Apert syndrome is a rare variant of craniosynostosis, characterized by premature fusion of the cranial sutures, causing physical and mental health problems in patients from an early age.1 During the course of the disease, patients may develop obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), due to their various craniofacial abnormalities. We present a case of Apert syndrome with OSAS treated satisfactorily with CPAP, which has not been previously reported in the Spanish literature.

A 6-year-old girl, diagnosed with craniosynostosis and sclerodactyly of the hands and feet, who had undergone surgery at the age of 3 for cleft palate and craniostomy, followed up in the pediatric and children's trauma departments. She was referred to the Respiratory Medicine clinic with a report from her teacher saying that in recent weeks she had been falling asleep, not only in class, as was usual, but also at mealtimes, and the food had to be taken out of her mouth after she fell asleep at the table. It was very difficult to keep her awake or to wake her if she had fallen asleep, and on occasions she had even fallen asleep standing up. The mother reported that the child slept a lot but poorly, had snored from birth and slept almost 20h a day, going to bed at 19:00h and waking frequently, with repeated periods of asphyxia.

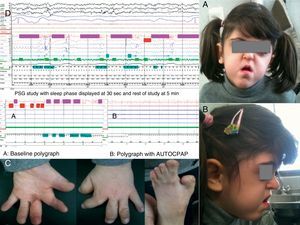

Physical examination revealed short stature, ridging along the cranial sutures, with a advanced coronal suture fused at the join of the orbit, prominent, bulging eyes, underdeveloped midface with maxillary hypoplasia, crowded teeth and high-arched palate (Fig. 1A and B), Mallampati score 4 with no hypertrophy of the tonsils. Scarring secondary to surgery performed at 10 months for syndactyly with membranes and proximal and mid-phalanges fused in the hands, along with pollex varus and hallux varus in the feet (Fig. 1C). The patient was very sleepy throughout the examination and even fell asleep on the chair in the consulting room. A diagnostic polysomnography showed: recording time 534min (m), total sleep time 458.5m, sleep latency 0.5m, sleep efficiency 85.9%, N1 21.2%, N2 73%, N3 5.9%, REM 0%, arousal index 73.2h−1, 669 respiratory events recorded, with 331 predominantly obstructive apneas, apnea and hypopnea index 87.5h−1, 500 snores (10.4%), mean SaO2 86%, minimum SaO2 64% and desaturation index 96.1h−1. The following day CPAP was initiated at 5cmH2O with an oronasal mask, and an appointment was made one week later for adaptation and titration with the hospital auto-CPAP (REMstar Auto Intl Respironics®), connected to the polygraph flow channels, obtaining an apnea and hypopnea index of 5h−1 with pressures between 10 and 15cmH2O, with complete resolution of snoring, and a 90th percentile of 14cmH2O (Fig. 1D).

She commenced treatment with an auto-CPAP, with an oronasal mask due to the high pressures required. Adaptation and compliance was very good. Three months later, the patient showed great clinical improvement: she no longer had daytime sleepiness and was active, able to talk and attend school practically normally, changing the CPAP interface to a nasal mask.

Craniosynostosis can be classified as isolated or syndromic. Within the syndromic presentations, the most common and well-known are Crouzon, Saethre-Chotzen, Pfeiffer and Muenke syndrome, and Crouzon syndrome with ancanthosis nigricans.1 They are caused by a mutation in fibroblast growth factors during the formation of the gametes and alterations in the FGRFR1 and FGRF42 genes in patients with Crouzon, Apert and Pfeiffer syndromes, the TWIST gene in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome and the FGFR gene in Muenke syndrome.1 Transmission is autosomal dominant, but sporadic mutations exist in non-affected parents.1 The incidence is 1.2 per 100000 live births. Apert syndrome is characterized by premature closure of the cranial sutures in a pointed shape, deforming the facial architecture and subsequently producing functional changes with a wide spectrum of clinical variability.1,4 Although it has not been studied in depth, approximately 40% of cases develop OSAS, mainly due to midface hypoplasia,2,3 but it may also be associated with changes in the laryngopharynx or larynx, tracheobronchomalacia and other abnormalities which contribute to OSAS.5 If left untreated, OSAS may lead to sleep fragmentation, recurrent infections, growth and developmental delay, altered cognitive functions, cor pulmonale or sudden death,3 so a polysomnography study4 must be carried out, as must endoscopy of the airways, since obstruction has been observed at several levels.2,3,5,6 Treatment of moderate to severe OSAS in patients with craniosynostosis is complicated and difficult, because CPAP not only must be administered at very high pressures, as in our case, but must also be initiated at an early age, and will probably have to be for life. In addition, adenotonsillectomy may be required, along with orthodontics and maxillary surgery,1,2,3,6 all of which must be adapted in line with the patient's growth.

Please cite this article as: Landete P, et al. Síndrome de Apert y apnea de sueño. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49:364–5.