Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is a complication of advanced cancer, and has an estimated incidence of 1/1000 people per year.1 It is predicted that the prevalence of MPE will increase in the next few years due to the greater survival of patients with active tumors.

Cure rates in MPE are low, and in most cases the effusion is recurrent. Onset occurs with increasing dyspnea, cough, chest pain, and loss of quality of life, so different therapeutic techniques with palliative intent are used. Pleurodesis was the technique of choice for many years, but tunneled pleural drainage (TPD) is now gaining more prominence in clinical practice.2–4 In the follow-up of tunneled catheters, formation of fibrinous septa in the interior of the effusion can be observed in up to 14% of patients.5 This is the result of procoagulant activity and the decline of fibrinolytic activity of MPEs, which contributes to the deposit of fibrin in the pleural space, creating septa that make it difficult to perform pleural effusion drainage in the patient's home. The benefit of urokinase instillation in these cases has been reported by several authors,6,7 some of whom opt for high doses over prolonged periods.8 Hsu et al., in 2006, recommended repeated instillations of 100000IU urokinase daily for at least 3 days (up to a maximum of 9 days and 900000IU urokinase)9; in contrast, other authors such as Mishra et al., in 2018,10 used 3 doses of 100000IU urokinase instilled at 12-h intervals for a total dose of 300000IU, with monitoring 24h after the last dose, but reported no significant benefit in the urokinase group.

We present a clinical case treated according to our hospital protocol for septated MPEs that are not effectively drained.

This was a 61-year-old man, referred to the respiratory medicine outpatient department for generalized constitutional symptoms, dyspnea on minimal effort and recurrent pleural effusion. He underwent 2 thoracenteses in the emergency department, for diagnosis and evacuation; a total of 2700ml lymphocytic exudate was extracted, and cytology was negative for malignancy. In the respiratory medicine clinic, we performed a chest ultrasound which revealed pleural thickening. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was requested, showing grade III/IV right pleural effusion causing right lower lobe atelectasis that contained a 2cm nodular image and multiple foci of tumor-like pleural nodular thickening. The abdomen was significant for a pathological retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy measuring 2cm in its greatest diameter. A right pleural ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed and thoracentesis for drainage was repeated (the third within a week, extracting 2000ml). The pathology study reported renal cell carcinoma metastasis as a primary neoplasm.

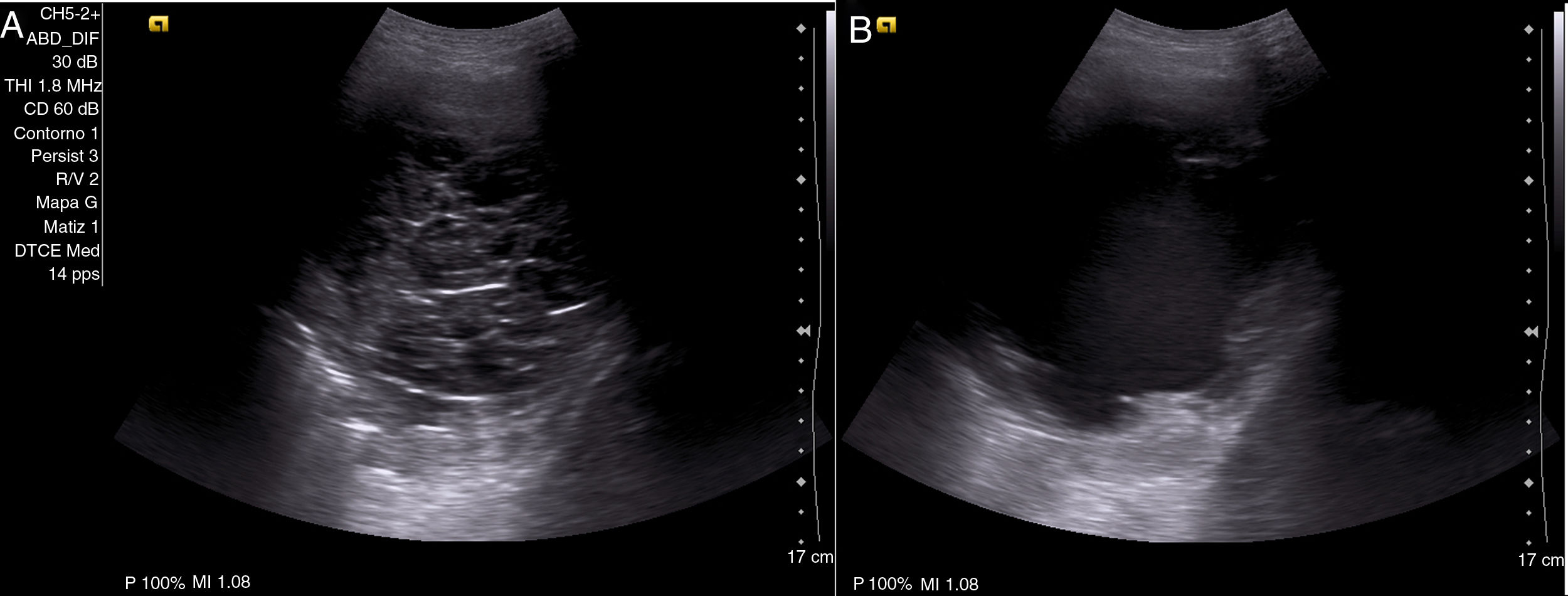

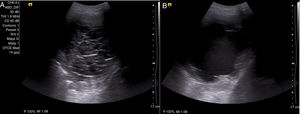

A diagnosis of MPE due to stage IV kidney cancer was made, and in view of the persisting pleural effusion, we decided, after explaining the different therapeutic alternatives to the patient, to place a TPD catheter (IPC™ Rocket Medical©, Watford, United Kingdom), and both the patient and his family members were instructed how to perform drainage at home. About 30 days after TPD placement, the patient attended the clinic with dyspnea on minimal effort (visual analog scale [VAS]: 8/10, modified Medical Research Council dyspnea grade: III), with ineffective TPD draining. Chest X-ray revealed grade II/IV right pleural effusion, unchanged from previous studies, with the catheter placed correctly in the right hemithorax. A chest ultrasound showed grade II/IV effusion containing multiple septa and detritus (Fig. 1A). An intrapleural instillation of 100000IU urokinase was administered and left to act for 2h, after which chest ultrasound was repeated, according to our protocol; this showed total lysis of the septa and persistent pleural effusion with detritus (Fig. 1B). This effusion was drained, obtaining 750ml of serosanguineous fluid; no associated complications were reported, and the patient showed significant symptomatic relief.

Patient, 61 years of age, with malignant pleural effusion due to stage IV kidney cancer, presenting with non-draining tunneled catheter. Chest ultrasound showing abundant septa preventing drainage of pleural fluid (A). A single dose of 100000IU urokinase was instilled and left to act for 2h; the thoracic ultrasound was then repeated, revealing pleural effusion containing detritus and lysis of the septa (B). The effusion was than drained, obtaining 750ml of serosanguineous pleural fluid and subsequent symptomatic improvement.

In October 2017, we implemented our protocol for home-managed MPE that does not drain after connecting the TPD tube to the vacuum bottle. This protocol consists of an initial chest X-ray and pleural ultrasound and, if intrapleural septa are observed on the latter, a single dose of 100000IU urokinase is instilled and the patient is reevaluated at 2h by repeating the ultrasound to visualize the effect of the urokinase (lysis of the septa), and then immediately performing drainage through the tunneled catheter.11 A third pleural ultrasound is performed to confirm the reduction of the pleural effusion and the absence of immediate complications. The procedure takes less than 10min from the time of the initial ultrasound to the intrapleural administration of the fibrinolytic agent, and another 10min between subsequently visualizing septal lysis and draining the effusion. On discharge, the patient is given a contact telephone number to report any possible complications (effusion becoming hemorrhagic, principally, or onset of dyspnea or chest pain).

Fifteen patients have been included in this protocol to date, 53.8% men, with an average age (standard deviation, SD) of 68.5 (13.9) years, and an average (SD) of 584 (199) cc drained after the procedure. Clear symptomatic relief (reduction of >2 points on VAS) was obtained in 73.3% of cases, and no complications have been observed so far.

The dose of urokinase required in MPE is not clearly established, and in our experience a high success rate is achieved in septal lysis with a single dose. As previously mentioned, recent studies published in the literature support the instillation of fibrinolytic agents over several consecutive days with subsequent assessments; however, this approach requires several visits and increases costs, and the patient is obliged to spend more time in the hospital.12 Since most patients with advanced disease are receiving palliative care, one of the main objectives should be to prioritize the well-being of the patient and reduce the number of visits to the hospital. With this systematic intervention, effective septal fibrinolysis is achieved in a single visit, without affecting the main objective of the procedure, which is to optimize pulmonary reexpansion, reduce pleural effusion, and improve the patient's dyspnea.

Please cite this article as: Herrero Huertas J, López González FJ, García Alfonso L, Enríquez Rodríguez AI. Fibrinólisis ambulatoria en el manejo del derrame maligno multiseptado. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019;55:594–596.