We read with great interest the recent letter to the editor from Lizarzábal Suárez et al.1 describing the case of a 19-year-old man who aspirated liquid paraffin during a fire-eating act. The patient developed lipoid pneumonia, and chest computed tomography showed three cavitary lesions in the pulmonary parenchyma.

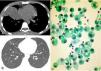

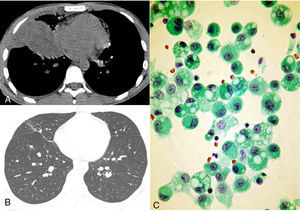

We would like to highlight the findings from a similar case recently encountered. A 26-year-old man was admitted with dyspnea, cough, fever (39°C), and chest pain. Two days before admission, he had accidentally aspirated liquid paraffin during a fire-eating act. Blood count revealed elevated white blood cells, with a leftward shift. Other laboratory data were unremarkable. Computed tomography demonstrated a heterogeneous mass in the right lower lobe, adjacent to the pleural surface (Fig. 1A). Bronchoscopy revealed inflamed, hyperemic bronchial mucosa without purulence or evidence of necrosis. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid showed numerous lipid-laden macrophages (Fig. 1C). The patient was treated with systemic steroids and antibiotics. Computed tomography performed 2 weeks after admission showed remarkable improvement, with reabsorption of the mass, leaving residual scarring (Fig. 1B).

(A) Computed tomography with the mediastinal window setting shows a mass in the right lower lobe, adjacent to the pleural surface. (B) Follow-up computed tomography with the lung window setting demonstrated reabsorption of the mass, with residual scarring. (C) Alveolar macrophages recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage. The cytoplasm is full of large rounded vacuoles that displace nuclei to the periphery.

Fire eater's pneumonia (FEP) is caused by the accidental acute aspiration of hydrocarbon products during a fire-blowing act.2–4 The performer blows a mouthful of liquid hydrocarbon against a burning stick, thereby creating an aerosol that ignites around the stick.5 If aspirated, these hydrocarbons can diffuse rapidly throughout the bronchial tree, inducing bronchial edema, tissue damage, and surfactant destruction. As a consequence, the compounds provoke macrophage activation and cause a local inflammatory reaction.2,4

The diagnosis of FEP is reached by carefully evaluating the patient's anamnesis and clinical characteristics. Symptoms at presentation include cough, dyspnea, fever, and chest pain after hydrocarbon aspiration.2,3 The diagnosis can also be confirmed by the presence of lipid-laden macrophages in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in the context of recent exposure to volatile hydrocarbons.2,4 Tomographic findings in patients with FEP include unilateral or bilateral lung consolidation, with or without low attenuation caused by lipid density or necrosis,4 well-defined nodules, pneumatoceles (well-defined cavitary nodules), pleural effusion, and spontaneous pneumothorax.2 The lesions commonly involve both lower lobes.4

FEP is a pseudo-infectious lung disease characterized by the intense release of inflammatory cytokines. The use of steroids is controversial, but this treatment may improve the outcome in severely affected patients. Prophylactic antibiotics seem to be of benefit, as fever and an elevated leukocyte count can occur and may indicate associated bacterial pneumonia.2,4 Most patients with FEP experience complete recovery within weeks. However, complications such as pulmonary abscess, effusion, bronchopleural fistula formation, and bacterial superinfection may develop.3,4 In conclusion, FEP should be included in the differential diagnosis of pneumonias. Clinical diagnosis is based on recent exposure to volatile hydrocarbons, as symptoms and imaging findings are nonspecific.

Please cite this article as: Marchiori E, Soares-Souza A, Zanetti G. Neumonía del tragafuegos: el papel de la tomografía computarizada. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:282–283.