Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) is a rare condition characterized by an eosinophil infiltration of pulmonary parenchyma, which leads to an acute respiratory illness. It can be idiopathic or secondary to various agents, including infectious diseases.1 We describe a case of AEP related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, expressed as a recurrence of respiratory symptoms after initial recovery from Covid-19 pneumonia.

A 61-year-old man without relevant medical history arrived at the emergency room with dyspnea, having started with fever and cough 2 weeks before. He did not smoke and denied other toxic use. A chest x-ray showed bilateral peripheral opacities and a nasal-oropharynx PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was positive. Mild elevation of ferritin, CRP and IL-6 was observed. The patient was admitted to the hospital with the diagnosis of Covid-19 pneumonia and treatment began with hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and lopinavir/ritonavir (following the current hospital protocol at that moment), plus oxygen therapy at an initial FiO2 of 28%. Patient's clinical and respiratory condition progressively improved and he was discharged after 5 days.

He came back to the hospital after one week because of recurrence of dyspnea and mild fever. New bilateral consolidations were observed in the chest X-ray, with no major changes in inflammatory parameters compared to previous admission. Slight elevation of neutrophils was observed, with normal eosinophil count (200cells/ml). The PCR for SARS-CoV-2 at this time was negative. With the suspicion of infectious vs inflammatory complication, ceftriaxone and iv methylprednisolone 60mg per day were started, and the patient was readmitted to the hospital.

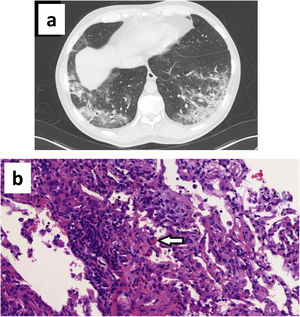

The CT scan showed bilateral subpleural ground glass opacities with areas of consolidation, with an air bronchogram sign and associated bronchiectasis (Fig. 1a). A bronchoscopy for bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsy was performed on the fifth day after admission. Bacterial cultures and bacilloscopy of BAL, bronchial aspirate and biopsy were negative. SARS-CoV-2 PCR was positive in bronchial aspirate but negative in BAL. The differential cell count in BAL fluid had 50% macrophages, 30% lymphocytes, and 20% polymorphonuclears (including 5% eosinophils). The biopsy showed a prominent mixed infiltrate in interstitium and alveoli with numerous eosinophils, compatible with partially treated AEP (Fig. 1b).

(a) CT scan showing ground glass opacities with areas of consolidation, air bronchogram and bronchiectasis; (b) Hematoxylin eosin staining (40× magnification) showing prominent lymphoplasmacytic interstitial infiltrate with numerous eosinophils. Alveoli infiltrate with mixed cellularity (lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, foamy macrophages, fibroblasts). Note one macrophage with phagocytized eosinophil granules (arrow).

The patient completed one week of hospitalization, with both clinical and radiological improvement, and he was discharged continuing prednisone at a dose of 30mg per day. During follow up in outpatient consultation the study was completed with HIV and Strongyloides stercoralis serology, as well as ANA and ANCA antibodies, which were all negative. A CT scan was repeated after one month, showing resolution of consolidation areas with persistence of minimum ground glass infiltrates. At this time, complete functional recovery was objectified with a forced vital capacity of 141% with no obstructive espirometric pattern, a carbon monoxide diffusion capacity of 84%, and absence of oxygen desaturation in the six minute walking test.

AEP presents as an acute respiratory illness, whose symptoms appear within days or weeks. Severity can go from mild disease to acute respiratory distress syndrome, with potential progression to death. It can be idiopathic or secondary to inhalational toxics, drugs or infections.1

Diagnosis is challenging, especially during the current pandemic situation, since the clinical picture might resemble COVID-19 disease.2 Diagnosis is based on clinical and laboratory criteria, with a leading role of cytological analysis of BAL fluid, where eosinophils usually represent more than 25% of the cells. Lung biopsy is not usually required, unless an alternative diagnosis needs to be excluded. Management consists in cessation of exposure to underlying causes when identifiable, and treatment with systemic glucocorticoids in most cases. Clinical and radiological response is usually rapid and complete without any long term sequelae.1

The diagnosis of AEP in our patient was established through biopsy which confirmed pulmonary eosinophilia. However, as a main limitation in this case report, the BAL fluid differential count only showed 5% of eosinophils. This low percentage could be related to the fact that bronchoscopy was performed 5 days after initiation of glucocorticoids. As seen in other AEP case reports, eosinophils in BAL fluid return to normal as the illness resolves, in some cases within a few days after initiation of treatment so steroids could have influenced this result.3,4 Another feature supporting AEP diagnosis in our patient is the rapid clinical and radiological response, considered an important diagnostic criterion.

Regarding possible etiologies of AEP in this case, SARS-CoV-2 would be suggested as a first option. The infection was confirmed by PCR technique and the initial clinical picture was typical. At readmission, recurrence of symptoms with worsening of pulmonary infiltrates would recall the inflammatory phase in Covid-19 disease, but the biopsy results were unusual. Previous histopathological reviews of Covid-19 pneumonia have not reported the presence of eosinophils as a common finding, and the role of pulmonary eosinophilia does not seem to be relevant in the physiopathology.5–7 Therefore, we could suggest our case as a rare eosinophilic complication differentiated from typical Covid-19 disease. Although parasites and fungus are the infectious agents most frequently associated with AEP, other viruses such as Influenza A H1N1 have been reported, so an eventual association with SARS-CoV-2 could also be possible.8,9

Other potential causes of AEP would be related to the treatment that our patient had received. A few cases of drug induced eosinophilic pneumonia have been reported associated to azithromycin and antimalarial drugs, including chloroquine, but none to lopinavir/ritonavir.10,11 Against this possibility, there is the fact that patient's clinical condition was improving while on these drugs, whereas symptoms reappeared once the treatment was over.

We finally want to highlight the importance of having a clinical suspicion of AEP when patients affected by Covid-19 pneumonia experience a recurrence or worsening of symptoms, since early glucocorticoid therapy would avoid further complications. In these cases, BAL should be ideally performed before instauration of treatment for proper diagnosis.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.