Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) is a serious form of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection that can produce a wide range of clinical manifestations including septicemia, meningitis, arthritis, osteomyelitis, cellulitis, endocarditis,1 etc., which confers significant morbidity and mortality (especially in children under 2 years of age and in adults at risk due to medical conditions and/or advanced age). Incidence is variable, although in developed countries it is estimated to affect about 10 cases per 100000 individuals/year in the general population.2 We report the case of a patient with IPD who, after a non-consolidating acute respiratory infection, developed several thoracic and extrathoracic infectious complications.

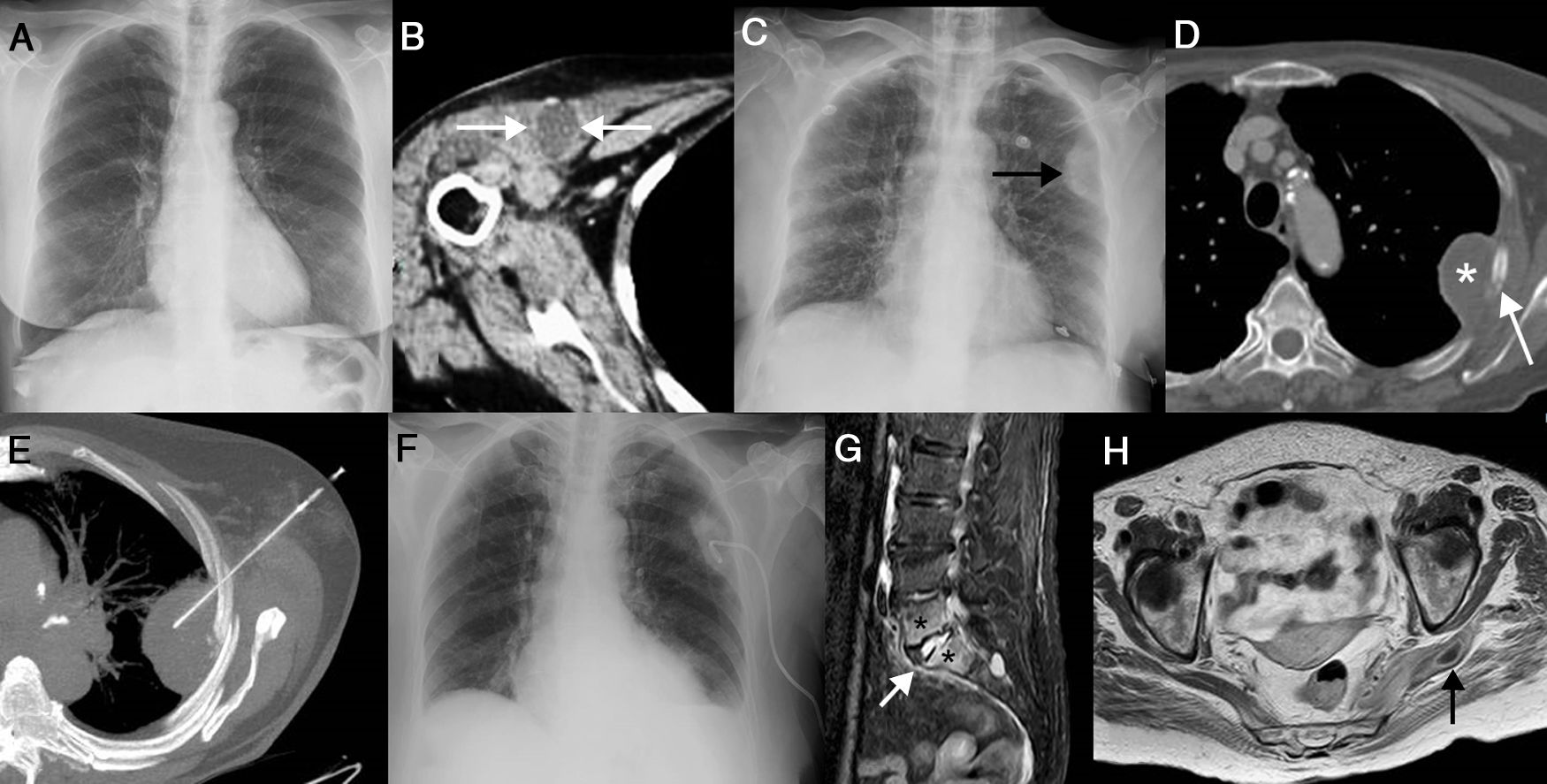

Our patient was a 67-year-old woman with no personal clinical history of interest, except smoking (pack-year index of 30) until 7 years previously. She consulted with a clinical picture of respiratory infection (without radiographic consolidation [Fig. 1A]). S. pneumoniae susceptible to multiple drugs was isolated from a blood culture kit. The patient, who was not vaccinated against pneumococcus, was initially treated with azithromycin, and showed rapid improvement in her respiratory symptoms. Within days of completing treatment, the patient developed low-grade fever and mixed mechanical and inflammatory pain in the right shoulder, which caused severe functional loss; physical examination showed right pre-pectoral erythema, increased ipsilateral shoulder volume, and intense pain in active and passive mobilization. Although an X-ray of the right shoulder showed no bone erosions, ultrasound and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the right shoulder confirmed joint effusion and the existence of periarticular collections (located in the pectoral musculature, Fig. 1B). Ultrasound-guided arthrocentesis demonstrated the presence of pus and encapsulated gram-positive cocci in the right glenohumeral joint (pneumococci were subsequently isolated in synovial fluid culture). Arthrotomy of the right shoulder and surgical cleaning of the periarticular collections were performed. A combined treatment of ceftriaxone and vancomycin was started, resulting in progressive improvement. Five days after joint drainage, the patient reported pleuritic-type pain in the left hemitorax. Chest X-ray showed the appearance of an extraparenchymal collection in the left hemitorax, initially interpreted as a pleural collection (Fig. 1C). A chest CT showed focal lysis of the left fourth costal arch surrounded by a collection. No parenchymal consolidations were identified (Fig. 1D). In view of these findings, interpreted as left costal osteomyelitis complicated by an extrapleural abscess, percutaneous drainage of this collection was performed with radiological control (Fig. 1E), obtaining purulent material (pneumococci confirmed on culture). Drainage continued for several days and several washings were performed with physiological serum, and a clinical and radiological improvement of this infectious focus was observed (Fig. 1F). Ten days after drainage, the patient experienced progressive and increased pain in the lumbar region radiating to the left gluteal and ipsilateral lower limb. A CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine confirmed signs of spondylodiscitis of the L5-S1 intervertebral space (Fig. 1G) and an abscess in the left pyramidal muscle (Fig. 1H), which were treated conservatively (continued parenteral antibiotic treatment). The patient was discharged a few days later and did not develop any infectious complications again, after maintaining antibiotic treatment for an additional 8 weeks.

(A) Posteroanterior chest X-ray showing no pneumonic consolidation. (B) Chest CT axial image showing a collection in the thickness of the right pectoralis major muscle (arrows). (C) Anteroposterior chest X-ray identifying a new extraparenchymal lesion. (D) Chest CT axial image showing a focal lytic lesion in the left fourth costal arch (arrow) surrounded by an extrapleural fluid collection (asterisk). (E) Chest CT axial image (maximum intensity projection) showing the percutaneous drainage procedure of the left hemithorax collection. (F) Follow-up anteroposterior chest X-ray showing radiological improvement of the collection. (G) MRI sagittal image (inversion-recovery sequence with fat suppression) identifying typical signs of acute spondylodiscitis: increased signal intensity in the L5-S1 intervertebral disc (arrow) and altered signal of the vertebral endplates adjacent to the disc (asterisks). (H) MRI axial image (T1-weighted sequence after intravenous gadolinium administration) showing a ring-enhancing collection in the thickness of the left pyramidal muscle (arrow).

Humans are the only known natural reservoirs of S. pneumoniae (pneumococcus). More than 30% of children and 5%–10% of adults are asymptomatic carriers of pneumococcus in their nasopharynx; however, this bacteria has a remarkable ability to spread to the airway (upper and lower) and invade the bloodstream or lymph vessels, causing a wide variety of infectious diseases.3 IPD represents the most serious form of pneumococcal infection, and can produce a wide range of clinical manifestations (from meningitis to endocarditis). This is a severe condition with significant morbidity and mortality (especially in children with hemoglobinopathies and immunosuppressed adults) and a variable incidence (10 cases per 100000 individuals/year in developed countries).1,2

Spontaneous osteomyelitis and septic arthritis (not occurring in patients surgically operated on a bone or joint) due to pneumococcus are very rare and particularly affect immunocompromised children, adolescents, or adults (especially patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and with asplenia/hyposplenism).4,5 Our patient did not have any predisposing factors that increased the risk of pneumococcal osteomyelitis and arthritis. Generally, the bone manifestations of pneumococcal osteomyelitis usually occur in patients with upper or lower respiratory tract infections (more or less clinically or radiologically evident), as in our patient. Symptoms are generally non-specific and include fever, chills, local pain, and increased soft tissue in the affected bone/joint.4 In our case, the patient developed several sequential joint and bone complications, despite the initial treatment of a non-consolidating respiratory infection, with low-grade fever and pain in different sites. Pneumococcal glenohumeral arthritis and spondylodiscitis are described in the literature, as is S. pneumoniae pyomyositis.6–8 Costal osteomyelitis is extremely rare (less than 1% of hematogenic osteomyelitis), and may be caused by: (1) penetrating trauma; (2) regional spread from a pneumonic empyema or focus; or (3) hematogeneous transmission. The most common causative microorganisms are Staphylococcus aureus and mycobacteria.9 To our knowledge, no similar cases of pneumococcal osteomyelitis in adults have been described in the literature. The only documented case of spontaneous pneumococcal costal osteomyelitis occurred in a 4-month-old infant, and eventually required partial resection of the rib after failed percutaneous fine-needle aspiration.10 The authors recommend surgical resection for the proper management of costal osteomyelitis. In our case, attention is drawn to the initial radiological presentation of this osteomyelitis in the form of an extraparenchymal collection, which suggested pleural empyema. A chest CT scan showed a focus of costal osteolysis surrounded by an extrapleural collection, differentiating it from pleural empyema. Percutaneous drainage was performed using a pigtail catheter with radiological control, achieving clinical and radiological improvement of this complication. Although the serotype was not investigated in this case, it is important to remember the importance of routinely investigating the different serotypes of S. pneumoniae isolates in invasive diseases for possible prevention.

We believe that early use of imaging tests for the diagnosis of infectious complications of IPD, as well as early surgical drainage of treatable infectious foci, are necessary, in addition to systemic antibiotic therapy, for optimal diagnostic and therapeutic management of these patients. We found no previously reported cases in the literature of adults with extrapleural collection associated with costal osteomyelitis in the context of an IPD, and we believe that early percutaneous drainage of this collection may contribute to the favorable control of the infection.

Please cite this article as: Gorospe Sarasúa L, Martín-Pinacho JJ, Ayala-Carbonero AM, Gambí-Pisonero E, Martín-Dávila P, Mirambeaux-Villalona RM, et al. Osteomielitis costal que simula un empiema pleural en una enfermedad neumocócica invasiva. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:535–537.