The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among patients with a new diagnosis of lung cancer (LC) is 40%–70%. Both underdiagnosis of COPD and absence of treatment are common in these patients,1–3 and in curable cases these factors influence the choice of surgery or radiation therapy to treat LC, and affect tolerance to chemotherapy and radiation therapy.1,3 International LC guidelines recommend smoking cessation and respiratory rehabilitation, but do not make any explicit statements on intensive, short-term COPD treatment other than those given in the specific COPD guidelines.

Our aim was to study functional improvement of COPD in patients with LC after treatment with double bronchodilation (DBD) with a long-acting beta-adrenergic agent (LABA) and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA). We conducted this prospective study in a population of outpatients seen in a lung cancer rapid diagnosis unit with spirometry performed on their first day in this unit showing forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio <70% and a post-bronchodilator predicted FEV1 <80%. Patients who were already receiving DBD treatment and those with an alternative diagnosis of bronchial asthma were excluded. The effect of DBD on lung function was evaluated at 4 weeks. The choice of the LAMA and the LABA were selected according to medical criteria and the ability and capacity of the patient to follow the treatment. Participants receiving inhaled corticosteroids before inclusion continued to receive this therapy. During this period, all other laboratory, endoscopic and imaging tests required for diagnosis, staging, and multidisciplinary therapeutic decision-making were also performed. At 4 weeks, before LC treatment in all cases, spirometry was repeated to evaluate the impact of DBD on FEV1 and FVC.

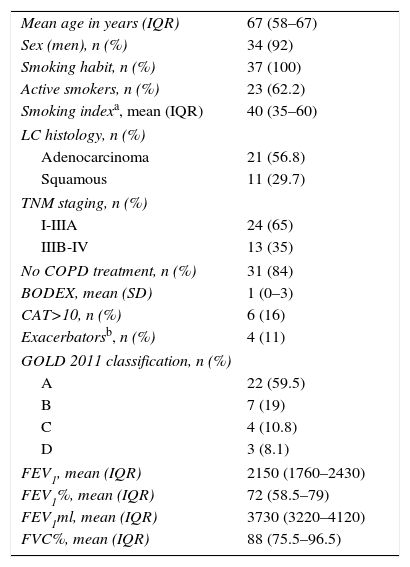

ResultsThirty-seven patients with LC and COPD were included; patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Six had a previous diagnosis of COPD and were receiving bronchodilator treatment, none of which was DBD-based; 4 of these were fluticasone combined with salmeterol. The most commonly used LABA was indacaterol (83.8%), followed by salmeterol, vilanterol, and olodaterol. The most commonly used LAMA was glycopyrronium (51.4%), followed by aclidinium and tiotropium. After 4 weeks of DBD treatment, FEV1 increased by 200ml (interquartile range [IQR] 40–320) and 8% (IQR 9–11) and FVC by 290ml (IQR 75–665) and 6.5% (IQR 1.5–14) on average with respect to baseline values. In 40% of patients, FEV1 and/or FVC increased by 400ml or more, although no response predictors or differences in LC staging were detected on a multivariate analysis. In 5 of the 10 potentially resectable patients who initially presented poor lung function, improvements in FEV1 and FVC after DBD permitted surgical resection for LC to be performed without the need for an oxygen consumption test.

Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics.

| Mean age in years (IQR) | 67 (58–67) |

| Sex (men), n (%) | 34 (92) |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | 37 (100) |

| Active smokers, n (%) | 23 (62.2) |

| Smoking indexa, mean (IQR) | 40 (35–60) |

| LC histology, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 21 (56.8) |

| Squamous | 11 (29.7) |

| TNM staging, n (%) | |

| I-IIIA | 24 (65) |

| IIIB-IV | 13 (35) |

| No COPD treatment, n (%) | 31 (84) |

| BODEX, mean (SD) | 1 (0–3) |

| CAT>10, n (%) | 6 (16) |

| Exacerbatorsb, n (%) | 4 (11) |

| GOLD 2011 classification, n (%) | |

| A | 22 (59.5) |

| B | 7 (19) |

| C | 4 (10.8) |

| D | 3 (8.1) |

| FEV1, mean (IQR) | 2150 (1760–2430) |

| FEV1%, mean (IQR) | 72 (58.5–79) |

| FEV1ml, mean (IQR) | 3730 (3220–4120) |

| FVC%, mean (IQR) | 88 (75.5–96.5) |

CAT: COPD Assessment Test; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; IQR: interquartile range; LC: lung cancer.

In this pilot study, we observed a notable improvement in lung function among patients with a diagnosis of COPD and LC who received DBD, allowing curative surgical interventions in a high percentage of patients.

In a study with a similar objective to ours that also explored postoperative pulmonary complications in 2 intervention groups who received DBD (formoterol+tiotropium) alone vs DBD+budesonide found comparable improvements to those described in our series in both groups, while the group that received budesonide had significantly better outcomes, including fewer postoperative complications.4 A lower incidence of postoperative complications was observed in another study of patients treated with tiotropium.5 In our study, we also found significant improvements in patients with severe COPD, in whom a small improvement in lung function can be decisive in the choice of a treatment, making surgery possible in half of the initially inoperable cases. Despite the obvious benefits of intensive bronchodilator therapy in patients with LC and COPD, no specific evidence-based recommendations are available. If we take into account the limitations of this study, namely, small sample size, lack of a control group and adjustment for the possible benefit of other treatments, our results may justify the conduct of other larger studies to clarify the benefit of DBD in the treatment and prognosis of these patients.

Please cite this article as: Leiro-Fernández V, Priegue Carrera A, Fernández-Villar A. Análisis de la eficacia de la doble broncodilatación (LABA+LAMA) en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) y cáncer de pulmón. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:622–623.