We report the case of a 36-year-old man with a history of mild mental retardation and esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula operated at birth, who was admitted to the intensive care unit with symptoms of intestinal obstruction, probably caused by medications, and generalized respiratory failure caused by bronchoaspiration, requiring orotracheal intubation (OTI).

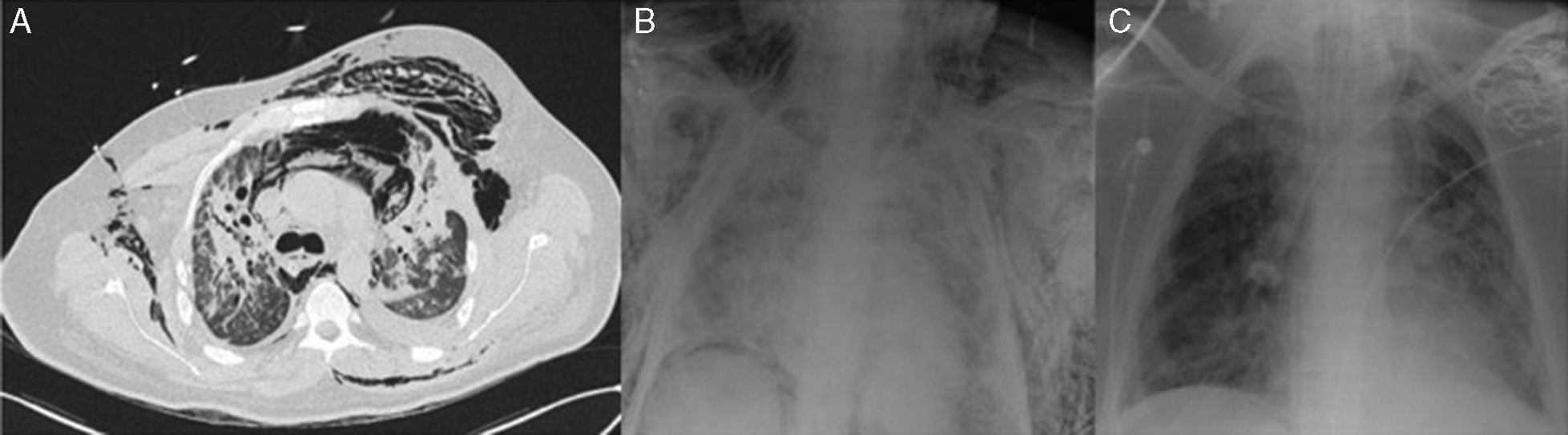

Twelve days after admission, percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy was performed. Forty-eight hours after the procedure, the patient presented significant subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum (Fig. 1A), so the tracheal cannula was removed and the patient was reintubated. The patient's general condition worsened progressively, with respiratory acidosis, hypercapnia >100mmHg, PaO2/FiO2 <200mmHg, severe respiratory difficulties, and incipient arterial hypertension. The chest X-ray showed bilateral alveolar-interstitial infiltrates and bronchoscopy revealed a 2cm rupture in the distal third of the trachea. The lesion was situated at the end of the orotracheal tube, so the tube was advanced with the fiberoptic bronchoscope until the distal end was in the right main bronchus (Fig. 1B). Despite this maneuver, the patient's poor respiratory status, consistent with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) persisted, so we decided to administer support therapy with venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO). After the patient's hemodynamic and respiratory situation stabilized, a self-expanding fully-coated nitinol tracheal stent was placed and the orotracheal tube was relocated to the site of the stent, re-establishing bipulmonary ventilation (Fig. 1C). After 13 days of support, ECMO was withdrawn and bronchoscopy-guided tracheostomy was performed. The patient remained stable and was discharged, almost 3 months after admission, after withdrawal of the cannula and removal of the stent by bronchoscopy.

Tracheobronchial lesions caused by tracheostomy are rare, occurring at a rate of around 0.2%–0.7%.1 In our case, the procedure may have been complicated by the patient's history of repaired distal tracheoesophageal fistula and the resulting distortion of the tracheal pars membranosa in this region, increasing the chance of injury. Self-expanding prostheses are a useful therapeutic option, particularly in patients with a high surgical risk, or in those in whom conservative treatment is ineffective.2

ARDS is associated with a mortality of 45%–55%.3 A protective pulmonary ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes and prone positioning of the patient are the only therapeutic measures shown to improve survival.4 In this context, ECMO-VV support provides good oxygenation and ventilation, therefore minimizing ventilatory support and barotrauma associated with mechanical ventilation.5

Our patient's situation was complicated by lesions caused by aspiration, and we found it impossible to keep him properly ventilated, so lung function support with VV-ECMO was required before the tracheal stent could be placed. This case demonstrates the benefit of ECMO in the management of patients with ARDS, and its utility as a bridge to the definitive treatment of tracheal rupture.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Hernández MT, Rodríguez-Pérez M, Varela-Simó G. Síndrome de distrés respiratorio agudo secundario a rotura traqueal postraqueostomía tratado con membrana de oxigenación extracorpórea venovenosa y prótesis endotraqueal. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:337–338.