Smoking-attributable mortality (SAM) is a valuable indicator that can be used to characterize the course and health burden of the smoking epidemic. The aim of this paper was to estimate SAM in Spain in 2016 in the population aged 35 and over, using the best available evidence.

MethodsA smoking prevalence-dependent analysis based on the estimation of population-attributable fractions was performed. Smoking prevalence (never, former, and current smokers) was calculated from a combination of the Spanish Health Survey (2016) and the European Health Survey (2014); the relative risk of death among current and former smokers was taken from the follow-up of various cohorts; and mortality rates were obtained from National Center for Statistics data. SAM estimates are presented globally, and by sex, age groups, and major disease categories: cancer, cardiometabolic diseases and respiratory diseases.

ResultsIn 2016, 56,124 deaths were attributed to tobacco consumption, 84% in men (47,000), and 50% in the population aged over 74 (27,795). Overall, 50% of SAM was due to cancer (28,281), 65% of which was lung cancer. One in 4 attributable deaths (13,849) occurred before the age of 65.

ConclusionsOne in 7 deaths in Spain in 2016 were attributable to smoking. This estimation of SAM clearly highlights the great impact of smoking on mortality in Spain, mainly due to lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

La mortalidad atribuible (MA) al consumo de tabaco es un indicador valioso que permite caracterizar la evolución y el impacto en la salud poblacional de la epidemia tabáquica. El objetivo de este trabajo es estimar la MA al consumo de tabaco en España en 2016 en población ≥ 35 años utilizando la mejor evidencia disponible.

MétodosSe aplicó un método dependiente de las prevalencias de consumo de tabaco basado en el cálculo de fracciones atribuidas poblacionales. Las prevalencias de consumo (fumadores-exfumadores-nunca fumadores) proceden de la estimación combinada de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud-2016 y la Europea-2014; el exceso de riesgo de morir en fumadores y exfumadores del seguimiento de diferentes cohortes; y la mortalidad observada del Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Se presenta la estimación global de MA y en función del sexo, grupos de edad y grandes grupos de enfermedades (cáncer, cardiometabólicas y respiratorias), acompañadas de las fracciones atribuidas poblacionales.

ResultadosEn 2016 se atribuyeron 56.124 muertes al consumo de tabaco, el 84% sucedieron en hombres (47.000) y el 50% en mayores de 74 años (27.795). El 50% de la MA fue por tumores (28.281), de los cuales el 65% fueron de pulmón. Una de cada cuatro muertes (13.849) ocurrió antes de los 65 años.

ConclusionesUna de cada siete muertes que ocurrieron en España en 2016 se atribuyen al consumo de tabaco. Esta estimación permite objetivar el gran impacto que el consumo de tabaco tiene en la mortalidad, especialmente por cáncer de pulmón y enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica.

In 2014, the U.S. Department of Health published “The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress,”1 50 years after the first report of the agency on the health consequences of tobacco use was published on January 1, 1964.2 Since then, new diseases continue to be associated with smoking.

Although the prevalence of smoking has decreased in developed countries, it remains the preventable risk factor that causes most disease and death in the world.3 In this regard, one of the priorities set out in the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control4 is to monitor the trend in consumption and its impact on population health by estimating smoking-attributable mortality (SAM).

In Spain, different estimates are available to help determine the course of SAM both nationwide and in each autonomous community.5–11 However, changing patterns in the excess risk of death attributed to tobacco use, the prevalence of consumption, and associated causes of death mean that these estimates need to be updated.

The objective of this paper was to estimate SAM in Spain in 2016 using the best available evidence.

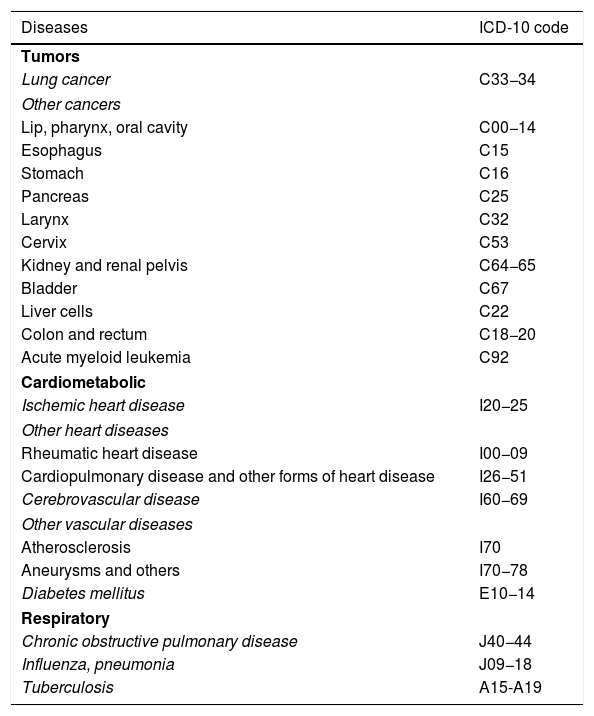

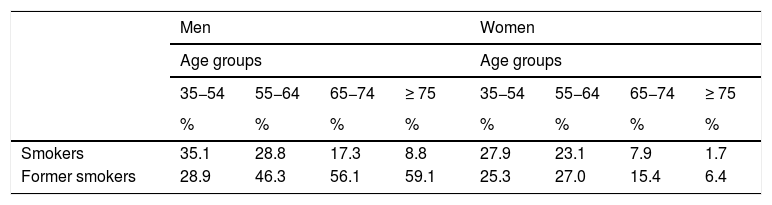

MethodsData sourcesMortality data were retrieved from the National Institute of Statistics, which provides information on cause of death according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). All deaths in Spain in 2016 that, according to the new update of the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC),12 were causally related to tobacco use were taken into consideration (see Table 1). It is worth highlighting at this point the inclusion of 4 diseases for which the evidence of causal relationship is recent: diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, liver cancer, and colorectal cancer. Prevalence of smoking, by sex and age groups (35−54; 55−64; 65−74 and ≥ 75 years), was derived from combined estimates of data from the National Health Survey conducted in 2016 and the European Health Survey for Spain of 2014 (Table 2). The data were combined taking into account the number of never smokers, smokers, and former smokers, and the populations included in each survey, calculating estimates, assigning weights to each observation to correct deviations in the selection of individuals with respect to their population distribution by age, sex, province, and household size. Relative risks were derived from the follow-up of 5 large cohorts: the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study, the American Cancer Society’s CPS-II Nutrition Cohort, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), the Nurses’ Health Study, and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study.12,13

Causes of mortality with established causal association with smoking, corresponding with International Classification of Diseases codes 10th edition (ICD-10).

| Diseases | ICD-10 code |

|---|---|

| Tumors | |

| Lung cancer | C33−34 |

| Other cancers | |

| Lip, pharynx, oral cavity | C00−14 |

| Esophagus | C15 |

| Stomach | C16 |

| Pancreas | C25 |

| Larynx | C32 |

| Cervix | C53 |

| Kidney and renal pelvis | C64−65 |

| Bladder | C67 |

| Liver cells | C22 |

| Colon and rectum | C18−20 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | C92 |

| Cardiometabolic | |

| Ischemic heart disease | I20−25 |

| Other heart diseases | |

| Rheumatic heart disease | I00−09 |

| Cardiopulmonary disease and other forms of heart disease | I26−51 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | I60−69 |

| Other vascular diseases | |

| Atherosclerosis | I70 |

| Aneurysms and others | I70−78 |

| Diabetes mellitus | E10−14 |

| Respiratory | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | J40−44 |

| Influenza, pneumonia | J09−18 |

| Tuberculosis | A15-A19 |

The causes included are those with established causal association with smoking according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.12

Prevalence of current and former smokers in the Spanish population ≥ 35 years, 2014-2016.

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | Age groups | |||||||

| 35−54 | 55−64 | 65−74 | ≥ 75 | 35−54 | 55−64 | 65−74 | ≥ 75 | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Smokers | 35.1 | 28.8 | 17.3 | 8.8 | 27.9 | 23.1 | 7.9 | 1.7 |

| Former smokers | 28.9 | 46.3 | 56.1 | 59.1 | 25.3 | 27.0 | 15.4 | 6.4 |

Prevalence is derived from the estimation of the combined data from the 2016 National Health Survey and the 2014 European Health Survey for Spain.

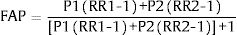

A prevalence-dependent method based on the calculation of population attributed fractions (PAF) was used to estimate SAM. This method estimates SAM as the product of observed mortality and PAF:

P1 denotes the prevalence of current smokers and P2 the prevalence of former smokers; RR1 and RR2 correspond to the risk that smokers and former smokers have of dying from smoking-related diseases, taking the group of never smokers as reference.

The overall SAM was estimated, based on sex and age groups (35−54, 55−64, 65−74 and ≥75 years) and 3 disease groups: cancer, cardiometabolic diseases and respiratory diseases.

ResultsIn Spain, 56,124 deaths were attributed to smoking in the population over 34 years of age, a figure which represents 13.7% of total mortality in 2016.

Detailed estimates are shown in Table 3. In total, 84% of SAM occurred in men (47,000), and 50% in the population over 74 years of age (27,795). Half (50%) of SAM was due to tumors (28,281), 65% of which were lung cancer. Half (51%) of the deaths were associated with 2 specific causes: lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (24,244 deaths in men and 4433 in women). In both men and women, lung cancer was the disease to which the highest mortality was attributed, irrespective of age group (15,214 deaths in men and 3020 deaths in women).

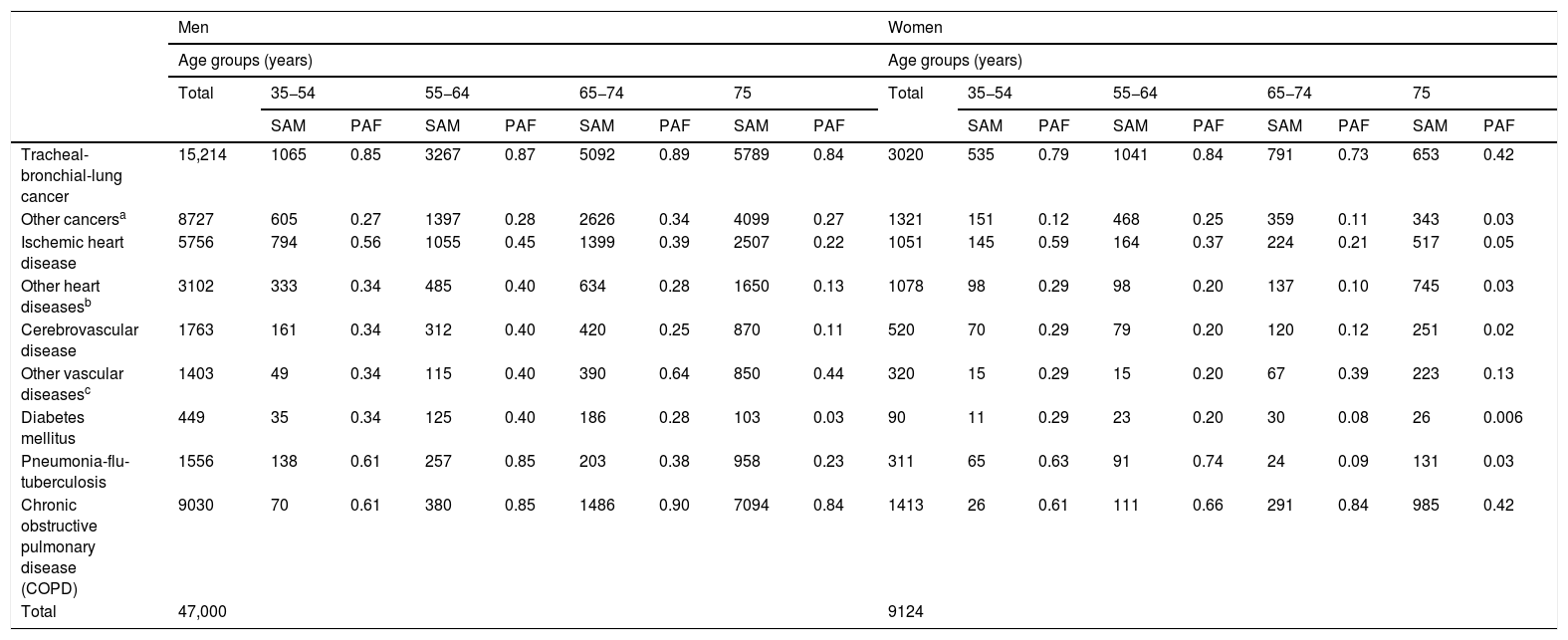

Number of deaths attributable to smoking (SAM) and population attributed fractions (PAF) according to sex and age group. Spain, 2016.

| Men | Women | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | Age groups (years) | |||||||||||||||||

| Total | 35−54 | 55−64 | 65−74 | 75 | Total | 35−54 | 55−64 | 65−74 | 75 | |||||||||

| SAM | PAF | SAM | PAF | SAM | PAF | SAM | PAF | SAM | PAF | SAM | PAF | SAM | PAF | SAM | PAF | |||

| Tracheal-bronchial-lung cancer | 15,214 | 1065 | 0.85 | 3267 | 0.87 | 5092 | 0.89 | 5789 | 0.84 | 3020 | 535 | 0.79 | 1041 | 0.84 | 791 | 0.73 | 653 | 0.42 |

| Other cancersa | 8727 | 605 | 0.27 | 1397 | 0.28 | 2626 | 0.34 | 4099 | 0.27 | 1321 | 151 | 0.12 | 468 | 0.25 | 359 | 0.11 | 343 | 0.03 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 5756 | 794 | 0.56 | 1055 | 0.45 | 1399 | 0.39 | 2507 | 0.22 | 1051 | 145 | 0.59 | 164 | 0.37 | 224 | 0.21 | 517 | 0.05 |

| Other heart diseasesb | 3102 | 333 | 0.34 | 485 | 0.40 | 634 | 0.28 | 1650 | 0.13 | 1078 | 98 | 0.29 | 98 | 0.20 | 137 | 0.10 | 745 | 0.03 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1763 | 161 | 0.34 | 312 | 0.40 | 420 | 0.25 | 870 | 0.11 | 520 | 70 | 0.29 | 79 | 0.20 | 120 | 0.12 | 251 | 0.02 |

| Other vascular diseasesc | 1403 | 49 | 0.34 | 115 | 0.40 | 390 | 0.64 | 850 | 0.44 | 320 | 15 | 0.29 | 15 | 0.20 | 67 | 0.39 | 223 | 0.13 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 449 | 35 | 0.34 | 125 | 0.40 | 186 | 0.28 | 103 | 0.03 | 90 | 11 | 0.29 | 23 | 0.20 | 30 | 0.08 | 26 | 0.006 |

| Pneumonia-flu-tuberculosis | 1556 | 138 | 0.61 | 257 | 0.85 | 203 | 0.38 | 958 | 0.23 | 311 | 65 | 0.63 | 91 | 0.74 | 24 | 0.09 | 131 | 0.03 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 9030 | 70 | 0.61 | 380 | 0.85 | 1486 | 0.90 | 7094 | 0.84 | 1413 | 26 | 0.61 | 111 | 0.66 | 291 | 0.84 | 985 | 0.42 |

| Total | 47,000 | 9124 | ||||||||||||||||

One in 4 deaths (13,849) were premature, i.e., before the age of 65. The proportion of premature deaths in men was 22.6% and 35.1% in women.

SAM increased with age in both men and women. The highest SAM observed in the group aged ≥ 65 years is explained by the increase in observed mortality, since the PAF is the lowest in this group, except in men for COPD. The estimated PAFs for lung cancer and COPD in both men and women are remarkable for any age. Thus, 85% of lung cancer mortality in men and 80% in women aged 35−54 years is associated with smoking; for COPD between the ages of 55−64 years, these percentages are 85% and 66% (Table 3).

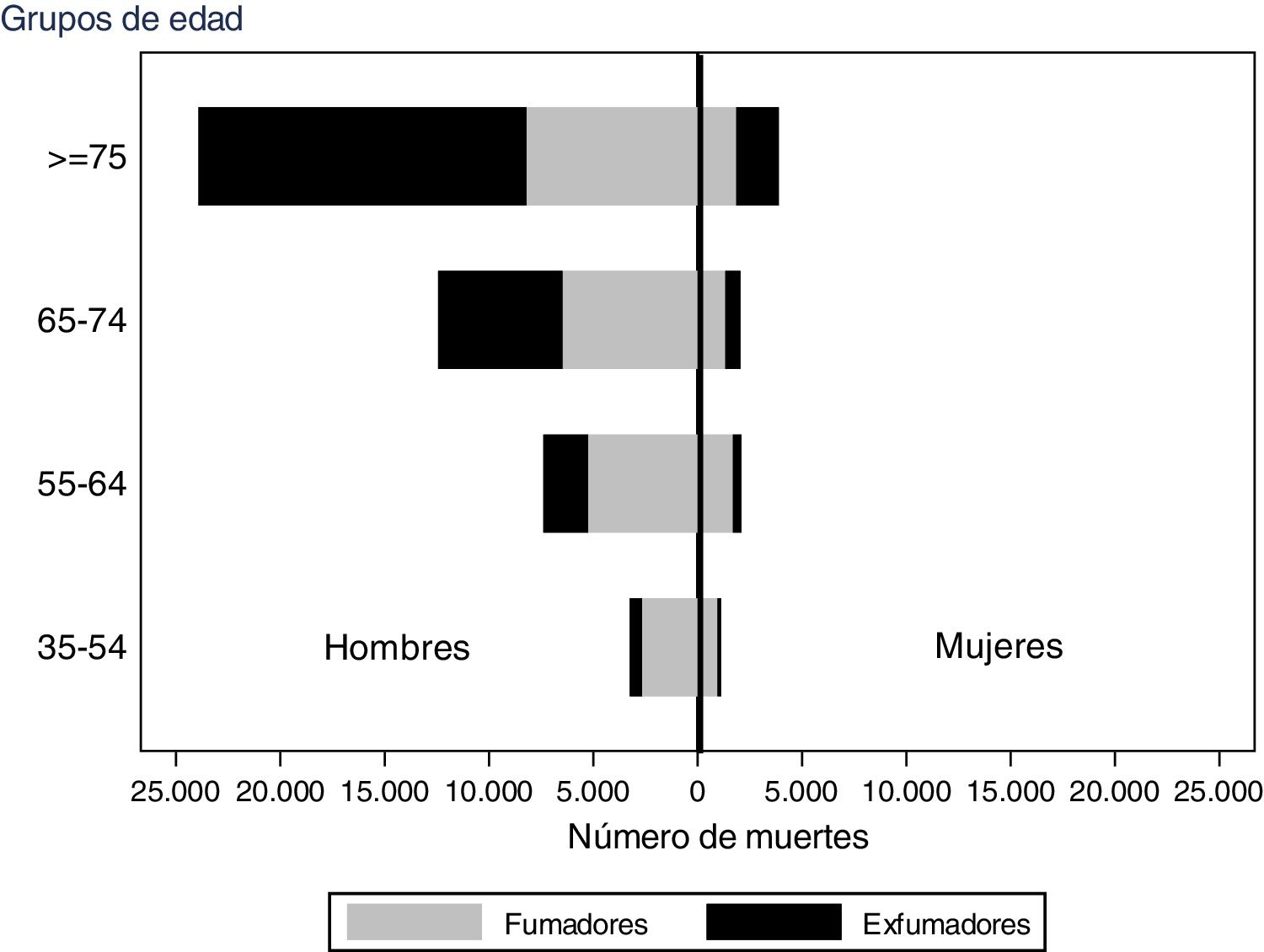

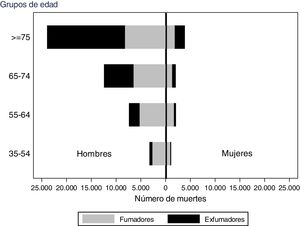

Fig. 1 shows SAM by sex and age groups according to smoking habit (smokers, former smokers). Between the ages of 35 and 74, the highest mortality burden in both sexes is observed in the smoking population, while from the age of 75, the highest number of deaths is observed in former smokers, especially in men.

DiscussionThis study updates SAM among the Spanish population in 2016 using a methodology based on the calculation of the estimated attributed fraction from the prevalences of smokers and former smokers categorized in 4 age groups, while incorporating new diseases for which causal evidence has been shown to be consistent. The mortality burden due to this risk factor, accounting for 1 in 7 deaths, remains very high.

In Spain, the latest estimates using comparable methodology suggest that smoking caused 259,348 deaths in the 5-year period 2010–2014, or in other words, an average of 51,870 deaths a year. Another observation was that age-adjusted SAM in the current century shows a downward trend in men but an upward trend in women.11

The methodological update proposed by the CDC introduces a more detailed categorization of age groups, increasing from 2 groups to 4, in order to better capture the variability of RR and prevalence of smoking associated with age. It also incorporates 4 new diseases: diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, liver cancer, and colorectal cancer, for which evidence is now sufficient to infer a causal association. In order to assess the impact of methodological changes on the estimation of SAM, a sensitivity analysis was conducted comparing the estimates obtained with both methods. Thus, when the previous methodology also proposed by CDC14 was used, 50,222 deaths were estimated, 5900 less than with the current methodology. This difference is mainly due to the different distribution of RR in the 4 age groups. The reduction mainly applies to cardiovascular disease and cancer. This estimate, using the previous methodology, also allows SAM in 2016 to be compared with the latest estimates available for the whole of Spain, from 2006. Overall, SAM fell by 2933 deaths when the 2006 estimates were compared with the 2016 estimates. This decrease is seen only in men. In 2006, smoking was estimated to have caused 53,155 deaths in Spain with a relative male/female difference of 7.9 (41,193 deaths in absolute terms); in 2016, the SAM was estimated at 50,222 with a relative difference of 7.0 (36,178 deaths in absolute terms). A decreasing difference between sexes in SAM has been observed in Spain since the beginning of the 21 st century,10 linked to the decrease in the difference between the prevalence of smoking between the sexes resulting from the decrease in the prevalence of smoking among men.11

SAM estimates should be viewed with caution, as both the estimation method and the data used for the calculation have certain limitations. These include, in particular, the overlap in time between observed mortality and prevalence of smoking, i.e. the time lag between exposure and effect is not taken into account. In this regard, bearing in mind that the prevalence of smoking has decreased in Spain, the estimates obtained would underestimate SAM.12 It should also be taken into account that exposure, i.e. the prevalence of smoking, comes from self-declared data, so some degree of underestimation is likely.15 Nor do the estimates take into account the intensity or the period of time during which the individual smoked, despite duration of exposure being particularly closely associated with mortality.16 Furthermore, it should be noted that RR estimates, understood as the excess risk of death among smokers and former smokers compared with never smokers, are derived from studies performed in the United States, where the course of the smoking epidemic is different from that observed in Spain. These RRs have not been adjusted for potential confounding factors such as environmental pollution, level of studies, or other lifestyle factors, resulting in the use of higher RRs in the absence of adjustment (positive confounding). However, the magnitude of this deviation is small,17,18 and the relative reduction in SAM is estimated at 1%.19 While taking into account these methodological limitations, it should be noted that RRs from these studies are the best evidence available for assessing the excess risk of death associated with smoking.

ConclusionsThe estimation of SAM is a useful tool for the planning, management and evaluation of health policies aimed at both the prevention of smoking and the promotion of smoking cessation. The heavy burden that smoking continues to impose on our society means that these policies must be intensified, especially strategies aimed at the prevention of starting the habit. From a healthcare point of view, the estimation of SAM makes it possible to target the impact of smoking and to produce population-oriented health messages. Thus, the knowledge that 90% of lung cancer deaths in men aged 65–74 years and 84% of COPD deaths in women aged 55–64 years would have been avoided if they had not smoked is an irrefutable message that should provide food for thought to both health professionals and society as a whole.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Ríos M., Schiaffino A., Montes A., Fernández E., López M.J., Martínez-Sánchez J.M., et al. Mortalidad atribuible al consumo de tabaco en España 2016. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:559–563.