The utility of endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) guided transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) for patients with suspected sarcoidosis is well established. However, the reported diagnostic yield has varied from 80 to 94%.1–3 Many new EBUS needles have been introduced in the last 5 years. Tyan et al. and this author had separately published small series with reported yield of 93% using a 19-G needle for sarcoidosis.4,5 One of the drawbacks of these studies was small sample size. Despite introduction of this particular device almost 4 years ago, larger studies detailing performance of this needle for granulomatous inflammation or lympho-proliferative disorders have not been published. We would like to share diagnostic and safety data from our experience over 3 years in a community hospital with selective use of this instrument.

Electronic medical record system was retrospectively reviewed to identify patients who underwent EBUS-TBNA between July 2016 and July 2019. This study was approved by Institutional Review Board (Maine General Medical Center, Augusta, ME, USA). Medical records were reviewed to identify needle gauge, sampling location, diagnosis and any immediate complication from the procedure. Patients in which only 19 G needle (ViziShot FLEX 19G needle, Olympus America, Redmond, WA, USA) was used were selected. Available follow up records were reviewed.

EBUS procedureAll EBUS included in data analysis were performed under general anesthesia (Propofol infusion with or without remifentanil) with endotracheal intubation by anesthesia providers. White light bronchoscopy was performed prior to convex probe EBUS survey in all patients (Olympus BF-1TH190, BF-1THQ190; Olympus BF-UC180F and ultrasound image processor EU-ME1; Olympus America). 19-gauge needle was preferentially used in patients with clinical suspicion of sarcoidosis, lymphoma or for cancer restaging. The designated lymph node (LN) was punctured under direct EBUS guidance. Suction was used with all passes unless significant vascularity and/or bleeding was noted with the preceding passes. At least 4 passes were done at each station. An additional pass was done if no visible aspirate was obtained on any of the attempted aspirate. Part of the aspirated material from first±second pass was smeared on to glass slides. Remainder of the aspirate was discharged into 95% ethanol for cell block preparation by using stylet or blowing air. Smears were air-dried and fixed in 95% ethanol. Rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) was used in all cases in order to ensure sampling adequacy. Adequate cell material was defined as presence of lymphoid tissue of adequate cellularity or sufficient for a specific diagnosis, such as the presence of noncaseating granulomas without necrosis. TBNA was terminated if latter was reported and subsequent biopsies performed at discretion of bronchoscopist. Bronchioalveolar lavage, transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) and endobronchial biopsy were performed in a standard fashion and samples fixed in formalin for histopathological examination. Post-procedure chest X-ray was performed in all patients undergoing TBLB.

Information about needle size was available for 436 patients out of 577 patients who underwent EBUS during the study period. Only 19 G needle was used in 72 patients. Final pathological diagnosis based on biopsy included granulomatous inflammation (n=39), benign lymph node (n=16), metastatic malignancy (n=9), lympho-proliferative disorder (n=7) and non-diagnostic (n=1). The approximate size of sampled lymph nodes varied from 8 to 40mm. Sarcoidosis was suspected in 40 patients in the 19 G needle group and confirmed with flexible bronchoscopy in 39. Females constituted 60% (24) of the patients. Average age was 52 years (range 26–79 years).

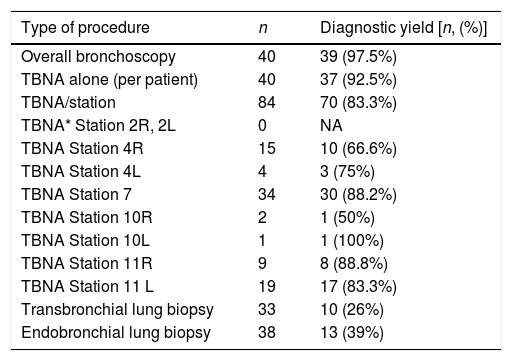

Diagnostic yield of EBUS-TBNA and TBLB for sarcoidosis was 97.5% (39/40). The diagnostic yield of TBNA alone for pathological confirmation of granulomatous inflammation was 92.5% (37/40). TBLB was diagnostic in 2 cases without a TBNA diagnosis. Eighty-four LNs were sampled in the sarcoidosis group. Median number of LN sampled per patient was 2. The diagnostic yield for sarcoidosis per sampled LN was 83.3% (70/84). Station 7 LN was most frequently sampled (n=34) with a diagnostic yield of 88%. The diagnostic yield of various locations and biopsies for sarcoidosis is presented in Table 1. All patients with unexplained benign lymphadenopathy were followed up for at least 6 months.

Diagnostic yield for granulomatous inflammation and location of sampling.

| Type of procedure | n | Diagnostic yield [n, (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| Overall bronchoscopy | 40 | 39 (97.5%) |

| TBNA alone (per patient) | 40 | 37 (92.5%) |

| TBNA/station | 84 | 70 (83.3%) |

| TBNA* Station 2R, 2L | 0 | NA |

| TBNA Station 4R | 15 | 10 (66.6%) |

| TBNA Station 4L | 4 | 3 (75%) |

| TBNA Station 7 | 34 | 30 (88.2%) |

| TBNA Station 10R | 2 | 1 (50%) |

| TBNA Station 10L | 1 | 1 (100%) |

| TBNA Station 11R | 9 | 8 (88.8%) |

| TBNA Station 11 L | 19 | 17 (83.3%) |

| Transbronchial lung biopsy | 33 | 10 (26%) |

| Endobronchial lung biopsy | 38 | 13 (39%) |

*TBNA, transbronchial needle aspiration; Lymph node stations are defined as per IASLC lymph node map.8

No procedure related adverse events were noted. One anesthesia related adverse event occurred. We had two instances of sheath breakage from the needle as previously reported5 without any damage to the bronchoscope.

The current review adds to the growing literature on the utility of EBUS TBNA for establishing the diagnosis of granulomatous inflammation in patients with mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. The randomized controlled studies published using this needle were directed toward malignant lymphadenopathy.6 Therefore, we would like to share our 3-year experience and diagnostic data with selective use of this needle. The needle is marketed as being more flexible as compared to other needles and authors experience is in-line with prior published reports.4 We continued to observe a high diagnostic yield for sarcoidosis. However, opposed to our initial findings where we did not see an incremental benefit from TBLB,5 in this continuation series 2 patients (5%) were diagnosed solely on basis of TBLB. Both these patients had firm LNs with scant aspirate. One patient was clinically diagnosed with sarcoidosis based on response to steroid despite benign cytology and the procedure was considered non-diagnostic.

No patient in this series required additional tissue sampling for diagnosis of granulomatous inflammation. While this review was directed toward sarcoidosis patients, it was noted by the author that many of these patients were referred for evaluation of lymphoma given the overlap in symptoms and radiographic findings. We were able to establish a diagnosis of lympho-proliferative disorder in 7 patients but 57% (4/7) required repeat procedures for subtyping.

The sheath breakage events were reported to the manufacturer and no manufacturing defect was identified. In both the instances, lymph nodes were firm and lymph node puncture was deemed challenging. We speculate that the incidents could be related to the excessive torsional strain on the needle.

Since the introduction of this needle, newer needles have been marketed with the promise of providing core specimens. There is a shift toward endoscopic needle biopsy over aspiration in the gastroenterology literature.7 Similar trend might be noted in pulmonary medicine in coming years as the need for tissue increases. In the absence of comparative data, good performance data and familiarity with design might be a factor for some proceduralists to continue using this needle. It is possible that different attributes of each needle might make them better suited for different pathologies. We share our data to add to the scant available literature about using this needle for granulomatous lymphadenopathy.