Home oxygen therapy has a great impact on the lives of patients and their families. The aim of this study is to define the opinions, perceptions and attitudes of patients and their caregivers regarding home oxygen.

MethodQualitative, phenomenological study of a sample of 57 subjects, consisting of 18 family members and/or caregivers and 39 patients receiving home oxygen in urban centers. Five focus groups were formed between March and July 2014 in hospitals in Barcelona, Madrid and Alicante. Prior informed consent was obtained from patients and families. The study material consisted of audio recordings of all focus group interviews, transcription of selected materials and field notes. Data analysis was performed using constant comparison method, establishing 2 levels of analysis.

ResultsData from the focus groups were analyzed on 2 levels. A first level of analysis gave 21 categories. In a second level of analysis, these were integrated into 6 meta-categories: care provided by health professionals, psychological impact, care provided by commercial companies, impact on daily life, problems and satisfaction.

ConclusionsHome oxygen has a major psychological impact on the daily lives of both patients and their families, and can cause social isolation. Although the results show that healthcare professionals are highly appreciated, better coordination is needed between different levels of care and companies supplying oxygen in order to provide patients and families with consistent information and useful strategies.

Las terapias respiratorias a domicilio suponen un gran impacto en la vida del paciente y de sus familiares. El objetivo de este estudio reside en conocer las opiniones, percepciones y actitudes de los pacientes y sus cuidadores sobre la oxigenoterapia domiciliaria.

MétodoEstudio cualitativo-fenomenológico de una muestra de 57 personas: 18 familiares y 39 pacientes que reciben oxigenoterapia domiciliaria en núcleos urbanos relevantes. Se realizaron 5 grupos focales entre marzo y julio de 2014 en centros hospitalarios de Barcelona, Madrid y Alicante. El material de análisis constó de las grabaciones en audio de las entrevistas en los grupos focales, la trascripción de las mismas y las notas de campo registradas. El análisis de los datos se realizó a partir del método de las comparaciones constantes.

ResultadosLos datos se analizaron en 2 niveles. En un primer nivel de análisis se obtuvieron 21 categorías que, posteriormente, en un segundo nivel de análisis, se integraron en 6 metacategorías: atención facilitada por los profesionales sanitarios, impacto psicológico, atención facilitada por las casas comerciales, impacto en la vida cotidiana, inconvenientes y satisfacción.

ConclusionesLa oxigenoterapia domiciliaria tiene un gran impacto psicológico y en la vida diaria tanto de los pacientes como de sus familiares. Por otro lado, sería conveniente mejorar la coordinación entre los diferentes niveles asistenciales y las empresas suministradoras de oxigenoterapia para facilitar información coherente y estrategias útiles para los pacientes y familiares.

The ultimate goal of healthcare is to propose interventions that increase value for patients. A simple formula to identify this value, proposed by Porter,1 is the ratio between outcomes and cost, with the focus on aspects of concern to the patient. Although patient satisfaction is traditionally assessed in relation to the care received, this approach is biased because perceptions of quality by persons without medical training may focus on less important aspects, such as satisfaction according to current health status (which yields little information regarding improvement) or according to subjective preferences.2

The Beryl Institute3 defines the patient experience as “the sum of all interactions, shaped by an organization's culture, that influence patient perceptions across the continuum of care”. The areas in which patient experience has greatest impact4 are considered to be health system integration, care coordination, end-of-life care, medication reconciliation and emergency care management. Medication reconciliation and emergency care management, in particular, have a great impact on outcomes and costs. The interest in patient perspectives is in line with the notion of patient-reported outcome measures.5

In the healthcare sector, the right to choose is exercised through personal autonomy and informed consent.6,7 In general terms, encouraging patients to become involved in decisions about their health is crucial.3,4 Evaluating the patient experience—as a way to introduce improvements in medical care—requires a systematic approach to all patient interactions with the healthcare system.

Home respiratory care8 encompasses a set of varied treatments with certain common characteristics, in particular, the participation of various individuals, the great impact on patient and caregiver lifestyles, and (almost invariably) lifelong use. Although use of home respiratory care9 has been recognized for many years to be frequently inappropriate, no data are available that point to the role of the patient in choosing alternatives. The best results would be achieved by combining objective criteria with patient circumstances and preferences. Wise et al.10 summarize this notion, and highlight the need for care packages adapted to the requirements of each patient and the availability of local resources.

The aim of this study was to collect information on the opinions, perceptions and attitudes of patients and their caregivers regarding home respiratory care, specifically, home oxygen therapy (HOT).

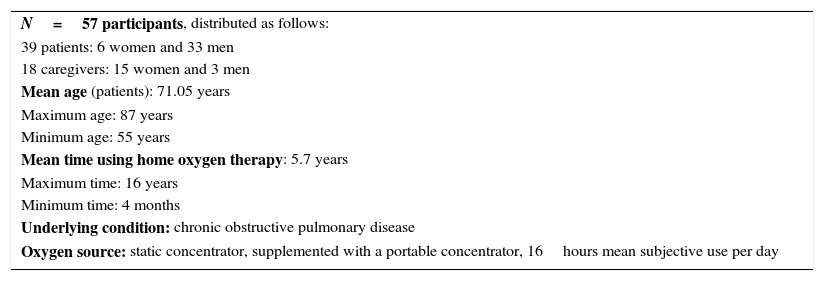

Material and MethodsStudy SampleTen patients receiving HOT were each selected from 2 hospitals in Barcelona, 2 hospitals in Madrid and 1 hospital in Alicante, for a total sample of 50 patients. The patients were selected, not as a statistically representative sample, but directly by pulmonologists—members of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR)—on the basis of the relevance of each case. Unlike quantitative methods (based on probability sampling to ensure randomness), qualitative methods based on purposive sampling seek to describe and understand individual cases11 as a potential source of detailed information and insights regarding the subject of study. The main goal is not measurement but understanding a phenomenon in all its complexity.12 The criteria used to select patients from the database of each hospital were as follows: a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), use of static-source and portable HOT equipment, ability to attend appointments either independently or with the assistance of a caregiver (a family member or other helper), signed informed consent and actual attendance at interview. A total of 50 patients were contacted by telephone, resulting in 57 individuals—39 patients and 18 caregivers—finally attending interviews (Table 1).

Sample Characteristics.

| N=57 participants, distributed as follows: |

| 39 patients: 6 women and 33 men |

| 18 caregivers: 15 women and 3 men |

| Mean age (patients): 71.05 years |

| Maximum age: 87 years |

| Minimum age: 55 years |

| Mean time using home oxygen therapy: 5.7 years |

| Maximum time: 16 years |

| Minimum time: 4 months |

| Underlying condition: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Oxygen source: static concentrator, supplemented with a portable concentrator, 16hours mean subjective use per day |

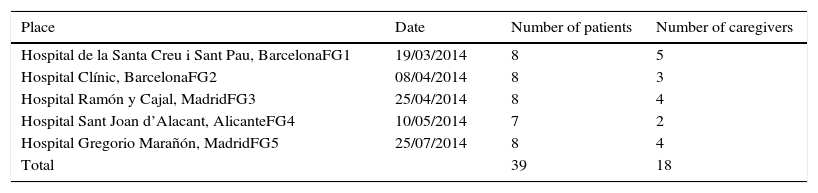

A phenomenological approach was adopted for this qualitative study aimed at collecting information on the experiences, opinions, beliefs and values of patients and caregivers. Data collection was through focus group interviewing, a technique that encourages disclosure of experiences, opinions, beliefs, emotions and values.11 Fieldwork was conducted between March and July 2014 in 5 hospitals in Barcelona, Madrid and Alicante (Table 2). Contributors are listed in Appendix 1.

Focus Group (FG) Descriptions.

| Place | Date | Number of patients | Number of caregivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, BarcelonaFG1 | 19/03/2014 | 8 | 5 |

| Hospital Clínic, BarcelonaFG2 | 08/04/2014 | 8 | 3 |

| Hospital Ramón y Cajal, MadridFG3 | 25/04/2014 | 8 | 4 |

| Hospital Sant Joan d’Alacant, AlicanteFG4 | 10/05/2014 | 7 | 2 |

| Hospital Gregorio Marañón, MadridFG5 | 25/07/2014 | 8 | 4 |

| Total | 39 | 18 |

After obtaining the informed consent of participants, focus group sessions were conducted, digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each session lasted 60min on average. The transcripts were 12 pages long on average, giving a total of 72 pages of information for analysis.

To encourage communication and establish a climate of trust, at the beginning of each session participants were informed of the purpose and aims of the study, and were guaranteed anonymity and data confidentiality. Participants were also told that they could leave at any time during the sessions with no explanation.

The sessions began with very open, non-directive questions intended to create a climate of calm and trust. The notation system used to identify transcript fragments is exemplified as follows: “P1/F1 FG1”, where “P” means patient, “F” means family member/caregiver and “FG” means focus group, with unique numbers identifying participants (whether patient or family member/caregiver) and focus groups.

Data AnalysisQualitative research analysis is characterized by the implementation of various operations at the conceptual level that identify meaningful patterns, and by the construction of a framework that communicates what the data reveal.13

The analytical material consisted of:

- -

Audio recordings of all focus group sessions.

- -

Transcripts of selected materials.

- -

Field notes made during the focus group sessions and the analysis process.

The focus group transcripts were analyzed using the constant comparative method in order to identify units of meaning and categories for fragments reflecting the same ideas.14 Data for the 5 focus groups were analyzed at 2 levels that progressively refined and structured the information, as follows:

- •

Level 1: segmentation of information and identification and descriptive categorization of units of meaning.

- •

Level 2: construction of a system of emerging core themes (meta-categories).

ATLAS-ti 5.0 qualitative data analysis software was used for mechanical tasks such as segmentation, separation, sorting and search and retrieval operations.

The initial (level 1) analysis focused on developing descriptions of meanings assigned to HOT by patients and caregivers. A first reading of the focus group transcripts yielded a comprehensive overview of content and the core topics raised. In a second reading, data were segmented into units of meaning based on text fragments with semantic meaning that reflected the same concepts.

The categories were constructed inductively, openly and generatively, and the process concluded when the categories were saturated, i.e., when no further information generating new categories was encountered.

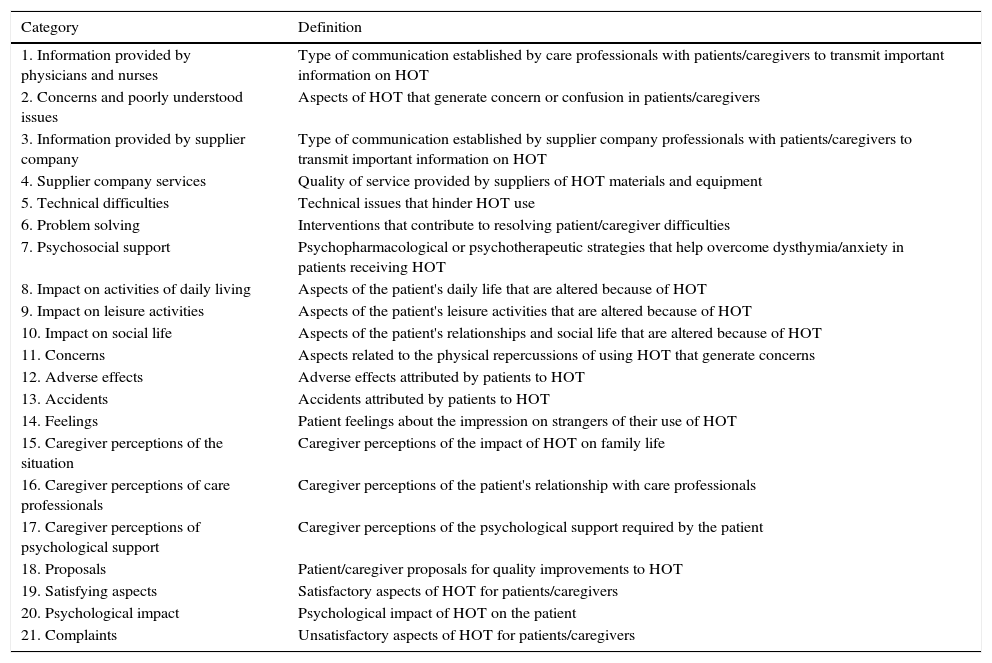

ResultsA total of 283 units of meaning were identified and grouped into 21 categories as listed and defined in Table 3.

Categories Resulting From Level 1 Analysis of The Data.

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1. Information provided by physicians and nurses | Type of communication established by care professionals with patients/caregivers to transmit important information on HOT |

| 2. Concerns and poorly understood issues | Aspects of HOT that generate concern or confusion in patients/caregivers |

| 3. Information provided by supplier company | Type of communication established by supplier company professionals with patients/caregivers to transmit important information on HOT |

| 4. Supplier company services | Quality of service provided by suppliers of HOT materials and equipment |

| 5. Technical difficulties | Technical issues that hinder HOT use |

| 6. Problem solving | Interventions that contribute to resolving patient/caregiver difficulties |

| 7. Psychosocial support | Psychopharmacological or psychotherapeutic strategies that help overcome dysthymia/anxiety in patients receiving HOT |

| 8. Impact on activities of daily living | Aspects of the patient's daily life that are altered because of HOT |

| 9. Impact on leisure activities | Aspects of the patient's leisure activities that are altered because of HOT |

| 10. Impact on social life | Aspects of the patient's relationships and social life that are altered because of HOT |

| 11. Concerns | Aspects related to the physical repercussions of using HOT that generate concerns |

| 12. Adverse effects | Adverse effects attributed by patients to HOT |

| 13. Accidents | Accidents attributed by patients to HOT |

| 14. Feelings | Patient feelings about the impression on strangers of their use of HOT |

| 15. Caregiver perceptions of the situation | Caregiver perceptions of the impact of HOT on family life |

| 16. Caregiver perceptions of care professionals | Caregiver perceptions of the patient's relationship with care professionals |

| 17. Caregiver perceptions of psychological support | Caregiver perceptions of the psychological support required by the patient |

| 18. Proposals | Patient/caregiver proposals for quality improvements to HOT |

| 19. Satisfying aspects | Satisfactory aspects of HOT for patients/caregivers |

| 20. Psychological impact | Psychological impact of HOT on the patient |

| 21. Complaints | Unsatisfactory aspects of HOT for patients/caregivers |

Abbreviations: HOT, home oxygen therapy.

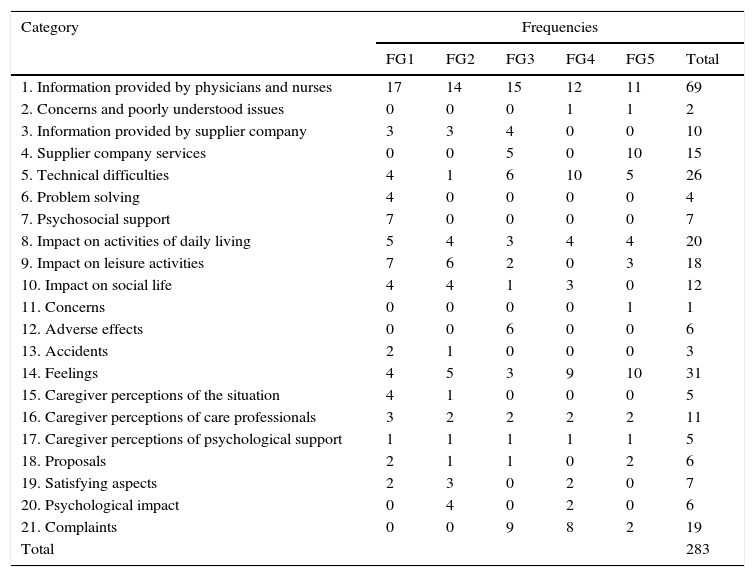

The frequencies of occurrence of the categories in each of the 5 focus groups are summarized in Table 4. The importance of each category could be determined quantitatively from the frequency with which the corresponding topic was mentioned by patients and families compared to the total frequency for all 5 focus groups.

Frequencies by Focus Group (FG) For 21 Categories Resulting From Level 1 Analysis of the Data.

| Category | Frequencies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG1 | FG2 | FG3 | FG4 | FG5 | Total | |

| 1. Information provided by physicians and nurses | 17 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 69 |

| 2. Concerns and poorly understood issues | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3. Information provided by supplier company | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 4. Supplier company services | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 15 |

| 5. Technical difficulties | 4 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 26 |

| 6. Problem solving | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 7. Psychosocial support | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 8. Impact on activities of daily living | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 20 |

| 9. Impact on leisure activities | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 18 |

| 10. Impact on social life | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| 11. Concerns | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 12. Adverse effects | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 13. Accidents | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 14. Feelings | 4 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 31 |

| 15. Caregiver perceptions of the situation | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 16. Caregiver perceptions of care professionals | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| 17. Caregiver perceptions of psychological support | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 18. Proposals | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| 19. Satisfying aspects | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| 20. Psychological impact | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| 21. Complaints | 0 | 0 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 19 |

| Total | 283 | |||||

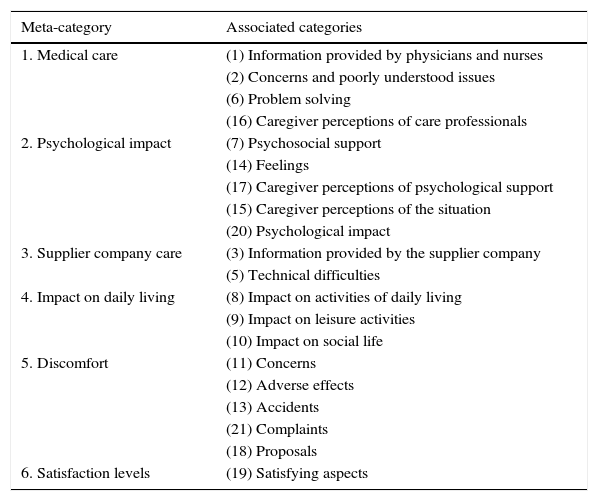

In the level 2 analysis—consisting of a comparison of categories so as to identify structural and theoretical similarities and common elements—the 21 categories that emerged in level 1 were grouped and structured into 6 thematic units or meta-categories. These 6 meta-categories were built simultaneously and interactively as the level 1 categories emerged, as shown in Table 5.

Meta-categories Resulting from Level 2 Data Analysis.

| Meta-category | Associated categories |

|---|---|

| 1. Medical care | (1) Information provided by physicians and nurses |

| (2) Concerns and poorly understood issues | |

| (6) Problem solving | |

| (16) Caregiver perceptions of care professionals | |

| 2. Psychological impact | (7) Psychosocial support |

| (14) Feelings | |

| (17) Caregiver perceptions of psychological support | |

| (15) Caregiver perceptions of the situation | |

| (20) Psychological impact | |

| 3. Supplier company care | (3) Information provided by the supplier company |

| (5) Technical difficulties | |

| 4. Impact on daily living | (8) Impact on activities of daily living |

| (9) Impact on leisure activities | |

| (10) Impact on social life | |

| 5. Discomfort | (11) Concerns |

| (12) Adverse effects | |

| (13) Accidents | |

| (21) Complaints | |

| (18) Proposals | |

| 6. Satisfaction levels | (19) Satisfying aspects |

The 6 meta-categories encompassed 3 broad areas: information, impact on individuals, and problems. Based on these areas, key service delivery aspects were identified, as follows:

- •

Information: Noteworthy were the meta-categories referring to the care provided by both healthcare professionals and by supply companies, where key elements were trust and the need for coordination.

- •

Impact: Especially relevant were the meta-categories referring to psychological impact and impact on daily living, where key elements were systematic support, logistics and organization.

- •

Problems: The salient meta-categories were those referring to discomfort and dissatisfaction, where key elements were responsiveness and evaluation.

The limitations of this study are those of any qualitative research that takes a holistic approach to the study of an everyday reality with a view to generating hypotheses and uncovering unexpected information. Patients were selected by their attending physician, a process that may be open to selection bias. However, qualitative approaches aim to identify common, systematically repeated and unexpected issues, and therefore the effect of sampling bias is minimal. Sampling in qualitative research is not the same as in quantitative research, given that no statistical study is required, nor is there any need to establish causality.

Qualitative research is useful to identify areas requiring specific interventions aimed at improving care, or to pinpoint issues highlighted by patients that require further analysis. In a review of qualitative research studies, Disler et al.15 showed that it was possible to identify—from small groups of patients with advanced COPD—key areas influencing the patient experience, namely, their understanding of the condition, the symptom burden and the psychological impact. In terms of identifying problems or critical elements, qualitative research based on small focus groups or semi-structured interviews yielded similar results for patients with sleep apnoea in qualitative research studies reviewed by Ward et al.,16 who highlighted the impact of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) on social relationships, symptom management and treatment complications and their association with treatment adherence.

Qualitative research does not focus on causal links or specific manifestations, but rather on opportunities to improve the patient experience regarding repeated occurrences of a problem.

The 6 meta-categories are discussed below in terms of salient features.

- 1.

Although overall assessment of the care provided by professionals was generally positive, the study highlighted the fact that information was not always fully assimilated. For instance, different ways of coping with the disease and even of using different HOT equipment raised concerns and questions. There were also differences in the quality of care received by patients participating in, versus patients not participating in, pilot programs.

Structured therapy education is crucial to the management of chronic diseases and especially so in complex circumstances that require HOT. Doherty et al.17 recommend structured therapy education programs as a means to ensure greater treatment adherence, better self-monitoring (spirometry and oxygen saturation values) and better responses to technical complications and decompensations. Our focus group participants also highlighted the role played by nurses and the usefulness of group activities.

- 2.

The psychological impact of the disease and its treatment with HOT, for both patients and families, was noteworthy, although adaptation differed depending on personalities and coping strategies. References to death were rare or only mentioned in terms of clichés (“it comes to all of us”) and there was no evidence of planning in the form of advance healthcare directives or living wills. It is clear that COPD impacts both caregivers as well as patients, and social isolation was one aspect that seems to greatly affect the former.18 The focus groups sessions highlighted important elements for future studies, such as the lack of psychological support, embarrassment at using oxygen in public, and lack of respite facilities to give carers temporary relief from their responsibility whenever possible19 Therapy education programs should also carefully consider adaptation times.

The role played by HOT suppliers has received little attention in the literature. Our focus group sessions highlighted 2 apparently contradictory positions:

- a.

Satisfaction due to direct contact with representatives from the oxygen supply company, who often helped confirm or interpret the information received.

- b.

A general degree of dissatisfaction regarding the support given by commercial oxygen therapy suppliers:

- i.

Distribution was often perceived more as mere delivery than as a service.

- ii.

Consumables did not always meet the needs of patients.

- iii.

Changes in suppliers were perceived as disruptive to maintenance and the provision of supplies.

- i.

Any complaint related to these services needs to be investigated in depth. In our study, these complaints were mainly voiced by patients and their carers domiciled in 2 of the geographical areas in which the study was conducted. The discrepancy in terms of satisfaction highlights the weakness of a satisfaction survey in detecting problems with HOT services. The fact that individuals in different focus groups made complaints suggests the existence of genuine service deficiencies, although not enough information was available to enable us to assess the extent of these deficiencies. A comprehensive study to identify basic HOT service quality issues would be useful, and institutional mechanisms to record problems and propose solutions should be implemented.

- a.

- 3.

The extent to which daily routines, relationships and social activities were affected was highly significant. The limitations imposed by illness and home respiratory care forced a change in habits, particularly in expectations regarding retirement (travel, visits to offspring, socializing, etc.). Mobility issues probably had the greatest impact on patients relying on HOT; air travel in particular is an issue that needs to be addressed.20

- 4.

HOT logically implies discomfort for patients. Kampelmacher21 reported that over 80% of patients have problems related to HOT, with almost 40% reporting nasal problems. One especially worrying issue is safety; 1 patient in our study reported burns when using powercutting tools. Newspaper articles report hazards (http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/jean-booth-e-cigarette-fire-gran-3412824) and even mishaps resulting in death (http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-merseyside-28701515) associated with the use of electronic cigarettes. However, no systematic data has been reported on risk situations and accidents related to the use of HOT. A systematic study in this regard would contribute useful information on risk situations for patients.

- 5.

Regarding satisfaction levels, most dissatisfaction was expressed regarding the cost of the electricity required for the concentrator, no longer funded by the Spanish government. In contrast—and despite criticism of the supplier companies—study subjects acknowledged that prompt action was usually taken in emergency situations. Nonetheless, any assessment of the service overall should be approached from different perspectives, and should both quantify the problem and propose suitable responses to circumstances that hinder treatment.

Any analysis of the patient experience is only meaningful when followed up by action.22 Improvement opportunities identified directly through focus group sessions are an obvious starting point. Focus group information can also identify key issues requiring more extensive surveys. Ultimately, input from patients should be used to design services23 that take their needs and preferences into account.

Although methodological challenges exist regarding evaluation of the patient experience,24 there is no doubt that patient contributions are crucial to overall evaluation of healthcare services, and can even improve clinical safety.25 Poor communications (especially at discharge)—one of the problems identified from analyses of the patient experience26—is generally related to poor service quality. Further exploration of the results of our study in larger samples would give further insight into the patient experience with HOT and other home respiratory care scenarios.

In conclusion, this qualitative study has shown that HOT has a great impact both on the psychological wellbeing and the daily life of patients and their families. Our results also suggest a need to improve coordination between different care levels and HOT supply companies to ensure that patients and their families receive coherent and useful information.

Funding2014/2015 SEPAR Year of the Chronic Patient and Home Respiratory Care.

Authorship- •

Xavier Clèries participated in study design, conducted the 5 focus groups and participated in data analysis and article writing.

- •

Montserrat Solà participated in study design, data analysis and article writing.

- •

Eusebi Chiner participated in study design, data analysis and article writing.

- •

Joan Escarrabill participated in study design, data analysis and article writing.

- •

The 2014/2015 SEPAR Year of the Chronic Patient and Home Respiratory Care Group of Collaborators (Appendix 1) participated in study design and sample selection.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The 2014/2015 SEPAR Year of the Chronic Patient and Home Respiratory Care Group of Collaborators in Patient Experience Evaluation:

Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona): María Rosa Güell Rous, Fátima Morante Vélez.

Hospital Clínic Universitari (Barcelona): Carme Hernández Carcereny, Néstor Soler Porcar.

Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón (Madrid): Liliana Morán Caicedo, José Miguel Rodríguez González-Moro.

Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Madrid): Jose Luis García González, Salvador Díaz Lobato.

Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant (Alicante): José N. Sancho Chust.

SEPAR: Pilar de Lucas Ramos, Estrella Fernández Fabrellas.

Please cite this article as: Clèries X, Solà M, Chiner E, Escarrabill J, en nombre del Grupo Colaborador del Año SEPAR 2014/2015 del Paciente Crónico y las Terapias Respiratorias Domiciliarias para la evaluación de la experiencia del paciente. Aproximación a la experiencia del paciente y sus cuidadores en la oxigenoterapia domiciliaria. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:131–137.

The members of the 2014/2015 SEPAR Year of the Chronic Patient and Home Respiratory Care Group of Collaborators in Patient Experience Evaluation are listed in Appendix 1.