Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic disease of unknown etiology represented by 2 predominant forms: ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.1 Extraintestinal manifestations occur in 21%–47% of patients with IBD,2 some of which are well defined and parallel the course of the intestinal disease. Pulmonary involvement, however, presents a heterogeneous time frame that makes it difficult to recognize as a symptom associated with bowel disease.3 IBD is associated with respiratory disease in up to 40% of patients and bronchiectasis is the most common disorder.4,5 Although systemic corticosteroids tend to improve respiratory symptoms in these patients, especially cough,6 response to this treatment is erratic in the case of bronchiectasis, requiring additional therapeutic strategies to adequately control symptoms.

Here we report the case of a 52-year-old woman with ulcerative colitis and bronchiectasis who had resolution of her respiratory symptoms after control of the IBD with tofacitinib.

The patient, an ex-smoker for 27 years, had been diagnosed with extensive ulcerative colitis in 2011. Her initial treatment history showed failure of thiopurines and 2 anti-tumor necrosis agents (infliximab and golimumab), and corticosteroid dependence. In April 2016, treatment was started with vedolizumab (anti-integrin α4β7) with initial partial response, which gradually improved. After 18 months (October 2017), vedolizumab treatment was intensified due to clinical worsening of the colitis.

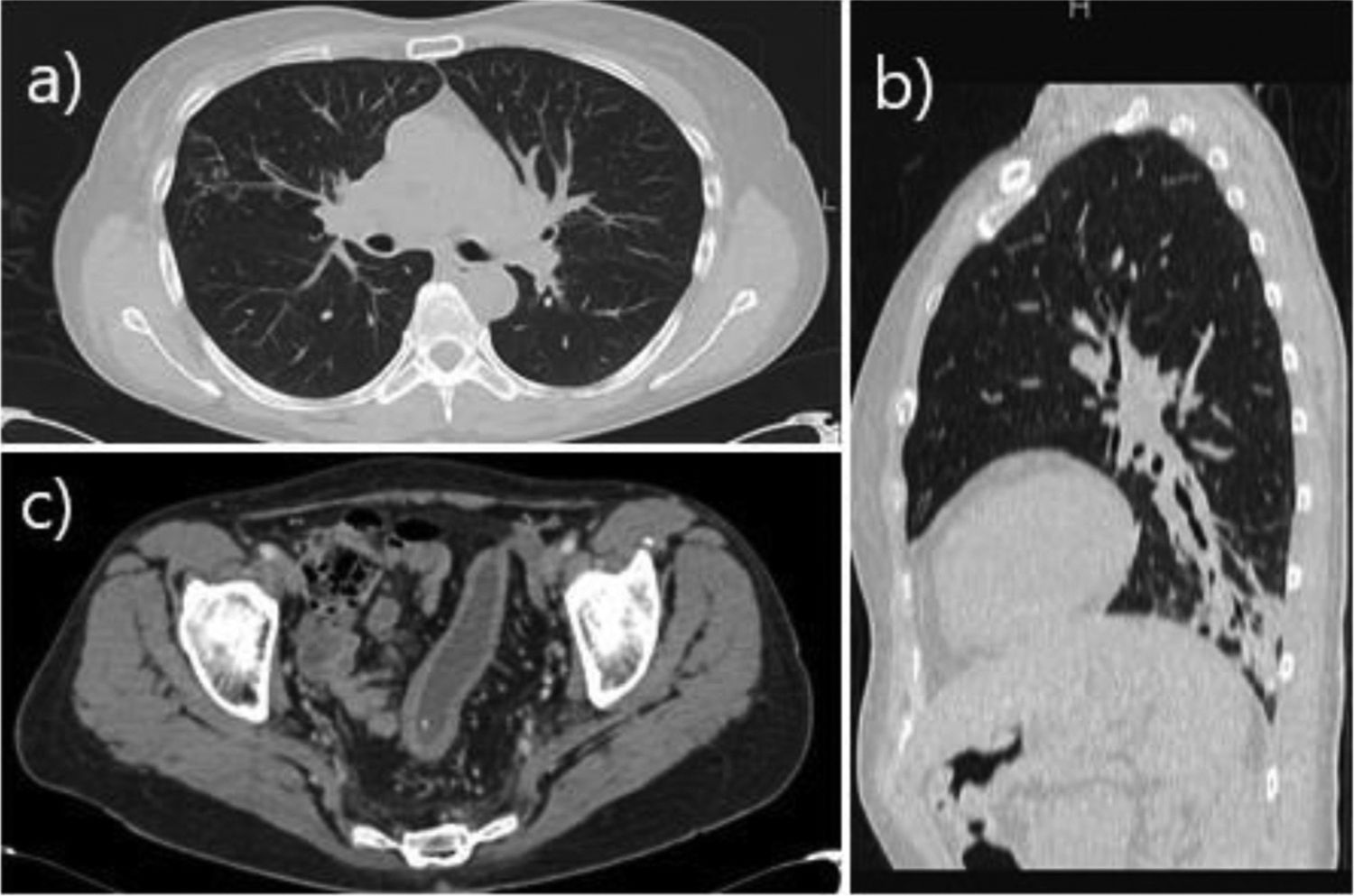

The patient was asymptomatic from a respiratory point of view until October 2017, when she began to experience cough and expectoration. High-resolution chest computed tomography (CT) revealed the presence of cylindrical bronchiectasis in the left lower lobe (Fig. 1). No potentially pathogenic microorganisms were isolated in sputum cultures. From a functional point of view, spirometry showed a moderate-to-severe obstructive pattern (FEV1 1.81 L [59%]; FVC 3.09 L [77%]; FEV1/FVC: 0.59). In January 2018, she was assessed at the bronchiectasis clinic: the patient reported purulent expectoration of approximately 40 cc per day and had required 4 courses of antibiotics since October 2017. Accordingly, treatment was started with inhaled bronchodilators (ipratropium bromide and salbutamol) and hypertonic saline 6% to facilitate expectoration of secretions. One month after treatment initiation (February 2018), due to the persistence of purulent expectoration—albeit to a lesser extent than prior to the use of hypertonic saline—nebulized ampicillin was added in order to keep the patient free from exacerbations.

(a) Axial CT slice in pulmonary window showing micronodular opacities with tree-in-bud distribution in the lateral segment of the middle lobe, consistent with infectious airway involvement. (b) Sagittal CT reconstruction in pulmonary window showing peripheral opacity of infectious appearance in the left lower lung associated with bronchiectasis. (c) Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan of the pelvis in soft tissue window, showing sigmoid colon wall thickening and submucosal edema of chronic appearance, related with the patient’s inflammatory bowel manifestation.

In April 2018, following evidence of clinical deterioration and persistence of moderate endoscopic colitis activity, compassionate use of tofacitinib was requested.

In July 2018 (6 months after the start of nebulized treatment and after 3 months on tofacitinib), the patient did not report expectoration or further exacerbations. In view of this clinical improvement, she decided to discontinue treatment of the respiratory disease, remaining completely asymptomatic until her last check-up (May 2019). In terms of gastrointestinal symptoms, the patient has been in clinical remission since commencing tofacitinib.

Extraintestinal manifestations of IBD can affect all organs of the human body and are most often associated with Crohn’s disease.7 In turn, they may be the result of the IBD inflammatory process or have a non-specific origin, which means that they do not always respond to treatment.8

The most common respiratory manifestations are due to involvement of the central airways, bronchi and interstitium,9 and bronchiectasis is the most commonly associated respiratory disease.5 Patients with IBD have been shown to develop more respiratory symptoms than the general population.5 Although the etiology of this association is unknown, it could be due to the common embryonic origin of the respiratory and intestinal mucosa and their response to different antigens.10

As evidenced in previous studies, the onset of respiratory symptoms differs widely among patients: it may occur prior to, concomitant to, or after the detection of IBD, and even after it is inactivated.11 In our case, the patient's lung disease started simultaneously with an intestinal flare-up.

In general, patients present symptoms such as cough with purulent expectoration that does not respond to antibiotic treatment. Sputum cultures do not usually provide clinically relevant data, as in our case.11

There is no solid scientific evidence of the effectiveness of the pharmacological or surgical treatment of IBD in the progression of respiratory disease.12 There is one case report of a patient diagnosed with ulcerative colitis who developed bronchiectasis after surgical treatment of the underlying disease,9 which could support the theory of the aforementioned common embryonic origin. The only drug with which improvement of the respiratory disease has been described (in clinical cases only) is infliximab.13

Tofacitinib, an oral JAK 1–3 inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in adults in 2018,14 so in our case (2017), we had to apply for compassionate use. Its major advantage with respect to infliximab is its posology, since the latter requires intravenous administration.

In terms of treatment, disease-modifying anti-IBD drugs (DMAID) are not recommended for the specific management of respiratory involvement. Oral and inhaled corticosteroids remain the treatment of choice for respiratory manifestations,15 and should be maintained until symptomatic and functional improvement. In our case, since the patient presented simultaneous onset to the intestinal flare-up, coupled with the need for several courses of antibiotics due to superimposed infection of the bronchiectasis, we decided to initiate treatment with hypertonic saline instead of corticosteroids, hoping for good control, after stabilization of the intestinal flare-up.

As we can see, there is no evidence that the use of DMAIDs improves respiratory symptoms. We present the first case in which the use of tofacitinib resulted in complete resolution of respiratory symptoms in a patient with a history of ulcerative colitis. In view of the clear improvement, the patient decided to discontinue inhaled therapy and remained with adequate control of both the respiratory and intestinal disease.

In conclusion, studies with greater scientific evidence are needed to identify the relationship between the treatment of IBD with tofacitinib and the improvement in respiratory manifestations such as bronchiectasis, which greatly affects quality of life in these patients. It is important to raise awareness of the association of these diseases to improve their detection and enable early and appropriate multidisciplinary management.

Please cite this article as: León-Román FX, et al. Colitis ulcerosa y bronquiectasias: ¿el tratamiento con tofacitinib podría repercutir en los síntomas respiratorios? Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:176–178.