We report the case of a 58-year-old man with HIV infection, COPD and history of intravenous drug use, who was admitted to the hospital with bilateral lower extremity weakness and multiple falls over the past 3 months. He denied myalgias, paresthesias, fever or chills. The patient was compliant with his highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) that included lopinavir (500mg twice daily), ritonavir (125mg twice daily), efavirenz (600mg once daily) and lamivudine (300mg once daily). He was also taking inhaled fluticasone propionate-salmeterol (250/50 mcg, 2 puffs twice a day) and inhaled ipratropium for COPD.

Examination revealed a significant reduction in strength of bilateral hip flexion (2/5) and shoulder abduction (4/5) with relatively preserved distal motor strength. Deep tendon reflexes and sensory exam were normal. Significant laboratory abnormalities included a slightly elevated serum aldolase 10.8U/L (N: 1.5–7U/L) but CPK was normal (33U/L). HIV viral load was undetectable and CD4 count was 400. Thyroid function tests were normal. At this point, our differential diagnoses included inflammatory myopathies such as polymyositis and inclusion body myositis, HIV myopathy and anti-retroviral induced myopathy. We also considered the possibility of myotonic dystrophy, muscular dystrophy, and myasthenia gravis.

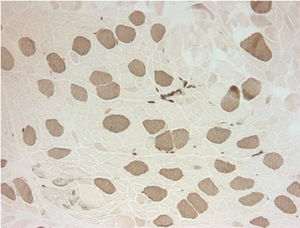

Electromyography results were indeterminate; therefore, a biopsy was obtained from the left quadriceps muscle. It showed atrophic changes affecting type 2 fibers (Fig. 1). The biopsy showed no evidence of an inflammatory myopathy and there were no mitochondrial changes as those described in association with anti-retroviral drugs. The histopathologic findings seen in our patient have been reported to be potentially consistent with myopathy secondary to disuse or glucocorticoids.2,3 Disuse atrophy was unlikely in our patient as he had been active until 3 months ago when the muscle weakness started. At this point, the possibility of glucocorticoid-induced myopathy was strongly considered. The only steroid that our patient had been exposed to was the inhaled steroid (fluticasone propionate). It was stopped and the patient showed marked improvement over the course of 4–6 weeks.

Looking back at our case, we realized that in the past our patient had been treated with Zidovudine/Lamivudine and Nelfinavir mesylate. 9 months earlier following HIV resistance testing, his HAART had been switched to Lopinavir/Ritonavir, Efavirenz and Lamivudine. Also, 5 months prior to presentation the patient had been switched from beclomethasone inhaler to fluticasone propionate-salmeterol. Above timeline shows that there was a 2-month overlapping period where both fluticasone and ritonavir were co-administered prior to the onset of symptoms. Considering this information and prior case reports, we suspected that ritonavir likely played a role in precipitating fluticasone propionate induced myopathy. After 2 months, our patient was started on inhaled beclomethasone in place of fluticasone propionate. Ritonavir was continued along with rest of the HAART. There has been no recurrence of symptoms.

Fluticasone propionate is a commonly prescribed inhaled glucocorticoid for the treatment of conditions such as asthma and COPD. Inhaled fluticasone propionate can be absorbed from the lungs and exert a dose-dependent suppression of cortisol.4 However, it has extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver.5 Most of the fluticasone propionate in the bloodstream is broken down into inactive 17-carboxylic acid derivatives by cytochrome P-450 3A4 (CYP3A4). Therefore, systemic toxicity from fluticasone propionate, in the absence of significant drug interactions is exceedingly rare. In our review of the literature, we found only one report (two cases) of fluticasone propionate induced myopathy and that too in the pediatric population.6 Fluticasone propionate's pharmacokinetics can dramatically change when inhibitors of CYP3A4 are co-administered. Ritonavir, a protease inhibitor used as a component of HAART is a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor.7 This CYP3A4 inhibition is not only responsible for the therapeutic effects of ritonavir but also leads to drug interactions and adverse effects. There have been around 40 case reports of iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome secondary to potentiation of fluticasone propionate's effects because of co-administered ritonavir.8 Fluticasone propionate induced osteoporosis has also been reported in the setting of ritonavir co-administration.9 In fact, ritonavir and fluticasone propionate co-administration increases fluticasone propionate's area under the curve and maximum concentration by 350-fold and 25-fold respectively.10 Similar interactions between other inhaled glucocorticoids and CYP3A4 inhibitors are much less likely because fluticasone propionate causes the most significant cortisol suppression.11 Also, compared to other inhaled glucocorticoids, fluticasone propionate has higher receptor binding affinity, is highly lipophilic and has a larger volume of distribution.9

Unfortunately, HIV seropositive men are more likely to have bronchial hyperresponsiveness and suffer from effects of smoking.12 Therefore, a significant number of these patients will likely end up needing inhaled glucocorticoids while being on protease inhibitors such as ritonavir. Clinicians can reduce the risk of these patients developing complications such as Cushing's, osteoporosis and myopathy, by avoiding inhaled fluticasone propionate. Beclomethasone dipropionate, budesonide, flunisolide etc. are much safer alternatives. On the hand, if HIV resistance testing allows, patients can be switched from a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor therapy to raltegravir based HAART.13

While Cushing's syndrome and osteoporosis resulting from this drug interaction have previously been reported, we believe our case is the first report of isolated myopathy secondary to fluticasone propionate-ritonavir interaction. Our patient did not have other overt signs of glucocorticoid toxicity such as buffalo hump, abdominal striae, diabetes, hypertension etc., this led to a delay in recognition of this complication. Perhaps earlier recognition of this complication could have spared our patient an invasive procedure (muscle biopsy).

The authors are grateful to their colleagues at the Medical College of Wisconsin and the Cook County Hospital for their continued support. This case was previously presented at the annual American Thoracic Society (ATS) conference (2017).1