Estimates of COPD burden depend on data sources. According to 2021 global burden of diseases data, the total number of COPD patients (including all ages) is estimated to be 213 million, representing a prevalence of 2.7%.1 On the other hand, the results of a systematic review that included population-based studies conducted across 260 sites in 65 countries estimated a global prevalence of COPD in 2019 of 10.3% among people aged 30–79 years using the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD) definition and 7.6% using the lower limit of normal (LLN), which translates to 292.0 million people.2 Despite the current availability of broad and clear recommendations from different scientific societies and organizations on when to suspect and how to diagnose COPD, there is still a high underdiagnosis of the disease3 and data from around the world indicate that between 70% and 90% of people with COPD remain undiagnosed,4 especially in low- and middle-income countries. Subjects with undiagnosed COPD have a higher symptom burden, poorer quality of life, and worse general health status than age-matched healthy controls.5 The rate of exacerbations in undiagnosed COPD is approximately half that seen in patients with diagnosed COPD; however, they use healthcare services equivalently to treat exacerbation events as people with a prior diagnosis of COPD.5 They also have a higher risk of death compared to people without COPD.6,7

Patients with COPD are often diagnosed and begin treatment when the disease is already advanced. In fact, there is evidence showing that 44% of incident COPD cases were only diagnosed for the first time when they had a hospitalization related to COPD.8 This could perhaps be the reason why undiagnosed and untreated COPD patients show significant healthcare utilization and worse outcomes. Therefore, the question arises whether a specific COPD active case-finding strategy in the at-risk population could reduce the burden of underdiagnosis and improve the prognosis of the disease. Recently, a randomized clinical trial that used case-finding strategies to identify symptomatic individuals with undiagnosed COPD explored the effects of early treatment by a pulmonologist.9 A total of 38,353 persons were interviewed, 595 were found to have undiagnosed COPD or asthma and 508 underwent randomization. Regarding the severity of baseline airflow obstruction, the vast majority of undiagnosed COPD or asthma subjects 430/508 (84.6%) had mild to moderate airflow obstruction. The study showed that symptomatic individuals with undiagnosed COPD who received treatment by a pulmonologist and an educator had fewer respiratory illness events over one-year and showed improvement in symptoms, lung function, and quality of life.9 These results suggest that case-finding for symptomatic, undiagnosed COPD is feasible and that early treatment was associated with better clinical outcomes.

Case-finding strategies include active or opportunistic case-finding. Active case-finding involves the proactive search for people at increased risk for the condition, often based on the presence of symptoms, whereas opportunistic case-finding involves a passive approach to case identification, and screening of people that occurs when they present to healthcare services for reasons unrelated to the condition.

Different tools have been assessed for COPD case-finding (questionnaires, handheld devices, or a combination of tools).5 Results from different studies suggest that although the combined use of a questionnaire and a handheld device is the most effective strategy for identifying people at increased risk for COPD, questionnaires alone remain valuable tools for predicting COPD.5,10 Among the COPD risk questionnaires, the Study of Prevalence and Regular Practice, Diagnosis and Treatment, among General Practitioners in Populations at Risk of COPD in Latin America (PUMA questionnaire) is one that has external validations in different populations.11–13

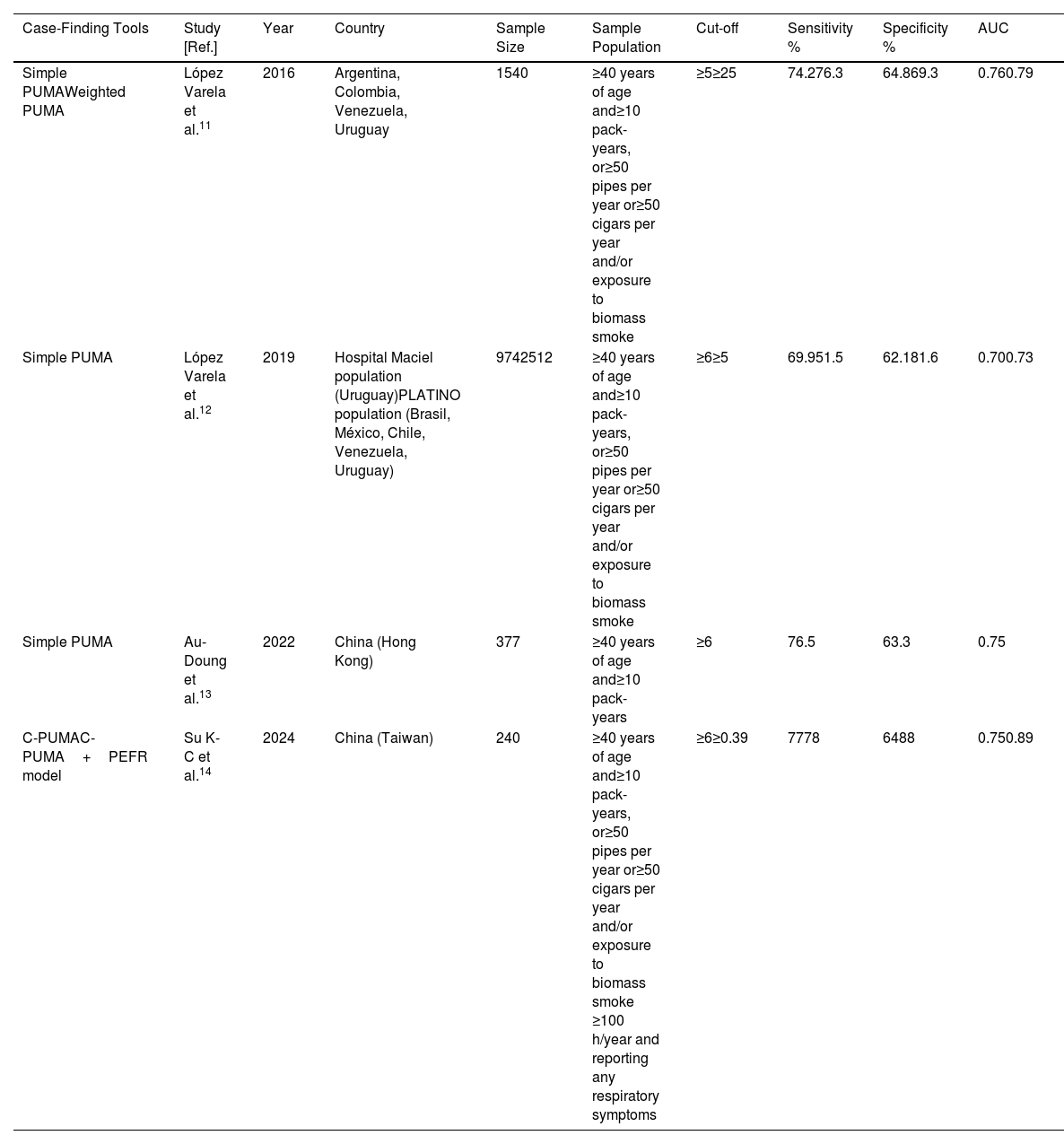

Table 1 shows the PUMA questionnaire performance of COPD case-finding. In Latin American population the PUMA questionnaire has shown acceptable diagnostic accuracy and predictive performance (AUROC=0.76, sensitivity/specificity/numbers needed to screen=74%/65%/4 at the cutoff score≥5).11 Additionally, in Hong Kong a translated Chinese PUMA version (for Cantonese) exhibited similar performance (AUROC=0.753; sensitivity/specificity=77%/63% at the cutoff score≥6).13 To date, no study has evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the combination of the PUMA questionnaire with handheld devices.

The PUMA Questionnaire Performance Results of COPD Case-Finding.

| Case-Finding Tools | Study [Ref.] | Year | Country | Sample Size | Sample Population | Cut-off | Sensitivity % | Specificity % | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple PUMAWeighted PUMA | López Varela et al.11 | 2016 | Argentina, Colombia, Venezuela, Uruguay | 1540 | ≥40 years of age and≥10 pack-years, or≥50 pipes per year or≥50 cigars per year and/or exposure to biomass smoke | ≥5≥25 | 74.276.3 | 64.869.3 | 0.760.79 |

| Simple PUMA | López Varela et al.12 | 2019 | Hospital Maciel population (Uruguay)PLATINO population (Brasil, México, Chile, Venezuela, Uruguay) | 9742512 | ≥40 years of age and≥10 pack-years, or≥50 pipes per year or≥50 cigars per year and/or exposure to biomass smoke | ≥6≥5 | 69.951.5 | 62.181.6 | 0.700.73 |

| Simple PUMA | Au-Doung et al.13 | 2022 | China (Hong Kong) | 377 | ≥40 years of age and≥10 pack-years | ≥6 | 76.5 | 63.3 | 0.75 |

| C-PUMAC-PUMA+PEFR model | Su K-C et al.14 | 2024 | China (Taiwan) | 240 | ≥40 years of age and≥10 pack-years, or≥50 pipes per year or≥50 cigars per year and/or exposure to biomass smoke ≥100 h/year and reporting any respiratory symptoms | ≥6≥0.39 | 7778 | 6488 | 0.750.89 |

Definition of abbreviations: AUC=area under the curve; PEFR=peak expiratory flow rate; PUMA=PUMA study questionnaire.

In this issue of the Archivos de Bronconeumologia, Kang-Cheng Su et al.14 assessed the accuracy of PUMA questionnaire in combination with peak expiratory flow rate to identify at-risk, undiagnosed COPD patients. The study included 2 stages: translating English to Chinese PUMA (C-PUMA) questionnaire with linguistic validation and psychometric evaluation, followed by clinical validation. C-PUMA demonstrated an acceptable diagnostic accuracy (AUROC=0.749) and the best cutoff score≥6. PUMA-PEFR model had higher diagnostic accuracy than C-PUMA alone (AUROC, 0.893 vs. 0.749, p<0.05), accounting for a sensitivity/specificity/numbers needed to screen of 77%/64%/3 and 79%/88%/2, respectively.14 A total of 78/240 (32%) were newly diagnosed COPD patients, who were categorized by GOLD grade 1 (37, 47%), grade 2 (34, 44%), and grade 3 (7, 9%) or by GOLD A (60, 8%), B (15, 2%), C (2, 3%) and D (1, 1%).14 This shows that the vast majority of the newly diagnosed COPD patients had, according to the GOLD stratification, mild to moderate severity of airflow obstruction and a low risk of exacerbation.

These results are of considerable interest because they illustrate again that existing symptom questionnaires such as PUMA, designed for COPD case-finding, are simple and relatively useful to accurately find undiagnosed COPD patients. They also indicate that combined modality using a questionnaire and a handheld device such as peak expiratory flow meters further improved diagnostic accuracy and is the most effective strategy for identifying people at highest risk for COPD. Active case-finding strategy identifies undiagnosed COPD patients with potential clinical benefits of early treatment.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.