Journal Information

Vol. 61. Issue 4.

Pages 229-231 (April 2025)

Share

Download PDF

More article options

Vol. 61. Issue 4.

Pages 229-231 (April 2025)

Scientific Letter

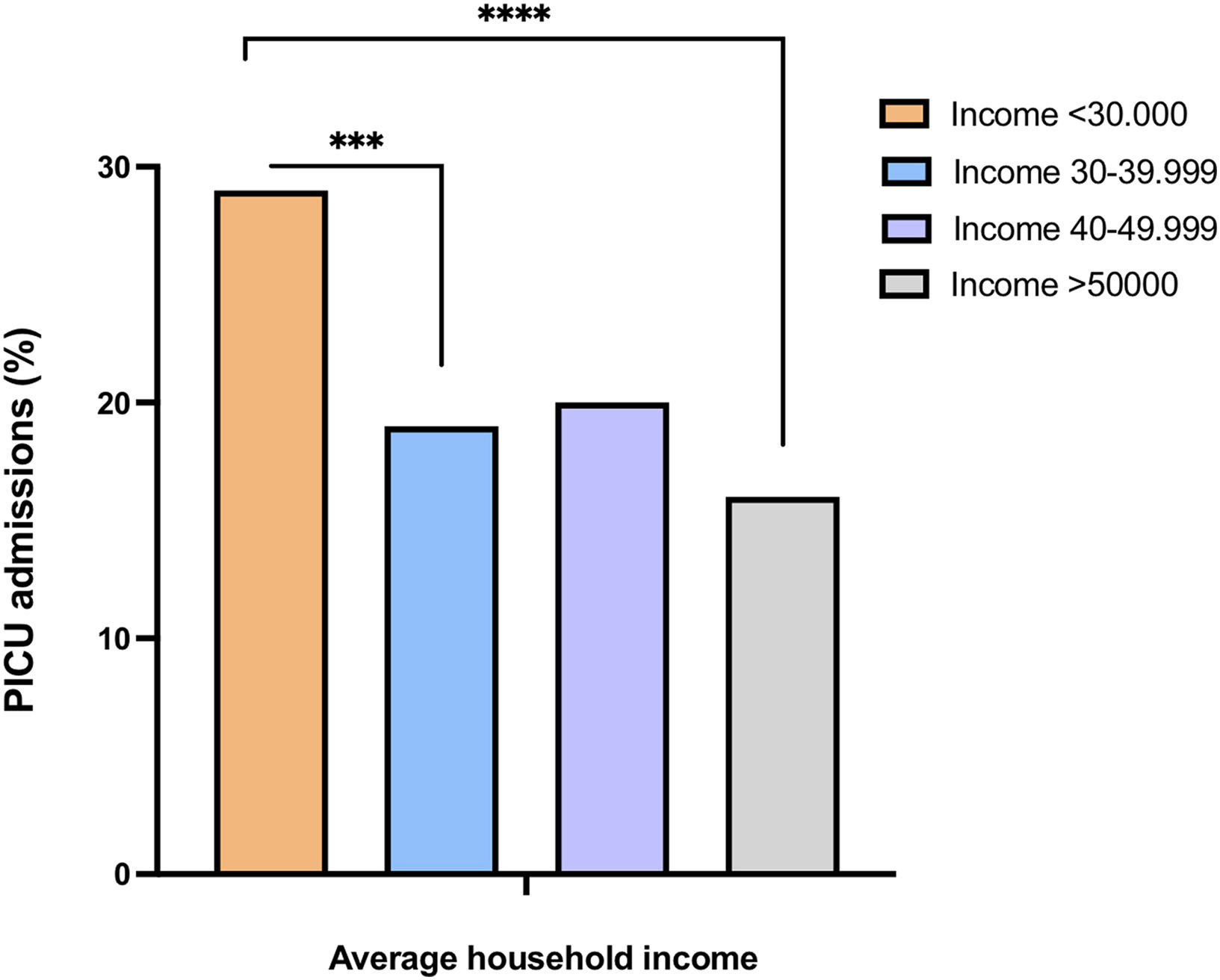

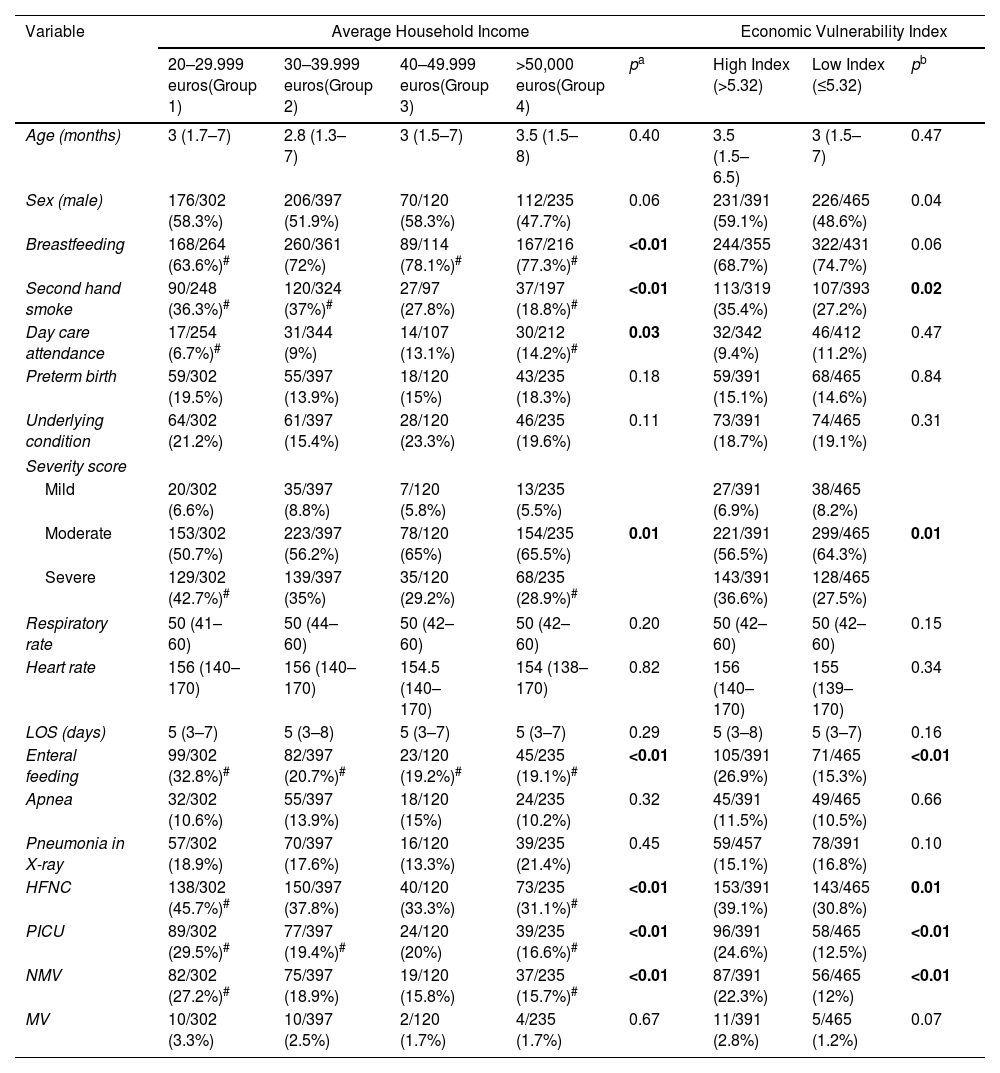

The Importance of ZIP Code-related Average Household Income on the Severity of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Infants

Visits

465

This item has received

Article information

These are the options to access the full texts of the publication Archivos de Bronconeumología