Human pulmonary dirofilariasis is an uncommon parasitosis caused by Dirofilaria immitis. The usual hosts and reservoirs are domestic and wild carnivores, while humans are inadvertent hosts through the vector by mosquito bites. Pulmonary infection is extremely rare, often asymptomatic and usually discovered on routine chest radiograph as a solitary lesion, commonly mislabeled as malignant tumor.1

A 45-year-old Caucasian female was referred to the family doctor complaining of influenza-like symptoms and chest pain. She was a smoker (1 pack-day over the last 15 years), but had no contact with dogs or other pets. She denied any travel outside Greece. Chest X-ray revealed a small peripheral solitary pulmonary nodule in the right upper lobe. Clinical examination was unremarkable. White blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were normal. Tuberculin skin test was negative, as was sputum testing for common bacteria, and so empirical antibiotic therapy was initiated. One month later, symptoms were resolved but a new X-ray showed no radiological change, so lung cancer was suspected.

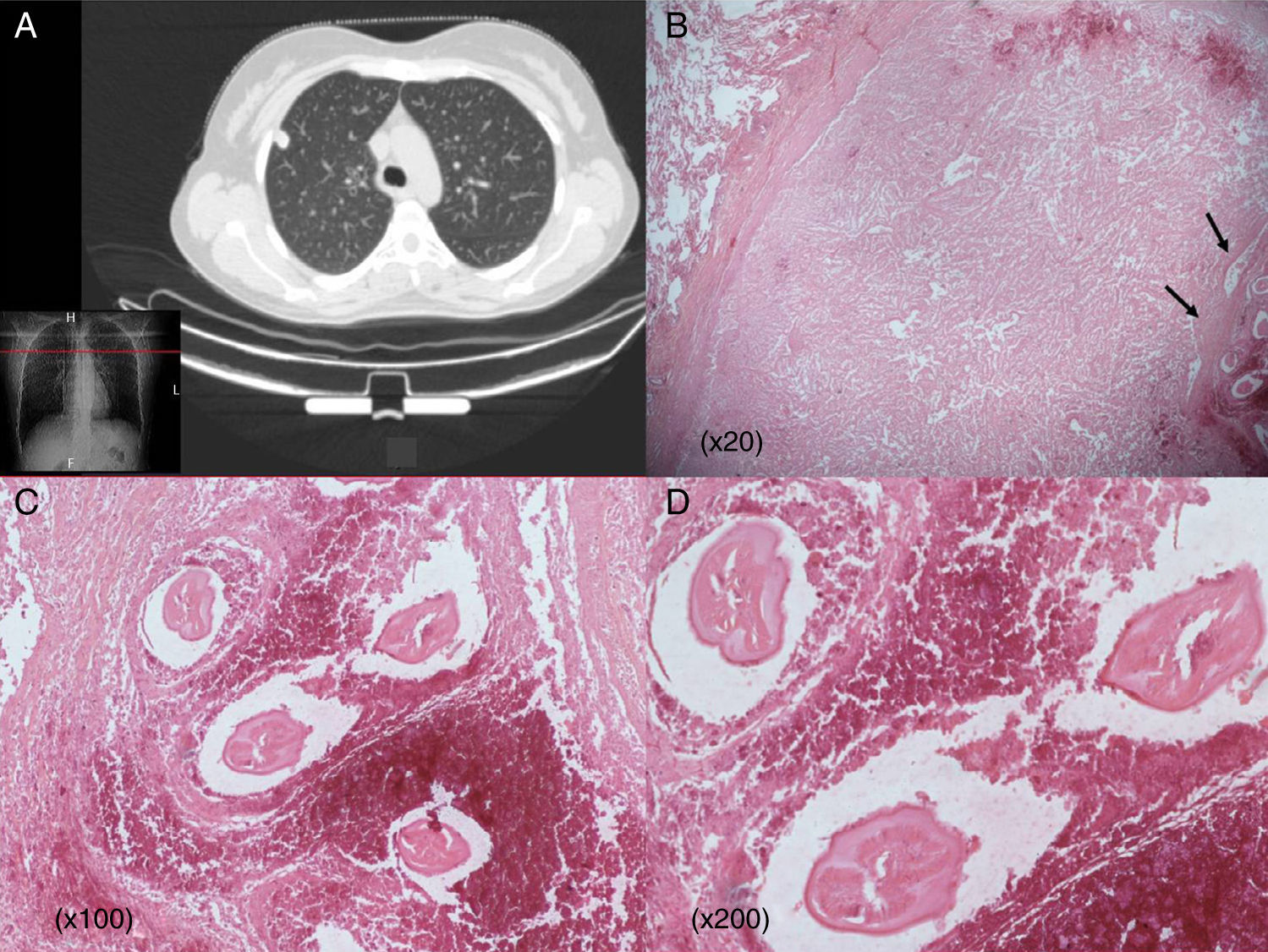

Computed tomography of the chest showed a well-defined 1.5cm non-calcified nodule located peripherally on the right upper lobe abutting the parietal pleura with no lymphadenopathy. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was normal. Microbiological and cytological analyses of bronchoalveolar lavage were negative. Immunological tests and screening for vasculitis were also negative.

Surgical resection was performed to rule out the tumor hypothesis. A 1.5cm soft grayish yellow nodule was found on the upper lobe, not directly in contact with the pleura. A wedge resection of the nodule was performed. Frozen sections showed a benign lesion characterized by necrosis. Final microscopic examination documented a well-circumscribed necrotic nodule containing fragments of a non-viable parasite that had features of D. immitis, including a smooth surface and internal longitudinal ridges. The nodule was surrounded by a fibrous wall with inflammatory reaction composed of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and did not require further medical treatment.

In Europe, human pulmonary dirofilariasis caused by the canine heartworm D. immitis is rare. Extra-pulmonary infection has also been reported.2 Humans become infected through mosquito bites but infection is not transmitted either from person-to-mosquito-to-person or from person-to-person, because humans are the “dead-end” hosts.3

Differential diagnosis of a pulmonary coin lesion between malignant tumor and benign lesion is always a diagnostic challenge. Existing serologic assays lack sensitivity and specificity, and should be used to supplement other data.5 Histologic identification of the nematode through surgical biopsy is still considered the best diagnostic approach, despite the high iatrogenic risk. Since humans are the “dead-end hosts”, definitive therapy is surgical resection, and further medical treatment is not required.3

Dirofilaria is endemic in the Mediterranean region, but the distribution of the disease is changing due to increasing environmental temperatures.4 However, knowledge regarding incidence is limited by the lack of registry and data are derived only from isolated reported cases. In Europe, fewer than 40 cases of pulmonary dirofilariasis have been reported, 3 of which were in Greece (Fig. 1).3

(A) Chest CT scan showing an apparently malignant solitary nodule in the right upper lobe abutting the pleura. (B) Well-defined necrotic pulmonary nodule invading normal lung parenchyma. Worms in necrotic tissue (arrows) (20×). (C and D) Typical dirofilariasis worms (D. immitis) embedded in necrotic material (C: hematoxylin and eosin staining 100×; D: hematoxylin and eosin staining 200×).

Please cite this article as: Sileli M, Tsagkaropoulos S, Madesis A. Dirofilariasis pulmonar: un escollo en el diagnóstico en la práctica clínica. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:338–339.