Corticosteroid-dependent asthma is defined as the need for daily administration of oral corticosteroids.1 This definition, however, is ambiguous, since it includes both patients who receive this treatment and experience little improvement, and those who benefit from it (with a varying degree of response). The GOAL study showed that only 7% of patients who were uncontrolled at maximum doses of fluticasone/salmeterol achieved control with an oral steroid regimen.2 Few studies have been conducted in this specific patient group, despite their clinical relevance. We report the case of a patient with corticosteroid-dependent asthma, and review the management and progress of all corticosteroid-dependent asthmatics seen in our specialist clinic (10 of a total of 475 patients).

A 69-year-old woman, non-smoker, with a diagnosis of late-onset, non-allergic asthma, IgE 770kU/l, eosinophils 900/mm3, FENO 31ppb. Asthma was initially poorly controlled with a combination of maximum doses of budesonide/formoterol, as indicated by asthma control test (ACT) 15, a severe exacerbation in the previous year, FEV1 64%, and positive bronchodilator challenge. Significant comorbidities included rhinosinusitis and obesity. Treatment with deflazacort 30mg for 3 weeks increased ACT to 23 and FEV1 to 67%, but when it was withdrawn, ACT returned to 16 and FEV1 to 67%. Tiotropium (18μg/day) was added to the combination of fluticasone/salmeterol (500/50μg), but ACT remained unchanged, while FEV1 rose to 70%. Treatment was subsequently switched to inhaled fluticasone (1000μg/day), tiotropium (18μg/day) and indacaterol (150μg/day). The patient is currently free of exacerbations, her ACT is 24 and FEV1 is 79%.

In our opinion, a patient who is uncontrolled and presents bronchial obstruction despite treatment with a combination of maximum dose inhaled corticosteroids (IC)-long-acting β-2 agonist (LABA) has corticosteroid-dependent asthma. In the case of our patient, her FEV1 normalized (at least to >70%) and ACT rose to ≥20 after 3–4 weeks of treatment with deflazacort 30mg. Subsequently, when the oral corticosteroid was discontinued, her clinical and functional status returned to the previous situation.

Clinical characteristics, treatment, and progress of patients with corticosteroid-dependent asthmaTen of our patients (of 475 regularly seen in our consulting rooms) had corticosteroid-dependent asthma. They were typically middle-aged (49.2±15.1 years), with late onset of symptoms (7/10 cases), intense peripheral eosinophilia (eosinophils 565.0±286.8/mm3), elevated IgE (379.7±357.3kU/l), FENO (31.7±13.2ppb), and significant comorbidities (particularly obesity, rhinosinusitis, and polyposis). Despite the correct use of IC/LABA at maximum doses, these patients remained symptomatic with signs of bronchial obstruction, yet only 2 developed 2 or more severe exacerbations in a period of 1 year. It seems that in most cases, standard treatment can prevent exacerbations, while failing to provide full control of symptoms or normalization of lung function. This was achieved in all cases when an oral corticosteroid was added, although this treatment was unacceptable due to adverse events.

These 10 patients were managed by the same pulmonologist. For the 2 patients in whom severe exacerbations persisted, the treatment strategy consisted, firstly, of adding omalizumab to the regimen. The response of the patients who received omalizumab confirm its efficacy in reducing exacerbations, but also its lack of effect on lung function.3 Persisting bronchial obstruction may explain why optimal control of symptoms is elusive in many patients.

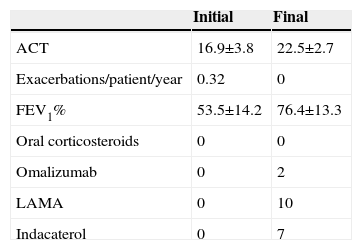

The next step for all patients consisted of adding a long-acting muscarinic antagonist, a medication that has already demonstrated its efficacy in this clinical setting.4 This intervention helped improve patients’ lung function and symptoms, but to an insufficient degree in 7 cases. We decided to add indacaterol to these 7 patients’ regimens: this potent bronchodilator has demonstrated efficacy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but little experience is available in asthma.5 This combined therapeutic strategy resulted in a significant improvement in lung function and symptoms (Table 1) among corticosteroid-dependent asthma patients, while avoiding the use of oral steroids.

Clinical Progress and Treatment Modifications in the 10 Patients Diagnosed With Corticosteroid-dependent Asthma.

| Initial | Final | |

|---|---|---|

| ACT | 16.9±3.8 | 22.5±2.7 |

| Exacerbations/patient/year | 0.32 | 0 |

| FEV1% | 53.5±14.2 | 76.4±13.3 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 0 | 0 |

| Omalizumab | 0 | 2 |

| LAMA | 0 | 10 |

| Indacaterol | 0 | 7 |

ACT: asthma control tests; FEV1%: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; LAMA: long-acting anticholinergics.

Study concept and design, data collection, analysis of results, interpretation of findings, and drafting the manuscript: Pérez de Llano.

Study design and data collection: García Rivero and Pallares.

Data collection: Mengual.

Data analysis and interpretation of results: Golpe.

Conflict of InterestsDr Pérez de Llano has received payment from Novartis, Boehringer, Chiesi, Almirall, Esteve and Ferrer, for presentations at medical congresses, consultancy, and coordination or participation in clinical research projects. He has also been invited to attend national or international congresses by some of these companies.

Please cite this article as: Pérez de Llano LA, García Rivero JL, Pallares A, Mengual N, Golpe R. Asma corticodependiente: nuestra experiencia clínica. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:660–661.