As of July 06, 2020, 251,789 confirmed cases of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection and 28,388 (11.3%) deaths attributed to SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19) have been recorded in Spain.1 However, as of May 8. 2020, only 2158 cases and 7 (0.3%) deaths among Spanish patients aged less than 19 years of age had been reported.2 The largest series to date agree that most children and adolescents infected with SARS-CoV-2 show a milder clinical course than adults, with severe COVID-19 cases occurring almost exclusively in patients with underlying conditions.3,4 Recently, a pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection mimicking Kawasaki disease has been described in Europe and the United States.5–9 The former does not usually include major respiratory involvement despite cases of severely ill children and adolescents have been reported. A specific analysis of the spectrum of COVID-19 respiratory disease in adolescents is lacking. We aimed to describe COVID-19 pneumonia prevalence and clinical characteristics in a pediatric referral center during the pandemics in Spain.

We evaluated adolescents (aged 10 to 18 years old) infected with SARS-CoV-2 from March 5 through June 30, 2020, in Hospital Sant Joan de Déu in Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain). During the lockdown in Spain (from March 16 until June 20, 2020), most pediatric departments in the region were shut and Hospital Sant Joan de Déu remained the largest pediatric referral center in Catalonia. Nasopharyngeal swabs were obtained for detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by molecular techniques (Genefinder COVID-19 Plus, Elitech; Puteaux, France). The local Ethics Committee approved the study (ref. PI-77-20) and a waiver for informed consent was granted.

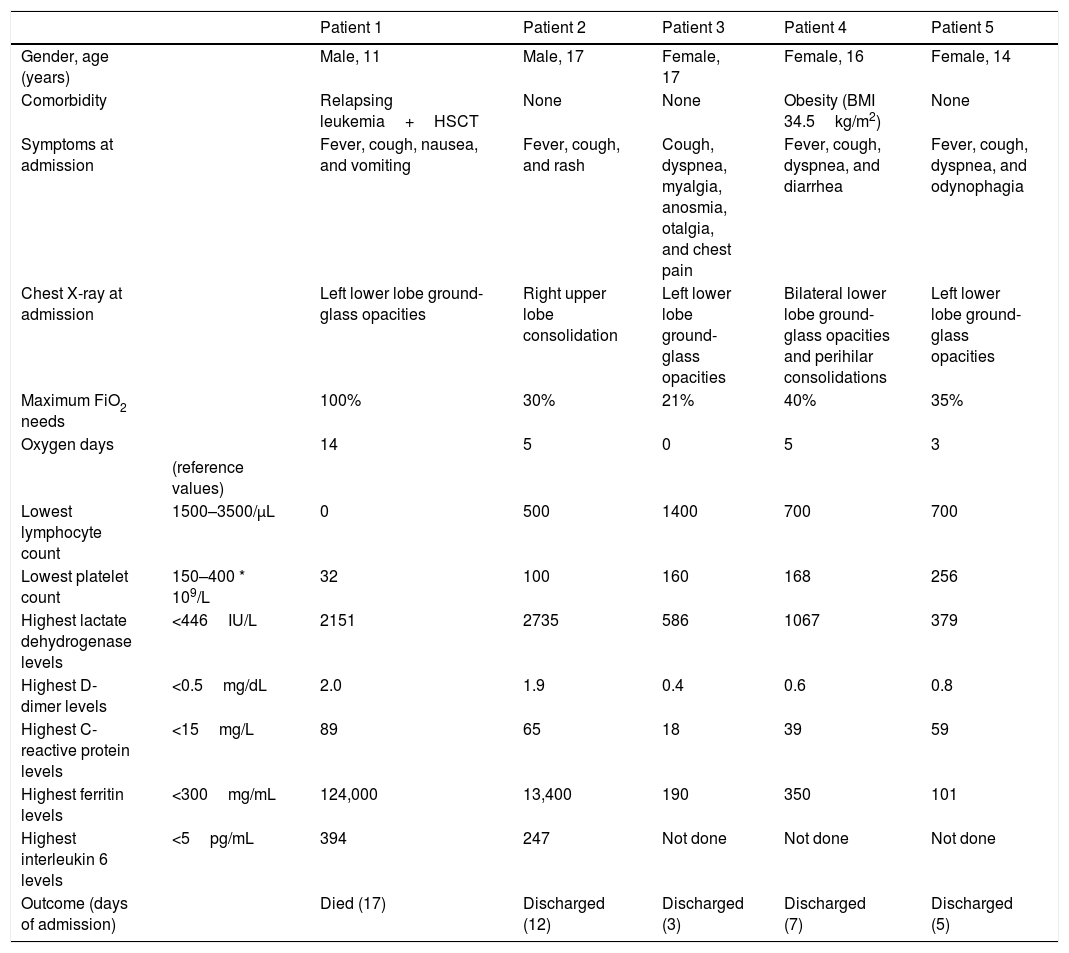

Overall, 58 adolescents (mean [SD] age: 13.2 [2.2] years) were confirmed to have SARS-CoV-2 infection during the study period. Overall, 16 patients were admitted: 5 adolescents (8.5%, Table 1) because of COVID-19 pneumonia, 3 patients (5.2%) due to SARS-CoV-2-related Kawasaki disease, and 8 patients (13.8%) because of non-COVID-19-related conditions (see Appendix 1, supplementary online content); other than respiratory symptoms, there were no clinical differences between patients with and without pneumonia at SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis (data not shown). Patients that did not require hospital admission (n=42) received only symptomatic treatment and were uneventfully followed-up on an outpatient basis.

Characteristics of 5 adolescents with COVID-19 pneumonia.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, age (years) | Male, 11 | Male, 17 | Female, 17 | Female, 16 | Female, 14 | |

| Comorbidity | Relapsing leukemia+HSCT | None | None | Obesity (BMI 34.5kg/m2) | None | |

| Symptoms at admission | Fever, cough, nausea, and vomiting | Fever, cough, and rash | Cough, dyspnea, myalgia, anosmia, otalgia, and chest pain | Fever, cough, dyspnea, and diarrhea | Fever, cough, dyspnea, and odynophagia | |

| Chest X-ray at admission | Left lower lobe ground-glass opacities | Right upper lobe consolidation | Left lower lobe ground-glass opacities | Bilateral lower lobe ground-glass opacities and perihilar consolidations | Left lower lobe ground-glass opacities | |

| Maximum FiO2 needs | 100% | 30% | 21% | 40% | 35% | |

| Oxygen days | 14 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3 | |

| (reference values) | ||||||

| Lowest lymphocyte count | 1500–3500/μL | 0 | 500 | 1400 | 700 | 700 |

| Lowest platelet count | 150–400 * 109/L | 32 | 100 | 160 | 168 | 256 |

| Highest lactate dehydrogenase levels | <446IU/L | 2151 | 2735 | 586 | 1067 | 379 |

| Highest D-dimer levels | <0.5mg/dL | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Highest C-reactive protein levels | <15mg/L | 89 | 65 | 18 | 39 | 59 |

| Highest ferritin levels | <300mg/mL | 124,000 | 13,400 | 190 | 350 | 101 |

| Highest interleukin 6 levels | <5pg/mL | 394 | 247 | Not done | Not done | Not done |

| Outcome (days of admission) | Died (17) | Discharged (12) | Discharged (3) | Discharged (7) | Discharged (5) |

Only 2 out of 5 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia had comorbid conditions (an 11-year-old boy with relapsing leukemia and a 16-year-old girl with obesity). All the patients showed lymphopenia and elevated inflammatory markers to some degree at or during admission. C-reactive protein, ferritin and d-dimer levels at admission significantly correlated with duration of admission and duration of respiratory support (Table 2, supplementary online content). All patients received oxygen therapy as needed, as well as oral azythromycin, oral hydroxycloroquine and intravenous ceftriaxone. The patient with relapsing leukemia and a 17-year-old healthy boy developed acute respiratory distress syndrome with elevated ferritin and IL-6, received tocilizumab and steroids as well (full clinical description can be found in Appendix 1, supplementary online content). Despite intensive care and further immunomodulatory treatment, the patient with leukemia developed multiorgan failure and died. The rest of the cases presented good recovery and were discharged after from 3 to 12 days of admission.

Our case series describes the spectrum of COVID-19 disease in adolescents, and reports almost a 10% prevalence rate of pneumonia in this age range. In a recent study including 48 SARS-CoV-2-infected children and adolescents admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit in the United States and Canada, most patients (73%) presented with respiratory symptoms, 83% had comorbidities and 56% were adolescents.10 One patient in our series died, he was an 11-year-old boy with relapsing leukeumia and several severe allogenic bone marrow transplant-associated complications. In the American case series, the two fatalities that were reported also occurred in adolescents (aged 12 and 17 years) with significant previous comorbidities.10

In the lack of evidence-based therapies for the management of COVID-19 at the time of admission, all patients in our series were treated according to local protocols that were adapted from national recommendations.11 They all received oral azythromycin, oral hydroxycloroquine and intravenous ceftriaxone. In spite of the latter, two patients in our series developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and were also treated with steroids and tocilizumab. A clinical trial has recently demonstrated that dexamethasone reduces 28-day mortality among COVID-19 patients that require respiratory support.12 The role of tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor, and other immunomodulatory agents in the attenuation of COVID-19-related cytokine release syndrome remains to be determined. In our center, positive previous experiences with tocilizumab in the treatment of cytokine release syndrome in children and young adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia receiving the anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy tisagenlecleucel prompted its early use in COVID-19 patients.13

Despite the referral bias and the likely underdiagnosis among asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic SARS-CoV-2-infected adolescents in Spain, our results suggest that COVID-19 more often presents with moderate to severe forms in adolescents than in younger children. Actually, 3 patients in our series had no previous comorbidities and they all presented with hypoxemic pneumonia and hyperinflammation syndromes similar to those described in adults.14 Nevertheless, our data confirm that the clinical course of COVID-19 pneumonia in adolescents is less severe and outcomes are better than in the adult population.

Interestingly, elevated inflammatory markers at admission (including C-reactive protein, d-dimer and ferritin) correlated with subrogate markers of severity such as duration of admission or duration of respiratory support. Bhumbra et al. recently reported similar results: in their case-study, lower leukocyte and platelet counts and higher C-reactive protein levels at admission were associated with admission in the pediatric intensive care unit.15 While these results are preliminary and should be confirmed in larger prospective studies, some of these parameters may prove useful in the early identification of adolescents at high risk of severe COVID-19 forms.

Conflicts of interest and source of fundingClàudia FORTUNY has received funds for speaking at symposia organized on behalf of Gilead Sciences. This work was supported by “Subvencions per a la Intensificació de Facultatius Especialistes” (Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, Programa PERIS 2016–2020) [SLT008/18/00193] to Antoni NOGUERA-JULIAN. The rest of authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.