Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a type of chronic fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of unknown cause with a radiological/histological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).1 IPF can occur in combination with centrilobular and paraseptal emphysema in the upper lobes,2 and 12% of patients present pneumothorax. Bronchopleural fistulae (BF), communications between the pleural space and the bronchial tree, can be a result of previous pleuroparenchymal changes. They represent a therapeutic challenge due to high associated morbidity, and the best approach is individualized treatment.3

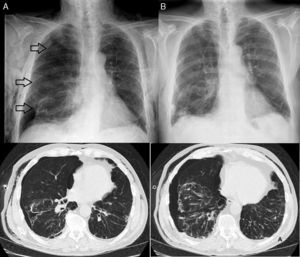

We report the case of a 67-year-old man with a history of hydropneumothorax due to pulmonary contusion and spontaneous pneumothorax, diagnosed with IPF (combined fibrosis/emphysema syndrome subtype) according to ATS/ERS 2011 clinical, radiological and functional criteria,1 treated with pirfenidone. He consulted due to chest pain, sudden onset dyspnea, with the use of accessory muscles of respiration. Examination showed loss of vesicular breath sounds in the right hemithorax, and the findings of a radiographic study were compatible with tension pneumothorax (Fig. 1A). After placement of a chest tube, the patient was transferred to the hospital ward, where a pleural space with persistent air leak was observed, despite 3 endothoracic drainage procedures (2 with fine caliber tube, 8 and 10F, and another with thick caliber tube, 24F) with no resolution of the pneumothorax.

Surgery was ruled out due to the high surgical risk posed by his parenchymal disease, so flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FFB) was performed on day 21 of hospitalization, under deep sedation (patient in semi-sitting position), using a 24G chest tube in the right hemithorax with water seal to identify the absence/presence of air leak. No endoscopic changes were found in the right bronchial tree. The lateral subsegmentary bronchus (SB) of the middle lobe bronchus was accessed, which on detailed examination of the results of a computed axial tomography (CAT) scan appeared to be the origin of the air leak. A Fogarty catheter® was then used to completely collapse the SB, revealing absence of air leak. Two ml of cyanoacrylate were then instilled into the bronchus, guided by telescopic catheter, with no immediate complications. On completion of the FFB, the air leak was intermittent and progressively resolving, and no pneumothorax was observed on the chest radiograph obtained before discharge, 16 days after the procedure (Fig. 1B).

No consensus guidelines are available on the appropriate treatment of these patients. Therapeutic options range from surgery to interventional FFB with the use of different glues, coils, and sealants.3,4 The use of cyanoacrylate, a tissue glue widely used in clinical practice, initially seals the air leak and then subsequently induces an inflammatory response causing fibrosis and proliferation of the mucosa, which seals the leak permanently.

Other possible therapeutic options in this case could have included the use of silver nitrate (glue commonly used in rigid bronchoscopy for sealing fistulae with air leak at the surgical site), Watanabe® spigots (silicon cylinders with small rounded extensions that can be anchored in the bronchus and which rarely migrate), or endobronchial valves (removable, well tolerated, with few known complications, that do not rule out subsequent surgical intervention).4,5 Nowadays, interventional FFB is proposed as an alternative treatment for many airway diseases that were conventionally the preserve of thoracic surgery.

Please cite this article as: de Vega Sánchez B, Roig Figueroa V. Tratamiento endoscópico con cianoacrilato de fuga aérea persistente por fistula bronco-pleural en paciente con fibrosis pulmonar idiopática. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:164–165.