Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a condition that carries high mortality and can be caused by sepsis or pneumonia.1 Histoplasmosis can cause a lung infection varying from mild pneumonitis to ARDS.2 This endemic mycosis can also cause disseminated infection and is catastrophic in immunocompromised patients.3 In transplant populations, it has an incidence of 1–3 cases per 1000 patients and is more prevalent in hepatic and renal transplants.4–6 Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is characterized by immune derangement of defective natural killer cells and macrophage overactivation. HLH is a rare complication of histoplasmosis but carries a mortality of up to 50%. Optimal treatment of infection-associated HLH is controversial and data is limited.7,8 Some physicians advocate for the use immunosuppression in addition to antifungal therapy, whereas others will only treat the underlying infection. Notably, current evidence suggests that this latter approach has less mortality.3,9–11

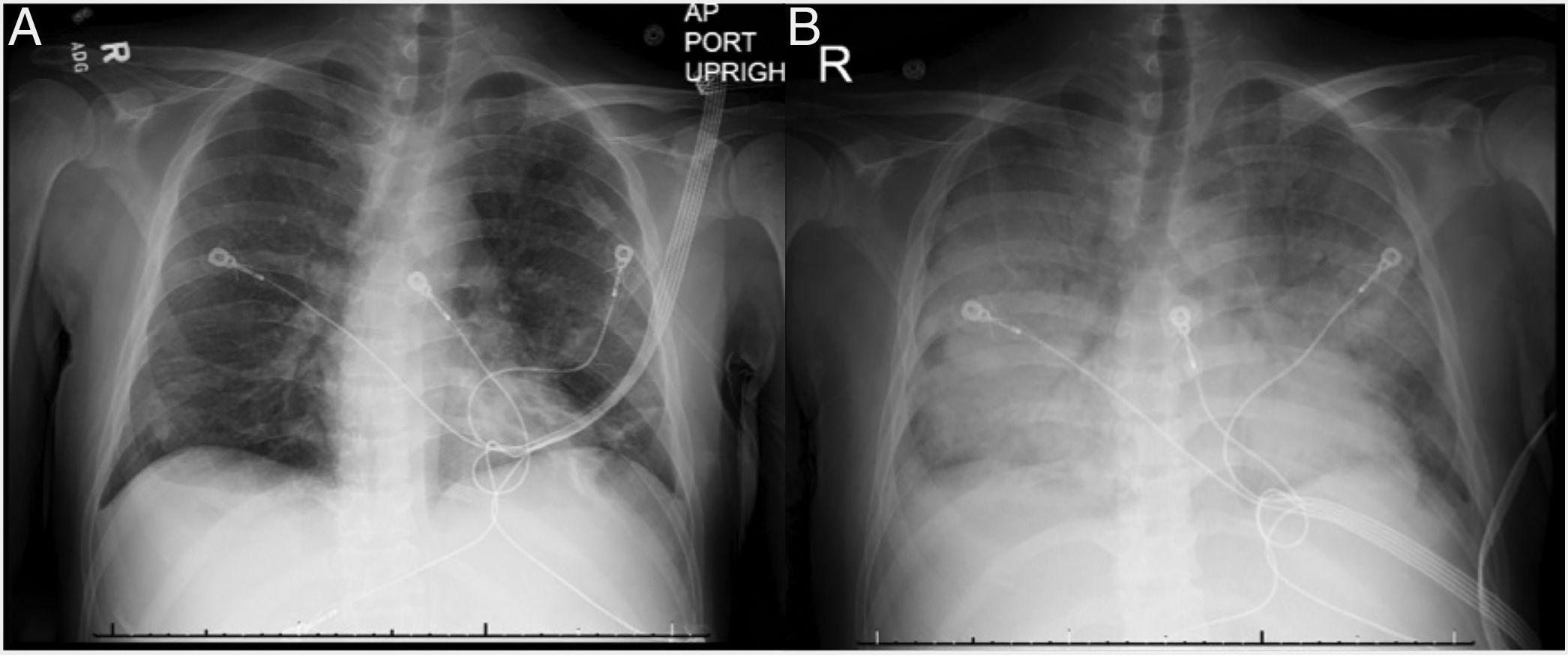

We present a case of a 46-year-old Korean male who underwent a deceased donor kidney transplant in 2014 secondary to diabetic nephropathy. He presented with vomiting, diarrhea and fever and was initially treated for viral gastroenteritis. Chest X-ray (CXR) on admission showed bibasilar linear infiltrates (Fig. 1A). His clinical status rapidly deteriorated and he was admitted to the intensive care unit and was started on low-dose vasopressors. Patient's hemodynamics continued to worsen with respiratory failure requiring high-flow nasal cannula due to hypoxemia. He rapidly developed ARDS and required intubation with low-tidal volume ventilation and paralytics. Chest X-ray revealed diffuse bilateral alveolar infiltrates with air bronchogram (Fig. 1B) and chest computed tomography revealed tree-in-bud infiltrates and splenomegaly. Laboratory data was notable for pancytopenia, transaminitis, ferritin of 16,624ng/mL, elevated LDH, normal triglycerides and a positive urine and serum Histoplasma antigen. He had several environmental and animal exposures including bats, rats, animal droppings and mold along subway tunnels. Work-up including acid-fast Bacilli smear and culture, hepatitis panel, Bartonella, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Legionella, Cryptococcus, Parvovirus, Human Herpes Virus 6, Adenovirus, Epstein-barr Virus and Cytomegalovirus polymerase chain reaction tests were negative. Bronchoalveolar lavage revealed numerous fungal organisms in the form of budding yeasts without evidence of pseudohyphae, consistent with Histoplasma Capsulatum. Culture data confirmed the diagnosis. The patient rapidly improved and was successfully extubated after starting amphotericin B, followed by itraconazole. Soluble IL-2 receptor came back elevated (14,150pg/mL) a few days later. Tacrolimus and mofetil mycophenolate had been initially stopped due to worsening renal function but were restarted before discharge. The patient was fully recovered at 6-month follow up.

This case highlights that patients with significant immunosuppression can develop severe ARDS secondary to histoplasmosis.2 This has mainly been described in patients with HIV who can also develop HLH as a rare complication.3 The current treatment of primary HLH is based on immunosuppression12 but there is not consensus on the treatment of infection-associated HLH.8 Moreover, the literature in organ transplants patients is limited. One study reported less mortality in patients who do not receive additional immunosuppression, although only a small number of patients were included in that study.3 Our patient met five criteria for HLH, including fever, splenomegaly, pancytopenia, high ferritin level and elevated IL2 soluble receptor. He had an excellent response to treatment targeting histoplasmosis without the use of steroids or further immunosuppression. In the largest case series of 11 cases of patients with histoplasmosis-induced HLH, the mortality was 46% at 30 days and 63% at 90 days, with increased mortality up to 80% in the group who received immunosuppression.3 The study included nine patients with HIV and two with renal transplants.3 Further evidence of HLH and histoplasmosis in kidney transplant is scarce. Nieto et al. report two cases, one successfully treated with antifungals alone and one with a fatal outcome after receiving increased immunosuppression.9 Similarly, Contreras et al. report a renal transplant patient who successfully responded to antifungal therapy alone.10 Lo et al. describe a successful experience of two kidney transplant patients who received only dual antifungal therapy with amphotericin and itraconazole.11 Notably, there were no acute rejections in spite of decreased immunosuppression. Therefore, it should be highlighted that limiting immunosuppression may be necessary if patients are refractory to antifungal therapy to ensure complete resolution of Histoplasmosis infection. In our patient, we held immunosuppression on admission and he did not experience any complications. Limitations related to the small number of patients and the possibility of treatment bias in patients who were sicker should be considered. Prospective treatment studies would be ideal, but they are unlikely given the rarity of this disease. In conclusion, our case adds to the limited literature that suggests that treatment of an underlying infection in HLH alone could lead to rapid resolution of this otherwise lethal disorder. Further data is needed to define the role of immunosuppression in treating this condition.