Fibrotic interstitial lung diseases (ILD) encompasses a heterogeneous spectrum of interstitial lung diseases of both known and unknown etiology, all characterized by radiologically confirmed fibrosis [1,2]. Non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) fibrotic ILDs are defined as progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) when specific radiological, clinical, and functional criteria are fulfilled [1,2]. Nintedanib, a multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to slow the rate of forced vital capacity (FVC) decline in patients with PPF [2,3] and currently remains the only antifibrotic agent recommended by the international guidelines [1]. Recent real-life studies have confirmed its effectiveness in attenuating the decline of lung function [4–6].

During treatment, patients may experience adverse events, predominantly gastrointestinal, which may necessitate temporary or permanent dose reduction or discontinuation, thereby resulting in reduced drug exposure [6,7]. Only limited evidence is available in the literature regarding the effectiveness of nintedanib in patients with pulmonary fibrosis in relation to dose intensity (DI).

Data from clinical trials and open-label extension studies showed no difference in the rate of FVC decline among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in relation to dose exposure [8,9]. A recent observational, retrospective study confirmed the absence of a significant difference in the decline of FVC and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) over 12 months in 54 patients with IPF treated with full versus reduced dose of nintedanib [10].

In a secondary analysis of the SENSCIS trial, the annual rate of FVC decline was not affected by dose adjustments in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) [11].

More recently, a post hoc analysis of INBUILD trial demonstrated that, in patients with PPF, the rate of lung function decline was comparable irrespective of the dose adjustments implemented to manage adverse events [12].

To date, no real-world data are available on the impact of dosing on clinical and functional outcomes in patients with PPF treated with nintedanib.

The aim of our study is to evaluate the effectiveness of antifibrotic therapy in relation to dose intensity (DI).

This is a secondary analysis of an observational, retrospective, multicentre study conducted in Italy, which aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of nintedanib using clinical, radiological and functional progression criteria [6].

From April 2022 to August 2024, consecutive adult (i.e., ≥18 years old) PPF patients with mild to moderate functional impairment (defined as FVC>45%) who were treated with nintedanib were enrolled. Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected at baseline. Functional data were recorded at baseline and at 12 months before and after treatment initiation. Information on exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality was also documented.

Dose intensity was calculated as the ratio between the actual amount of drug administered during the study period and the expected amount if the full 150mg twice-daily regimen had been maintained throughout the 52-week treatment period or until permanent treatment discontinuation [8,9,12].

Differences in functional decline, exercise capacity, incidence of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and deaths during treatment versus the year preceding antifibrotic initiation were analyzed according to DI (i.e., <80% vs. ≥80%) [8].

The sample characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to assess the normality of distributions. Differences between dosage groups (80% threshold) were assessed with the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, and with the t-test or Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables. Differences between time points were evaluated using McNemar's test for categorical variables and the paired t-test or Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All analyses were performed using STATA version 17.

A total of 172 patients with PPF, 91 being males (52.9%), with a median (IQR) age of 71 years (65.5–77.0), were recruited. Etiological diagnoses were the following: 45 (26.1%) fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, 57 (33.1%) connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease; 46 (26.7%) idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (18 non-specific interstitial pneumonias, 6 alveolar macrophage pneumonias, 2 cryptogenic organizing pneumonias); 24 (13.9) other diagnosis.

During the study period, 99 (57.6%) patients maintained a DI≥80% whereas 73 (42.4%) patients had a DI<80% (Table 1). A permanent and temporary discontinuation of the drug was recorded in 15 (9%) and 16 (9%) patients, respectively. A permanent dose reduction was needed in 29 (16%) patients: increased transaminases serum levels was the most common cause (21 patients).

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients related to dose intensity.

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | Dose intensity<80% (N=72) | Dose intensity≥80% (N=99) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) Age | 70.9 (9.7) | 69.6 (10.2) | 0.40 |

| Male, n (%) | 29 (40.3) | 62 (62.6) | 0.004 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 71 (98.6) | 98 (99.0) | 1.00 |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Mean (SD) Height (cm) | 162.8 (9.6) | 165.7 (10.9) | 0.07 |

| Median (IQR) Weight (kg) | 70 (59–78) | 78 (67–85) | 0.0002 |

| Median (IQR) BMI | 25.9 (23.1–28.4) | 27.2 (25–30.8) | 0.01 |

| ECOG performance status (0–5) | |||

| 0 | 9 (12.5) | 14 (14.3) | 0.11 |

| 1 | 28 (38.9) | 54 (55.1) | |

| 2 | 22 (30.6) | 23 (23.5) | |

| 3 | 8 (11.1) | 4 (4.1) | |

| 4 | 3 (4.2) | 3 (3.1) | |

| 5 | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mean (SD) Barthel Index | 97.8 (5.2) | 98.2 (4.8) | 0.09 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |||

| Never smoker | 38 (52.8) | 33 (34.0) | 0.02 |

| Former or active smoker | 34 (47.2) | 64 (66.0) | |

| Coronary artery disease | 14 (19.4) | 16 (16.2) | 0.58 |

| Chronic neurological disease | 7 (9.7) | 7 (7.1) | 0.53 |

| Arterial hypertension | 38 (52.8) | 53 (53.5) | 0.92 |

| Emphysema | 9 (12.5) | 21 (21.2) | 0.14 |

| Diabetes | 11 (15.3) | 11 (11.1) | 0.42 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 6 (8.3) | 3 (3.0) | 0.13 |

| Liver insufficiency | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.0) | 1.00 |

| OSAS | 7 (9.7) | 11 (11.1) | 0.77 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 16 (22.2) | 14 (14.1) | 0.17 |

| GERD | 23 (31.9) | 16 (16.2) | 0.02 |

| Lung cancer | 3 (4.2) | 2 (2.0) | 0.65 |

BMI: body mass index; ECOG: Eastern cooperative group; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome; GERD: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Patients with a DI≥80% were more frequently male, former or current smokers, and had a higher BMI compared with those with a DI<80%. Preexisting gastroesophageal reflux disease was significantly more common among patients who required a dose reduction.

Overall, 135 (78.5%) patients completed one year of treatment. After 12 months, 87 (64.4%) no longer met the INBUILD progression criteria, irrespective of DI (Supplementary Table 1).

FVC data were available for 132 (97.8%) patients, and DLCO data for 116 (85.9%) among the 135 who completed one year of treatment.

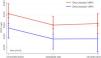

FVC (ml and % predicted) decline was significantly greater in the 12 months preceding treatment initiation compared with the 12 months following treatment, irrespective of DI. Median (IQR) FVC values were 2135 (1775–2800) ml vs. 1985 (1645–2610) ml (p<0.0001) and 1985 (1645–2610) vs. 2040 (1550–2620.5) (P: 0.29), for dose intensity<80% and 2480 (1855–3175) ml vs. 2350 (1730–2930) ml; p<0.0001; 2350 (1730–2930) vs. 2420 (1750–2900); p=0.86 for dose intensity≥80%, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Functional and clinical outcomes after 1 year of treatment with nintedanib related to dose intensity.

| Dose intensity<80% | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional outcomes | 12 months before Nintedanib start | Nintedanib start | p-Value |

| Median (IQR) dyspnea (mMRC) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) | <0.0001 |

| Median (IQR) FVC (ml) | 2135 (1775–2800) | 1985 (1645–2610) | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) FVC% | 79.9 (19.5) | 75.2 (22.6) | 0.0001 |

| Median (IQR) DLCO (ml/mmHg/min) | 9.7 (5.2–12.8) | 10.1 (7.2–12.7) | 0.91 |

| Median (IQR) DLCO% | 48 (40–60) | 44.5 (37–59) | 0.21 |

| Median (IQR) 6MWT (m) | 370 (300–420) | 380 (295–430) | 0.29 |

| Nintedanib start | 12 months after Nintedanib start | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) dyspnea (mMRC) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.10 |

| Median (IQR) FVC ml | 1985 (1645–2610) | 2040 (1550–2620.5) | 0.29 |

| Mean (SD) FVC % | 75.2 (22.6) | 72.5 (23.8) | 0.08 |

| Median (IQR) DLCO (ml/mmHg/min) | 10.1 (7.2–12.7) | 9.3 (4.2–11.4) | 0.01 |

| Median (IQR) DLCO % | 44.5 (37–59) | 42 (33.5–55) | 0.01 |

| Median (IQR) 6MWT | 380 (295–430) | 360 (300–420) | 0.26 |

| Dose intensity≥80% | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional outcomes | 12 months before Nintedanib start | Nintedanib start | p-Value |

| Median (IQR) dyspnea (mMRC) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) | <0.0001 |

| Median (IQR) FVC ml | 2480 (1855–3175) | 2350 (1730–2930) | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) FVC % | 82.7 (18.6) | 75.7 (18.9) | <0.0001 |

| Median (IQR) DLCO (ml/mmHg/min) | 10.5 (5.7–15.8) | 9.2 (6.3–12.6) | 0.001 |

| Median (IQR) DLCO % | 50 (41–62) | 45 (37–55) | <0.0001 |

| Median (IQR) 6MWT | 380 (300–420) | 350 (280–420) | 0.17 |

| Nintedanib start | 12 months after Nintedanib start | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) dyspnea (mMRC) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.10 |

| Median (IQR) FVC ml | 2350 (1730–2930) | 2420 (1750–2900) | 0.86 |

| Mean (SD) FVC % | 75.7 (18.9) | 74.5 (18.9) | 0.42 |

| Median (IQR) DLCO (ml/mmHg/min) | 9.2 (6.3–12.6) | 8.1 (4.7–11.8) | 0.002 |

| Median (IQR) DLCO % | 45 (37–55) | 42 (32–52) | 0.01 |

| Median (IQR) 6MWT | 350 (280–420) | 350 (280–420) | 0.68 |

| Clinical outcomes | Dose intensity<80% | Dose intensity≥80% | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute exacerbations n (%) | 11 (15.1) | 7 (7.1) | 0.08 |

| Hospitalizations n (%) | 10 (17.5) | 5 (8.1) | 0.12 |

| Deaths during study period n (%) | 5 (6.9) | 7 (7.1) | 1.00 |

FVC: forced vital capacity; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; 6mWT: 6-minute walking test; SpO2: peripheral oxygen saturation.

No differences were observed in the attenuation of FVC decline (ml) between patients with UIP and non-UIP computed tomography patterns in relation to DI (Supplementary Table 2).

Nintedanib did not significantly affect DLCO trajectories, irrespective of DI. Likewise, no statistical differences were detected in six-minute-walking distance across subgroups (Table 2).

Cough remained unchanged or improved after one year of treatment in 73% and 88% of patients with DI< and ≥80%, respectively.

The median (IQR) mMRC dyspnea score did not significantly change over the year of treatment in both subgroups (Table 2). Patients with a DI≥80% tended to have lower rates of acute exacerbation (7.1% vs. 15.1%, p=0.08) and hospitalizations (8.1% vs. 17.5%, p=0.12) than those with DI<80%, although these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2).

This is the first observational study designed to evaluate the impact of dosing on clinical and functional outcomes in patients with PPF treated with nintedanib. Our findings indicate that nintedanib slows disease progression and functional decline and positively affects clinical outcomes irrespective of DI.

This is a key finding, as in clinical practice a subset of patients may require temporary or permanent dose reduction or treatment interruption to mitigate toxicity and manage adverse events [6,12].

Our data show that female patients, those with lower BMI, and never-smokers are at higher risk of requiring dose reduction. Those observations are consistent with previous studies [11,12], which also reported more frequent dose reductions in females and patients with lower baseline BMI. As expected, patients with gastrointestinal comorbidities (e.g., GERD) more commonly required dose adjustment.

In our study, nintedanib mitigated symptoms worsening and FVC decline irrespective of dose reduction. These findings are consistent with previous studies in patients with IPF, which demonstrated attenuation of FVC decline regardless of dose reductions or adjustments during nintedanib treatment. In post hoc analyses of the INPULSIS and INPULSIS-ON trials, Maher et al. and Crestani et al. reported that treatment efficacy did not differ significantly between subgroups stratified by DI (<80% vs. ≥80% and <90% vs. ≥90%, respectively) [8,9].

More recently, a secondary analysis of the INBUILD trial reported that 48.2% of patients with PPF in the nintedanib group experienced at least one dose reduction and/or treatment interruption. The rate of FVC decline over 52 weeks was similar regardless of the dose adjustments or intensity used to manage adverse events [12]. In our study, nintedanib attenuated functional decline independently of DI and irrespective of computed tomography pattern (UIP vs. non-UIP).

Furthermore, we demonstrated for the first time that in patients with PPF treated with nintedanib, the incidence of acute exacerbations, hospitalizations, and death is not influenced by DI. These findings are consistent with those of a recent observational study based on a large cohort of patients with IPF, which reported no difference in the risk of hospitalizations and mortality between stable 150 and 100mg dosing, as well as among patients who switched doses of nintedanib during the observation period [13].

In conclusion, our study confirms that nintedanib may slow disease progression and lung function decline and first indicates that it is effective regardless of dose adjustments. DI does not appear to influence the incidence of acute exacerbations, hospitalizations, or mortality in patients with PPF, but this data should be confirmed in larger, prospective studies.

Further studies are warranted to confirm these findings and to directly compare lung function decline and clinical outcomes in patients with PPF receiving stable 100mg versus 150mg twice-daily dosing.

Authors’ contributionsJC contributed toward conception and design; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. FV contributed toward conception and design and acquisition of data; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. FL contributed toward conception and design and acquisition of data; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. PC contributed toward acquisition of data; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. SC contributed toward acquisition of data; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. MVP contributed toward analysis and interpretation of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. AM contributed toward acquisition of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. GF contributed toward acquisition of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. UZ contributed toward acquisition of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be submitted. TP contributed toward acquisition of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. AP contributed toward acquisition of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. LR contributed toward acquisition of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. EB contributed toward acquisition of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. GS contributed toward conception and design and analysis and interpretation of data; revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. MM contributed toward conception and design; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted.

Artificial intelligence involvementNone.

Funding of the researchThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflicts of interest that may be considered to influence directly or indirectly the content of the manuscript.