It remains unclear if prematurity itself can influence post delivery lung development and particularly, the bronchial size.

AimTo assess lung function during the first two years of life in healthy preterm infants and compare the measurements to those obtained in healthy term infants during the same time period.

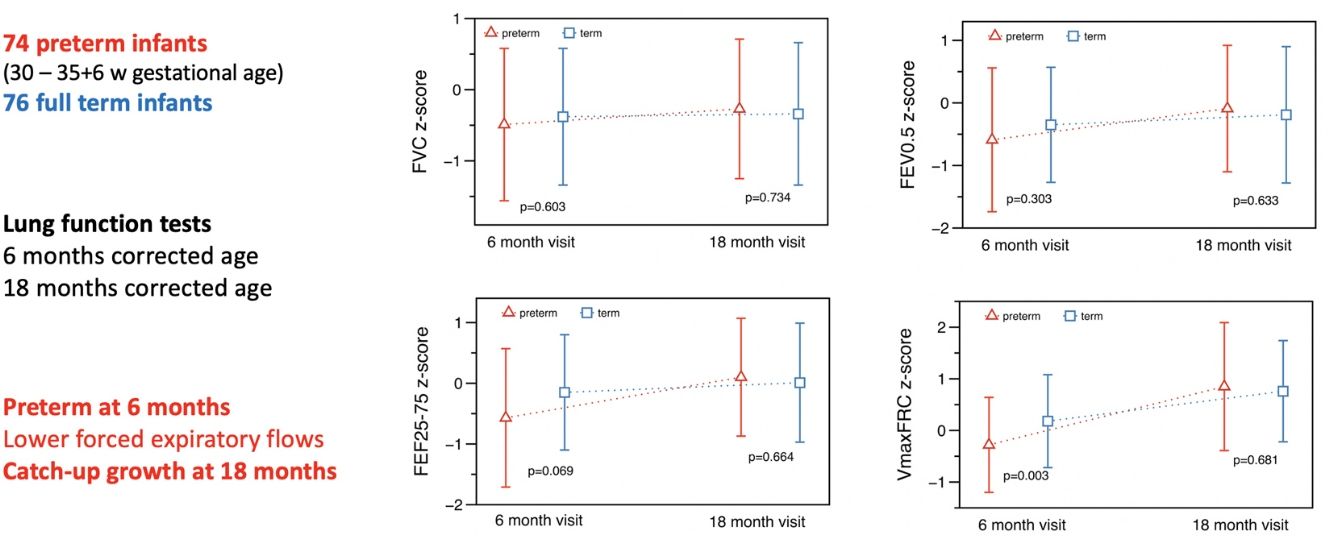

MethodsThis observational longitudinal study assessed lung function in 74 preterm (30+0 to 35+6 weeks’ gestational age) and 76 healthy term control infants who were recruited between 2011 and 2013. Measurements of tidal breathing, passive respiratory mechanics, tidal and raised volume forced expirations (V’maxFRC and FEF25–75, respectively) were undertaken following administration of oral chloral hydrate sedation according to ATS/ERS recommendations at 6- and 18-months corrected age.

ResultsLung function measurements were obtained from the preterm infants and full term controls initially at 6 months of age. Preterm infants had lower absolute and adjusted values (for gestational age, postnatal age, sex, body size, and confounding factors) for respiratory compliance and V’maxFRC. At 18 months corrected postnatal age, similar measurements were repeated in 57 preterm infants and 61 term controls. A catch-up in tidal volume, respiratory mechanics parameters, FEV0.5 and forced expiratory flows was seen in preterm infants.

ConclusionWhen compared with term controls, the lower forced expiratory flows observed in the healthy preterm group at 6 months was no longer evident at 18 months corrected age, suggesting a catch-up growth of airway function.

Todavía no está claro si la prematuridad por sí sola puede tener influencia en el desarrollo pulmonar tras el parto y, en particular, en el tamaño bronquial.

ObjetivoValorar la función pulmonar durante los 2 primeros años de vida en lactantes pretérmino sanos y comparar las medidas con las obtenidas en lactantes nacidos a término sanos durante el mismo periodo de tiempo.

MétodosEste ensayo longitudinal observacional valoró la función pulmonar en 74 lactantes pretérmino (30+0 a 35+6 semanas de edad gestacional) y 76 lactantes nacidos a término sanos como controles, que se seleccionaron entre 2011 y 2013. Se llevaron a cabo las mediciones de la respiración corriente, la mecánica respiratoria pasiva, los flujos espiratorios forzados a volumen corriente y con insuflación previa (V’maxFRC y FEF25-75, respectivamente) tras la sedación con hidrato de cloral siguiendo las recomendaciones de las ATS/ERS a la edad corregida de 6 y 18 meses.

ResultadosInicialmente se obtuvieron las medidas de función pulmonar de los lactantes pretérmino y los controles a término a los 6 meses de edad. Los lactantes pretérmino presentaron unos valores absolutos y ajustados (a la edad gestacional, la edad posnatal, el sexo, el tamaño corporal y los factores de confusión) menores para la distensibilidad pulmonar y la V’maxFRC. A los 18 meses de edad posnatal corregida, se repitieron las mismas mediciones en 57 lactantes pretérmino y 61 controles a término. Se observó una recuperación del volumen corriente, los parámetros de mecánica respiratoria, el FEV0,5 y los flujos espiratorios forzados en los lactantes pretérmino.

ConclusiónEn comparación con los controles a término, los flujos espiratorios forzados más bajos observados en el grupo de pretérminos sanos a los 6 meses no se observaron a los 18 meses de edad corregida, lo que evidencia un crecimiento de recuperación de la función de la vía respiratoria.

Prematurity is one of the most relevant factors determining respiratory health and survival of newborns. Long-term impairment of lung function (LF) in children born extremely preterm and in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) has been described.1–3 Previous results have showed a decrease in forced expiratory flows (FEF) in the first two years of life,4,5 which is related to a decrease in forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and in FEF between 25 and 75% of the forced vital capacity (FEF25–75%) in later years.6,7

Hoo et al.8 reported normal values of maximal expiratory flow at functional residual capacity (V’maxFRC) during tidal breathing in the neonatal period in preterm infants ≤36 weeks’ gestational age (GA), with a significant decrease in V’maxFRC at one year old.

Fakhoury et al.9 published that during the first 3 years of life, children with BPD continue to show airflow limitation (low V’maxFRC), while FRC measurements increased over time. Friedrich et al.10 found a normal FVC and a decrease in FEF in healthy preterm infants compared to term infants at a mean age of 10 weeks and such patterns was maintained at 64 weeks.11 These studies suggest that lung size increases adequately in preterm infants with somatic growth, however, airway function does not appear to develop at the same rate.

Preterm infants, and those affected by BPD, often present greater respiratory morbidity during the first years of life, with higher predisposition to lower respiratory tract infections and recurrent bronchitis, resulting in hospital admissions and high consumption of health resources.12

It is still not well known if prematurity itself can influence lung development and particularly the bronchial size. Diminished airway calibre could be a factor that explain the predisposition of preterm infants to develop wheezing bronchitis during the first years of life. In a recent study,13 respiratory symptoms in moderate/late preterms persisted during the first three years of life and were associated with abnormal LF tests.

Although there are many studies performed in preterm infants with associated pulmonary pathology,14–16 there are few studies7,8,10,11 that assess LF in preterm infants without associated respiratory pathology. LF testing in infants is difficult to perform and some measurements require sedation. The current international references for interpreting forced expiratory manoeuvres in infants have allowed a better interpretation of results.17

The main aim of this study was to obtain paired LF measurements during the first two years of life in healthy preterm infants (range of GA: 30w+0d to 35w+6d) and compare to those obtained in healthy term infants during the same time period, in order to assess whether an initial lower LF in preterms (most importantly, lower forced expiratory flows) would show catch up in the period observed. A secondary objective was to assess the feasibility of the techniques in this group.

MethodsThis was a prospective longitudinal, multicentre observational study, performed from June 2011 to December 2013 at three Spanish hospitals: Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona), Hospital Universitario Donostia (San Sebastián) and Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (Murcia).

Premature healthy infants born 30 weeks to 35 weeks+6 days gestational age (GA) and a control group of contemporaneous healthy term infants (≥37 weeks GA and birth weight ≥2.5kg) were recruited before 6 months postnatal age and followed until 18 months of age. GA was calculated from the date of maternal last menstrual period which was confirmed by an ultrasound scan performed before 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Preterm babies were recruited from their hospitals of birth. The control group was recruited from primary care centres in San Sebastian and Murcia and from hospitals in Barcelona. The babies who were recruited in primary care centres, were healthy babies without any respiratory symptoms or diseases. They were recruited at the 4-month check-ups. The babies who were recruited at the hospital in Barcelona, were healthy babies without any respiratory symptoms which attended the hospital because of the population based cystic fibrosis (CF) screening study, in which CF was ruled out with a negative genetic test and a normal sweat test.

None of the preterm infants required ventilatory support and had less than 24h supplemental oxygen following delivery. Infants with any other comorbidity or having ≥2 episodes of bronchitis or respiratory illness requiring hospitalisation before the age of 6 months, were excluded (see on-line supplement).

LF data from raised volume forced expirations obtained from some of the term infants were included in a multicentre study to develop reference ranges for forced respiratory manoeuvres in infants.17

Local Research Ethics Committee approval was granted and written parental consent obtained for all infants. The study was performed in accordance to the international ethical recommendations for research and clinical studies contained in the Declaration of Helsinki, standards of Good Clinical Practice, as well as the recommendations of the Spanish Agency for Medicines.

A perinatal history was compiled including family history of atopic disorders and passive smoking, data from pregnancy (gestational age, mother's age, ethnicity, number of foetuses), delivery data (mode, Apgar score, weight, length, sex) and any peri- and postnatal pathology. Respiratory symptoms or illnesses presented during the followed up checks were recorded at LF test visits and in every three months’ phone interviews.

Infant lung function testsInfants were tested at around 6 [Test 1, (T1)] and 18 months [Test 2, (T2)] corrected age (Table 1). LF tests were performed when infants were well or at least 3 weeks after any respiratory symptoms. Data were recorded during quiet sleep, in supine position, and after administration of chloral hydrate orally (50–100mg/kg).18,19 Oxygen saturation and heart rate were monitored before sedation and during testing. Weight and crown-heel length were measured using digital scales and a calibrated stadiometer. Both weight and length z-scores were calculated by means of WHO reference values.20

Comparison of background characteristics between preterm and term infants.

| Preterm(n=74) | Term(n=76) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boys, n (%) | 27 (36.5%) | 32 (42.1%) | 0.481 |

| Ethnicity, Caucasians, n (%) | 102 (96.2%) | 90 (96.8%) | 0.951 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks), median (IQR) | 34.0 (33–34.9) | 40.0 (39–40.6) | <0.001 |

| Birth weight (g), median (IQR) | 1955.0 (1750.0–2120.0) | 3270.0 (3000.0–3610.0) | <0.001 |

| Birth length (cm), median (IQR) | 44.0 (41.0–45.0) | 50.0 (49.0–50.0) | <0.001 |

| Oxygen therapy <24h, n (%) | 10 (13.9%) | 1.0 (1.3%) | 0.004 |

| Maternal age at delivery (y), median (IQR) | 35.0 (31.0–37.0) | 34.0 (31.0–37.0) | 0.450 |

| Maternal antenatal steroids, n (%) | 48 (64.8%) | 1 (1.3%) | <0.001 |

| Maternal history of atopy, n (%) | 10 (14.7%) | 17 (22.7%) | 0.224 |

| Maternal history of asthma, n (%) | 3 (4.4%) | 5 (6.7%) | 0.721 |

| Paternal smoking, n (%) | 24 (32.4%) | 24 (32.0%) | 0.955 |

| Paternal atopy, n (%) | 19 (26.4%) | 9 (12.2%) | 0.029 |

| Paternal asthma, n (%) | 16 (22.2%) | 7 (9.6%) | 0.037 |

| Test 1 | Pretermn=74 | Termn=76 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected age, weeks, median (IQR) | 25.4 (23.1–28.4) | 25.5 (22.8–27.7) | 0.319 |

| Weight, kg, median (IQR) | 7.23 (6.6–8.0) | 7.33 (6.81–8.04) | 0.441 |

| Weight, z-score, median (IQR) | −0.89 (−1.5 – 0.1) | −0.16 (−0.7 – 0.5) | <0.001 |

| Length (cm), median (IQR) | 66.0 (64.5–68.5) | 67.0 (65.0–68.0) | 0.783 |

| Length (z-score), median (IQR) | −0.84 (−1.9 – −0.1) | 0.21 (−0.5 – 0.8) | <0.001 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy, n (%) | 18 (24.3%) | 6 (7.9%) | 0.006 |

| Maternal current smoking, 6m, n (%) | 20 (27.4%) | 9 (11.8%) | 0.016 |

| Paternal current smoking, 6m, n (%) | 18 (24.7%) | 23 (30.3%) | 0.444 |

| One episode of bronchitis <6 months, n (%) | 13 (17.6%) | 10 (13.2%) | 0.411 |

| Test 2 | Pretermn=57 | Termn=61 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected age, weeks, median (IQR) | 78.3 (75.9–80.7) | 78.1 (75.1–80.9) | 0.992 |

| Weight, kg, median (IQR) | 10.32 (9.86–11.3) | 11.10 (10.54–11.62) | 0.008 |

| Weight, z-score, median (IQR) | −0.38 (−0.9 – 0.5) | 0.44 (−0.24 – 0.8) | <0.001 |

| Length (cm), median (IQR) | 80.7 (3.8) | 81.7 (2.7) | 0.099 |

| Length (z-score), median (IQR) | −0.60 (−1.5 – 0.2) | −0.10 (−0.8 – 0.8) | 0.001 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy, n (%) | 11 (19.3%) | 4 (6.6%) | 0.038 |

| Maternal current smoking, 18m, n (%) | 12 (21.1%) | 9 (14.7%) | 0.472 |

| Paternal current smoking, 18m, n (%) | 16 (28.1%) | 15 (24.6%) | 0.682 |

| One bronchitis 6–18 months, n (%) | 20 (35.1%) | 18 (29.5%) | 0.557 |

Gestational age: calculated according to maternal last menstrual period and ultrasound scan prior to 20 weeks pregnancy. Y: years, m: months, data presented as n (%) or mean (SD). Infant test age: corrected for gestation.

LF was assessed using the Jaeger MasterScreen BabyBody System (v.4.65; Carefusion, Hoechberg, Germany). Measurements of tidal breathing, single occlusion passive respiratory mechanics (total respiratory compliance, Crs, and total respiratory resistance, Rrs), tidal volume and raised volume forced expirations (tidal RTC and RVRTC, respectively) were undertaken (and in this order) according to ATS/ERS21 and international guidelines.22–24 The FVC, FEV0.5, FEV0.5/FVC and FEF at 50%, 75% and 25–75% of the FVC (FEF50, FEF75, FEF25–75) were reported from the “best” out of three acceptable forced expiratory curve with the biggest sum of FVC and FEV0.5.

All researchers were trained by the infant LF team at Respiratory, Critical Care & Anaesthesia section, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, United Kingdom. They developed identical protocols for LF testing, data analysis and quality control standards. AFH performed inter-laboratory visits for independent overread of results to ensure quality control.19,21

Statistical analysis and sample sizeDemographic and clinical data were collected on an electronic case report form (W3NEXUS, Fundació Institut Català de Farmacologia, Barcelona, Spain). Results were expressed as absolute values and converted to z-scores to adjust for gestation, postnatal age, length and weight at tests, and sex, in accordance to international reference equations.17,25,26 Corrected age was used for calculations of z-score in preterm infants.

Data were analysed by SAS® 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive data are shown as mean (SD) or median (IQR) for continuous variables, according to data distribution, and as n (%) for categorical ones. Comparisons between preterm and term infants were analysed using independent sample t-test or Mann–Whitney test for continuous data, and chi-square or Fisher exact tests where appropriate for categorical outcomes. A general linear multivariable analysis was performed to adjust for comparisons according to maternal tobacco use during pregnancy and need for oxygen therapy the first 24h of life. Statistical significance was set at a p value of <0.05.

It was estimated that 37 infants per group would provide 80% power to detect a difference of 0.67 z-scores (assuming SD 1 for both groups) between preterm and term infants for the LF variables.

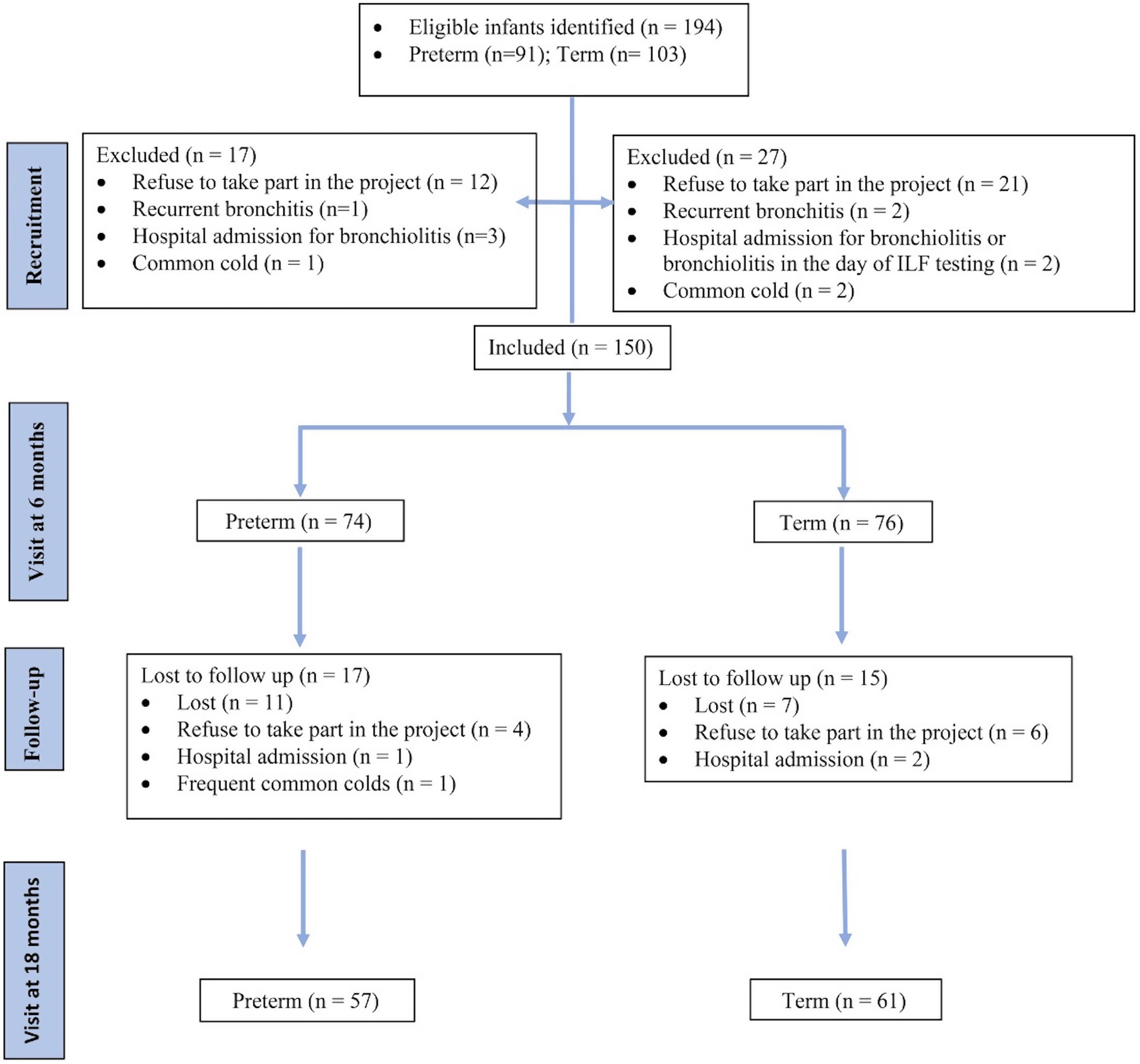

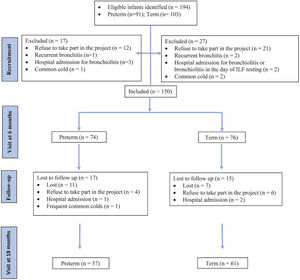

ResultsStudy subjectsA total of 194 infants were eligible (91 preterm and 103 term controls), of which 150 (74 preterm and 76 term) were included at the first visit at 6 months (Fig. 1).

A majority of the participants were Caucasians (96%). The mean (SD) GA was 33.8 (1.4) weeks in the preterm group and 39.7 (1.3) in the term group. There were no differences between groups in terms of sex, ethnicity or maternal age. More preterm infants received prenatal steroids and supplemental oxygen during the first 24h (Table 1). In preterm group there was a significantly higher percentage of exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy and up to 6 months corrected age, but not at 18 months (Table 1). In addition, there was a significantly higher percentage of paternal history of atopy or asthma in preterm group, but there were no differences in maternal history of atopy or asthma (Table 1).

At 6 months (T1), 74 preterm infants and 76 term controls attended for LFT (Fig. 1). There were no differences between the groups in weight (kg), length (cm) and vital signs (respiratory rate, heart rate and oxygen saturation) (Tables 1 and 2). There were significant differences in z-scores of length and weight between the groups (Table 1).

Vital signs during the lung function test of preterm and term infants.

| Test 1 | Pretermn=74 | Termn=76 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal heart rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 130.8 (12.0) | 128.3 (17.0) | 0.304 |

| Sedation heart rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 114.3 (10.9) | 115.2 (9.9) | 0.591 |

| Basal respiratory rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 39.7 (6.8) | 39.0 (16.6) | 0.756 |

| Sedation respiratory rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 33.1 (5.0) | 32.7 (12.7) | 0.778 |

| Basal SaO2, %, mean (SD) | 98.9 (1.1) | 98.7 (1.3) | 0.387 |

| Sedation SaO2, %, mean (SD) | 98.4 (1.2) | 98.7 (1.3) | 0.209 |

| Test 2 | Pretermn=57 | Termn=61 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal heart rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 127.3 (14.5) | 121.5 (16.2) | 0.004 |

| Sedation heart rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 103.3 (13.1) | 103.2 (5.5) | 0.952 |

| Basal respiratory rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 32.3 (6.3) | 32.3 (17.8) | 0.978 |

| Sedation respiratory rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 25.8 (3.1) | 27.2 (14.8) | 0.503 |

| Basal SaO2, %, mean (SD) | 98.8 (1.3) | 98.7 (1.7) | 0.949 |

| Sedation SaO2, %, mean (SD) | 97.5 (1.4) | 98.0 (1.5) | 0.062 |

SaO2: oxygen saturation in %, data presented as or mean (SD) of absolute values or z score.

At 18 months (T2), 57 preterm and 61 term infants were tested (Fig. 1). Weight and length z-score remained significantly different between the groups. Although basal heart rate was significantly higher in the preterm group, no differences were observed in other vital signs or in the history of bronchitis (Tables 1 and 2).

Infant lung function testingAlthough all infants attended for LF appointments at 6 months, some of the test could not be performed because either infants did not sleep post chloral sedation, or woke up during the test (4% for tidal RTC and 22.7% for RVRTC), and some data sets did not fulfil the technical or quality control criteria (0–4% for RTC and 29.7–38% for passive respiratory mechanics). The valid tests (%) at T1 were tidal breathing 89.3%, passive respiratory mechanics 43.3%, RTC 92%, and RVTC 55.3% and at T2 tidal breathing 92.2%, passive respiratory mechanics 59.3%, RTC 93.2%, and RVTC 81.4%. There were no differences between the proportion of valid test results (on-line supplementary Table S1).

Given the significant differences found between the groups regarding maternal smoking and the need for oxygen during the first 24h, the results were adjusted for both variables (Tables 3 and 4).

Technically acceptable lung function results at Test 1, ∼6 months.*

| Test 1 | Pretermn=74 | Termn=76 | z-Score difference(preterm−term)(95% CI) | p | Adjusted z-score difference(preterm−term)(95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tidal breathing tests (n) | 68 | 72 | ||||

| Respiratory rate, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.17 (0.86) | 0.14 (1.26) | 0.03 (−0.33; 0.39) | 0.877 | 0.09 (−0.30; 0.48) | 0.646 |

| Tidal volume, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.47 (0.86) | −0.59 (1.18) | 0.12 (−0.23; 0.47) | 0.498 | 0.11 (−0.26; 0.47) | 0.570 |

| tPTEF/tE, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.10 (0.86) | 0.02 (1.11) | −0.12 (−0.45; 0.21) | 0.480 | −0.18 (−0.53; 0.17) | 0.305 |

| Passive respiratory mechanics (n) | 26 | 40 | ||||

| Crs, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.08 (0.34) | 0.24 (0.51) | −0.32 (−0.53; −0.11) | 0.003 | −0.36 (−0.60; −0.12) | 0.004 |

| Rrs, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.14 (1.06) | −0.28 (1.27) | 0.41 (−0.16; 0.99) | 0.174 | 0.42 (−0.23; 1.07) | 0.202 |

| Tidal RTC (n) | 70 | 68 | ||||

| V’maxFRC, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.28 (0.92) | 0.18 (0.90) | −0.47 (−0.77; −0.16) | 0.003 | −0.43 (−0.76; −0.11) | 0.010 |

| Raised volume RTC (n) | 43 | 40 | ||||

| FVC, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.49 (1.07) | −0.38 (0.96) | −0.12 (−0.56; −0.33) | 0.603 | −0.04 (−0.51; 0.43) | 0.870 |

| FEV0.5, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.59 (1.15) | −0.35 (0.92) | −0.24 (−0.70; 0.22) | 0.303 | −0.20 (−0.68; 0.28) | 0.414 |

| FEV0.5/FVC, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.07 (0.68) | 0.07 (0.58) | −0.13 (−0.41; 0.14) | 0.340 | −0.16 (−0.44; 0.13) | 0.278 |

| FEF75, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.36 (1.14) | −0.11 (0.79) | −0.25 (−0.68; 0.18) | 0.249 | −0.31 (−0.75; 0.14) | 0.179 |

| FEF25–75, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.57 (1.14) | −0.15 (0.95) | −0.42 (−0.88; 0.03) | 0.069 | −0.46 (−0.93; 0.02) | 0.059 |

Adjusted difference for smoking mother during pregnancy and the need for oxygen in the first 24h of life.

SD: standard deviation; tPTEF/tE: time to peak tidal expiratory flow to expiratory time; V’maxFRC: maximal expiratory flow at forced residual capacity; Crs: compliance; Rrs: resistance; tidal RTC: tidal rapid thoracoabdominal compression; RVRTC: raised volume forced expiration; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV0.5: the forced expired volume at 0.5s; FEF75, FEF25–75: the forced expired flows at 50%, 75% and 25–75% of the FVC.

Technically acceptable lung function tests at Test 2 ∼18 months.

| Test 2 | Pretermn=57 | Termn=61 | z-Score difference(preterm−term)(95% CI) | p | Adjusted z-score difference*(preterm−term)(95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tidal breathing tests (n) | 54 | 55 | ||||

| Respiratory rate, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.09 (0.83) | −0.26 (0.83) | 0.35 (0.03; 0.67) | 0.030 | 0.38 (0.05; 0.70) | 0.025 |

| Tidal volume, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.07 (1.02) | 0.52 (0.86) | −0.46 (−0.81; −0.10) | 0.013 | −0.46 (−0.83; −0.09) | 0.017 |

| tPTEF/tE, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.29 (0.92) | −0.18 (1.14) | −0.11 (−0.50; 0.29) | 0.591 | −0.09 (−0.50; 0.32) | 0.675 |

| Passive respiratory mechanics (n) | 36 | 34 | ||||

| Crs, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.20 (0.43) | 0.20 (0.28) | 0.00 (−0.17; 0.18) | 0.984 | 0.01 (−0.18; 0.19) | 0.954 |

| Rrs, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.97 (0.89) | −0.71 (0.85) | −0.27 (−0.68; 0.15) | 0.205 | −0.27 (−0.70; 0.16) | 0.210 |

| Tidal RTC (n) | 52 | 58 | ||||

| V’maxFRC, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.85 (1.24) | 0.76 (0.98) | 0.10 (−0.31; 0.52) | 0.621 | 0.07 (−0.37; 0.50) | 0.762 |

| Raised volume RTC (n) | 43 | 53 | ||||

| FVC, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.27 (0.98) | −0.34 (1.00) | 0.07 (−0.34; 0.47) | 0.734 | 0.18 (−0.25; 0.60) | 0.407 |

| FEV0.5, z-score; mean (SD) | −0.09 (1.01) | −0.19 (1.09) | 0.10 (−0.33; 0.53) | 0.633 | 0.18 (−0.31; 0.53) | 0.601 |

| FEV0.5/FVC, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.11 (0.36) | 0.11 (0.36) | 0.00 (−0.15; 0.15) | 0.983 | −0.02 (−0.17; 0.13) | 0.508 |

| FEF75, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.10 (0.93) | 0.06 (1.04) | 0.04 (−0.36; 0.45) | 0.831 | 0.07 (−0.35; 0.48) | 0.750 |

| FEF25–75, z-score; mean (SD) | 0.10 (0.97) | 0.01 (0.98) | 0.09 (−0.31; 0.49) | 0.664 | 0.09 (−0.30; 0.49) | 0.645 |

Adjusted difference for smoking mother during pregnancy and the need for oxygen in the first 24h of life.

SD: standard deviation; tPTEF/tE: time to peak tidal expiratory flow to expiratory time; V’maxFRC: maximal expiratory flow at forced residual capacity; Crs: compliance; Rrs: resistance; tidal RTC: tidal rapid thoracoabdominal compression; RVRTC: raised volume forced expiration; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV0.5: the forced expired volume at 0.5s; FEF75, FEF25–75: the forced expired flows at 50%, 75% and 25–75% of the FVC.

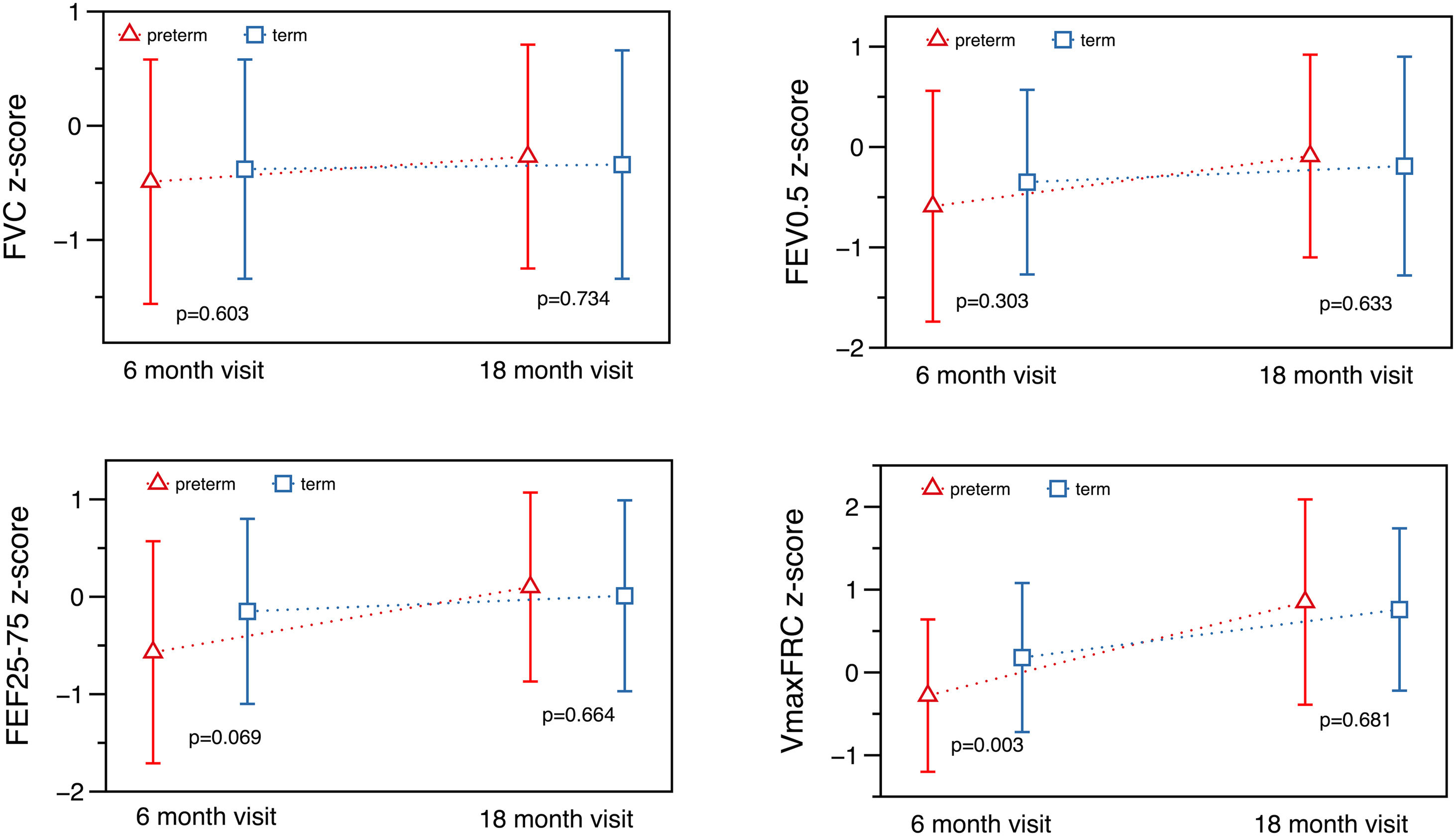

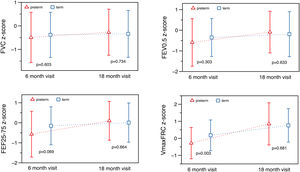

At T1 ∼6 months, significant differences were found in absolute values for total respiratory compliance (Crs), V’maxFRC and FEF25–75 (on-line supplementary Table S2). After adjusting for age, sex, weight and length, no significant differences were observed in tidal breathing measurements. However, there were differences in Crs as well as in V’maxFRC, which was significantly lower in the preterm group. Regarding RVRTC, no differences were observed, although there was a trend towards a lower FEF25–75 in preterm infants (z-score difference −0.46, p=0.059) (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

At T2 ∼18 months, significant differences were observed in respiratory rate and tidal volume, but there were no differences in Crs, Rrs, V’maxFRC or RVTC parameters (Fig. 2, Table 4 and on-line supplementary Table S3). The observed differences at 6 months of corrected age in Crs z-score, V’maxFRC z-score and FEF25–75 (absolute values) were no longer observed at 18 months (Tables 3 and 4 and on-line supplementary Table S4).

Preterm infants showed a significant increase, both unadjusted and adjusted for incidence of maternal smoking and the need for supplementary oxygen, between the two tests (Table 5 and on-line supplementary Table S5) in the z-score of tidal volume, Crs, Rrs, V’maxFRC, FEV0.5, FEF75 and FEF25–75. This increase was seen in term infants in respiratory rate, tidal volume and V’max FRC. Preterm infants had a significant improvement in respiratory mechanics and in FEF (V’maxFRC). Term infants had a greater increase in tidal breathing z-score (Table 5).

Catch-up of lung function tests between Test 1, ∼6 months and Test 2, ∼18 months. Adjusted difference for smoking mother during pregnancy and the need for oxygen in the first 24h of life.

| PretermAdjusted z-score difference(95% CI) | p | TermAdjusted z-score difference(95% CI) | p | Preterm−termAdjusted z-score difference(95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tidal breathing tests (n) | 54 | 55 | ||||

| Respiratory rate [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | −0.13 (−0.41; 0.13) | 0.339 | −0.37 (−0.63; −0.11) | 0.006 | 0.24 (−0.14; 0.61) | 0.216 |

| Tidal volume [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | 0.52 (0.23–0.81) | <0.001 | 1.04 (0.76; 1.32) | <0.001 | −0.52 (−0.93; −0.11) | 0.013 |

| tPTEF/tE [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | −0.14 (−0.44; 0.16) | 0.356 | −0.20 (−0.49; 0.08) | 0.164 | 0.06 (−0.35; 0.48) | 0.762 |

| Passive respiratory mechanics (n) | 26 | 34 | ||||

| Crs [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | 0.32 (0.13; 0.50) | 0.001 | −0.04 (−0.18; 0.11) | 0.627 | 0.35 (0.12; 0.59) | 0.004 |

| Rrs [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | −1.17 (−1.73; −0.61) | <0.001 | −0.42 (−0.88; 0.04) | 0.076 | −0.75 (−1.48; −0.03) | 0.042 |

| Tidal RTC (n) | 52 | 58 | ||||

| V’maxFRC [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | 1.06 (0.78; 1.34) | <0.001 | 0.59 (0.31; 0.86) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.08; 0.86) | 0.019 |

| Raised volume RTC (n) | 43 | 40 | ||||

| FVC [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | 0.17 (−0.19; 0.52) | 0.363 | 0.00 (−0.35; 0.36) | 0.978 | 0.16 (−0.34; 0.66) | 0.527 |

| FEV0.5 [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | 0.38 (0.01–0.75) | 0.049 | 0.20 (−0.17; 0.57) | 0.281 | 0.18 (−0.35; 0.70) | 0.506 |

| FEV0.5/FVC [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | 0.16 (−0.04; 0.36) | 0.114 | 0.08 (−0.12; 0.28) | 0.447 | 0.08 (−0.20; 0.36) | 0.568 |

| FEF75 [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | 0.37 (0.03; 0.70) | 0.033 | 0.28 (−0.04; 0.61) | 0.089 | 0.08 (−0.39; 0.55) | 0.728 |

| FEF25–75 [z-score; mean (95% CI)] | 0.53 (0.19; 0.86) | 0.003 | 0.25 (−0.09; 0.58) | 0.146 | 0.28 (−0.20; 0.75) | 0.247 |

SD: standard deviation; tPTEF/tE: time to peak tidal expiratory flow to expiratory time; V’maxFRC: maximal expiratory flow at forced residual capacity; Crs: compliance; Rrs: resistance; tidal RTC: tidal rapid thoracoabdominal compression; RVRTC: raised volume forced expiration; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV0.5: the forced expired volume at 0.5s; FEF75, FEF25–75: the forced expired flows at 50%, 75% and 25–75% of the FVC.

We compared the evolution of LF in preterm (30–35 6/7 GA) “healthy infants” with a contemporary term group at 6- and 18-months corrected age. Preterm infants had, at 6 months, lower absolute values of Crs and FEF (V’maxFRC, FEF25–75); this difference remained for Crs and V’maxFRC after adjusting for age, sex, body size, and confounding factors (mother smoking, need for oxygen in the first 24h). The more striking finding was that these differences disappeared at 18 months showing a catch-up in airway function as reflected by the measures of FEF. Preterm infants also showed catch-up in tidal volume, total respiratory compliance and resistances, FEV0.5 and FEF. At T2, term infants also showed some degree of catch-up in tidal volume (higher than preterms) and V’max FRC (lower than preterms).

At 6 months, the lower LF observed in the preterm infants with a normal lung size (normal FVC), is in concordance with previous studies.7,8,10,27,28 The lower respiratory compliance (Crs) has also been previously reported.7,8,10

The finding of a catch-up in LF in our study is in contrast with previous studies in preterm infants of a similar GA. Hoo et al.8 found a decline in V’maxFRC from the neonatal period to around 1 year of age in preterm infants suggesting for the first time that the prematurity per se causes a stop in the airways growth that could be a more important factor than any illness such as BPD. Friedrich et al. found that healthy preterm infants had normal vital capacities but decreased FEF in the first months10 that persisted at the 1-year follow-up evaluation.11 This tracking was also shown in another study including preterm infants with and without BPD.28 Lombardi29 and Verheggen30 found in very preterm infants that reactance was persistently low at 4 and 8 years of age.

Our work was designed to test the hypothesis that prematurity per se was associated with a deterioration of LF which tracks along the second year of life with somatic growth without showing a catch-up when compared with healthy term infants. Contrary with this hypothesis and some reported findings,11,28 we found that LF in our preterm infants caught up to normal values when compared with term controls by 18 months corrected age. At 18 months, we only observed differences in respiratory rate and tidal volume, probably due to the delayed maturation of the breathing pattern in the preterm infants. Lai et al.,7 in agreement with our results, reported that preterm infants without BPD, and also infants with mild to moderate BPD showed an improvement in LF during the second year of life while poor LF persisted in infants with severe BPD. Their observation and our results suggest that the reduced LF associated with prematurity during the first years of life, may catch-up with somatic growth provided there is absence of significant or additional lung damage caused by BPD leading to low LF that may persist to later life. Our infants were moderate/late preterms and had no/little insults in the first 18 months of life which resulted in no hospital admissions and mild wheezing episodes. The catch up observed would reinforce the importance of avoiding insults in the first two years of life, in order to have normal LF later on, as maybe prematurity could enhance the respiratory response to usual benign insults (such as viruses, pollution). Our results are in concordance with Pérez-Tarazona31 that showed that very extreme preterm infants with BPD had impaired LF that persisted into adolescence, but moderate/late preterm infants showed normal LF.

A study by Kotecha et al.32 found small differences in children born at 33–34 weeks and no differences in those born at 35–36 weeks.

Feasibility of LFT at this ageWe obtained tidal breathing and tidal forced expiration test data that met international standard in 90% of the infants at T1 and T2. These data were similar to those reported previously.7,8,30 However, only 35% preterm and 51% term infants performed adequate passive respiratory mechanics tests that met quality control criteria, and 58% preterm and 53% term produced acceptable RV tests at T1. At T2, feasibility improved to around 60% in passive respiratory mechanics and 80% in raised volume tests. The failures at T1 may be due to inadequate duration of quiet sleep, glottis narrowing and the difficulty in getting a good sedation level, as the results showed poor relaxation pattern for the calculation of passive mechanics, and early awakenings in RVRTC, or irregularities due to secretions or glottis narrowing that gave low quality results. At T2, quality of data improved, maybe due to improved experience in the staff, as it requires special training14 and also because of longer epochs of quiet sleep in infants during LF tests due to maturation of both groups.15 Since there is little literature published about feasibility data at this age, we have not much data to compare. Nevertheless, it seems a technique that in qualified hands, with proper technique and appropriate equations and availability of a control group,33,34 it could provide reliable results and offer a good opportunity for long term follow up until adult life.

The main strength of this study was the inclusion of a group of term infants33,34 tested at the same corrected age and in the same centres by the same team of staff using the same methodology and equipment. Collaboration with the UK group resulted in training being provided by experienced London investigators, as well as having independent quality control and over-read of data as the study progressed. Appropriate reference equations were used which facilitates an accurate interpretation of results.17,26 The main limitation was that we could not get reliable results in all the tests measured at 6 and 18 months and that there were some losses in the follow-up, although we fulfilled the calculated sample size for all parameters. We especially had a low success rate of the passive respiratory mechanics tests at T1 due to the infants not being in epochs of relaxed sleep long enough. As the LF test protocol was relatively long, and since we aimed to achieve a high success rate at the raised volume manoeuvres (i.e., airway function assessment), we decided to focus on the raised volume manoeuvres which were performed towards end of the test protocol. Another limitation was that we could not measure FRC and RV since we did not perform pletismography,35 which could have given us more information about lung volume and alveolarization in the preterm group.36

In conclusion, in our cohort at 6 months preterm healthy infants had lower forced expiratory flows and lower absolute values of respiratory compliance when compared with healthy term infants. However, these differences disappeared at 18 months of corrected age showing a catch-up growth of airway function.

FundingSupported by a non-restricted grant from AbbVie to Vall d’Hebron Research Institute.

Conflict of interestsAMG, have participated in Advisory Boards sponsored by Abbvie, Sanofi-aventis and Astra Zeneca, received institutional grants from AbbVie, received honoraria for lectures from Abbvie, and has received payment for conference registration and travel support from Novartis, Abbvie and Actelion. EGPY received institutional grants for research from Abbvie in the last 5 years. IMM has participated in Advisory Boards sponsored by GSK and received honoraria for lectures from them.

We thank the infants and their parents for participating in the research studies. We are very grateful to Janet Stocks, Sooky Lum, and Ah-Fong Hoo from Respiratory, Critical Care & Anaesthesia section, UCL-Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, United Kingdom, for their help with technical training and suggestions for the design of the study. We thank Xavier Vidal from Institut Català de Farmacologia, Barcelona for his help with statistical analysis of the data. AMG participate at ERN-LUNG.