lesions in the lips, mouth or bronchi, along with HSV-1 isolated from the pharyngeal mucosa are risk factors for bronchopneumonia caused by this virus.14 Diagnosis is confirmed by serology (IgG and IgM antibodies), or by polymerase chain reaction. The prognosis of the disease depends on the immune status of the patient and underlying predisposing factors (need for mechanical ventilation, chronic diseases, age, etc.).15

In summary, the take-home message from this case is that a single pathogen is not always responsible for a respiratory infection. It can be difficult to identify a patient who presents with a coinfection because the symptoms of all of these entities are similar. Factors such as clinical progress after starting treatment and the presence of risk factors for certain pathogens are key to raise clinical suspicion, to require additional examinations to establish a diagnosis, and to initiate the appropriate treatment as early as possible.

Please cite this article as: Pereiro T, Lourido T, Ricoy J, Valdés L. Coinfección por virus Influenza, virus herpes simple y Staphylococcus aureus resistente a meticilina en una paciente inmunocompetente. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:159–160.