Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung neoplasm. Despite surgical resection, it has a high relapse rate, accounting for 30–55% of all cases. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) based on a customized gene panel and the analysis of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) can help identify heterogeneity, stratify high-risk patients, and guide treatment decisions. In this descriptive study involving a small prospective cohort, we focus on the phenotypic characterization of CTCs, particularly concerning EZH2 expression (a member of the Polycomb Repression Complex 2), as well as on the mutation profiles of the tissue using a customized gene panel and their association with poor outcomes in NSCLC.

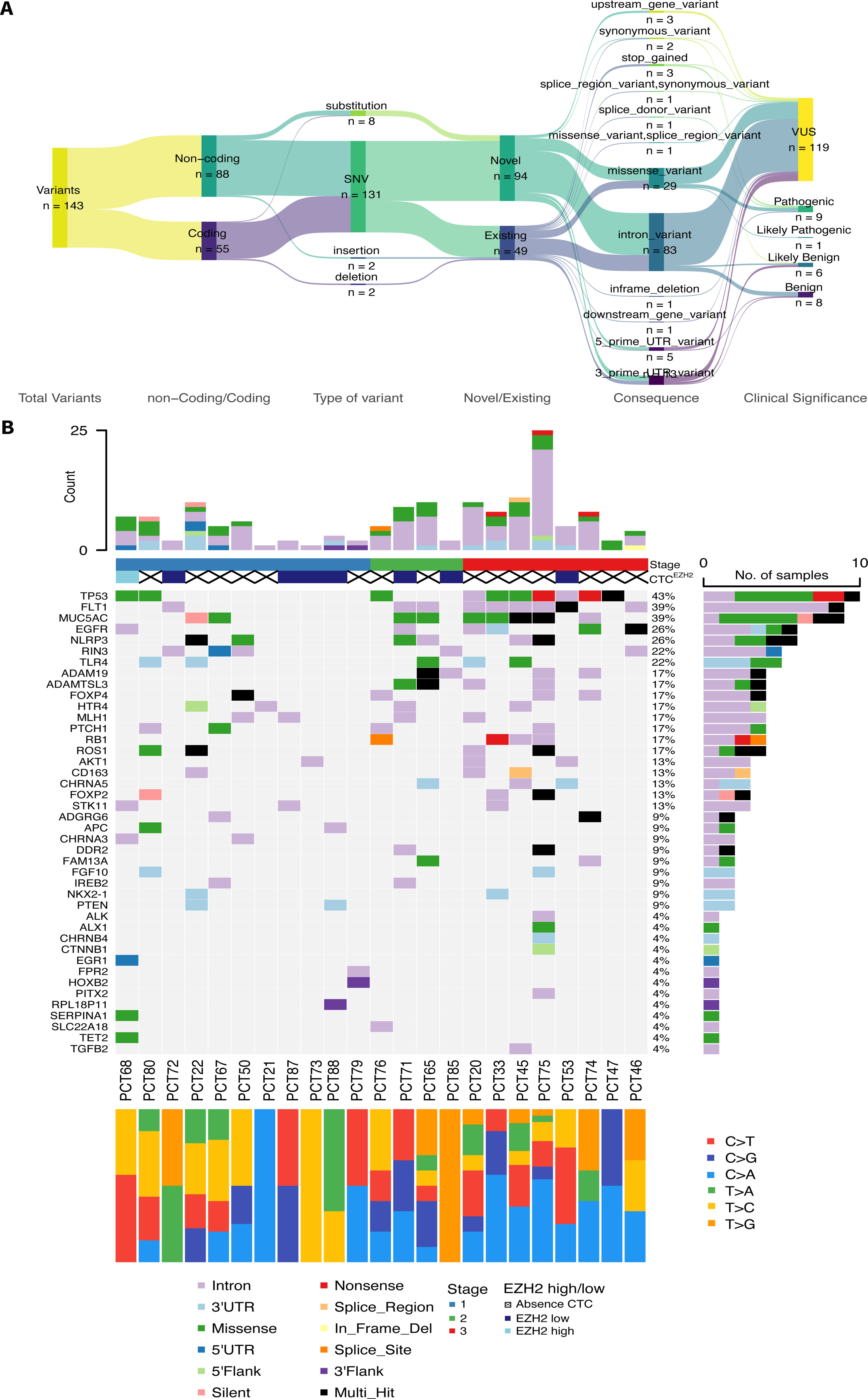

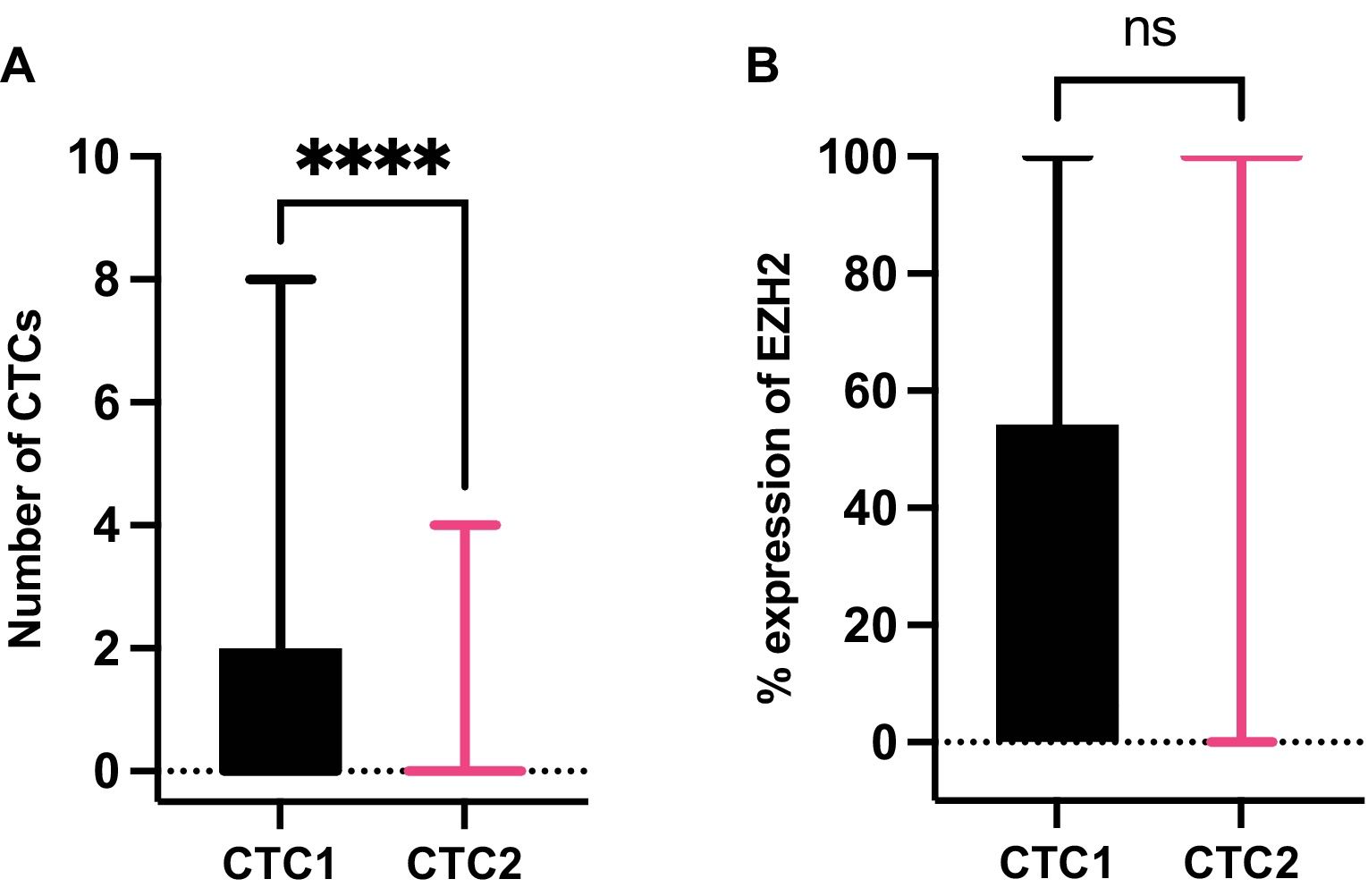

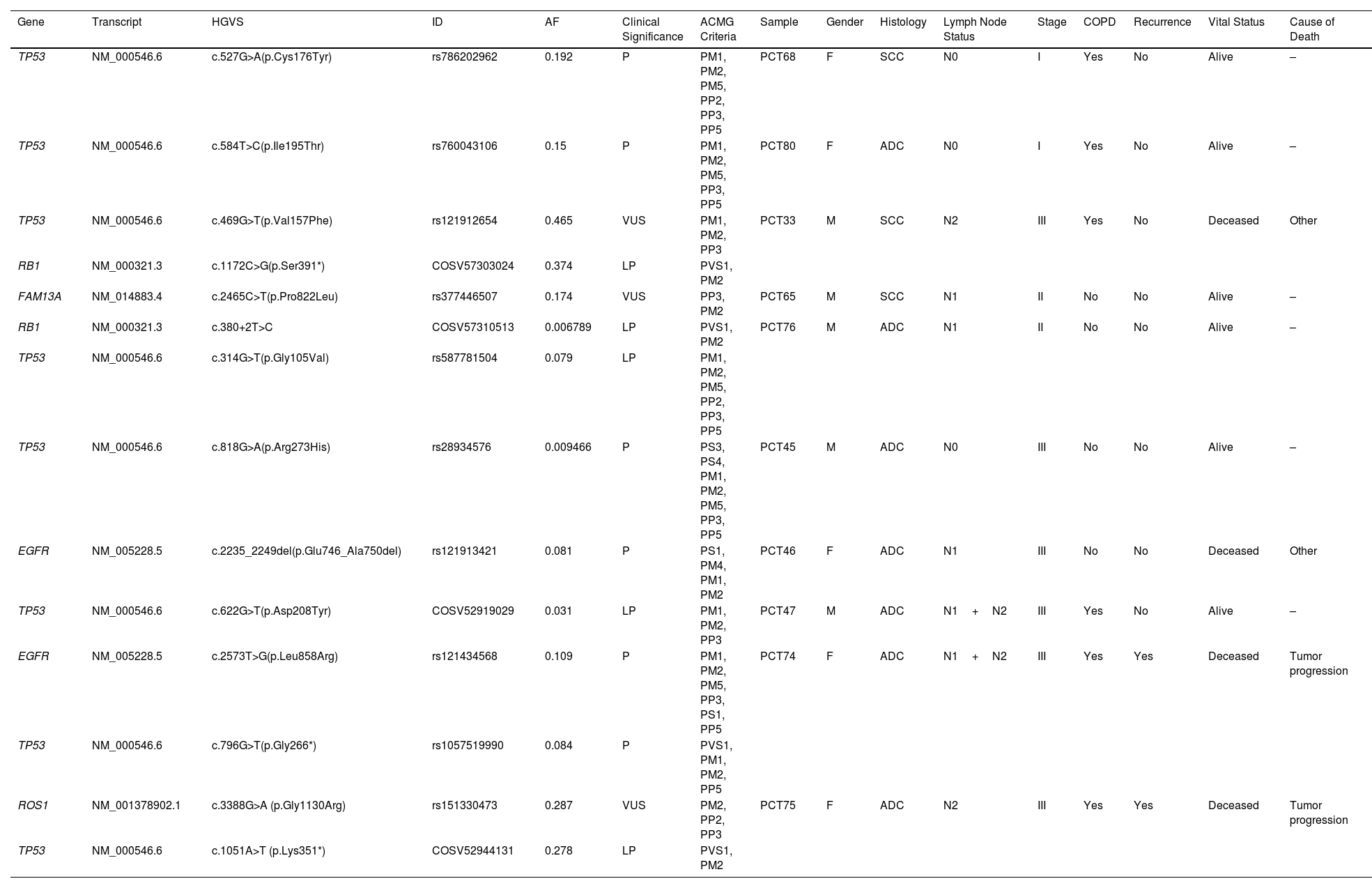

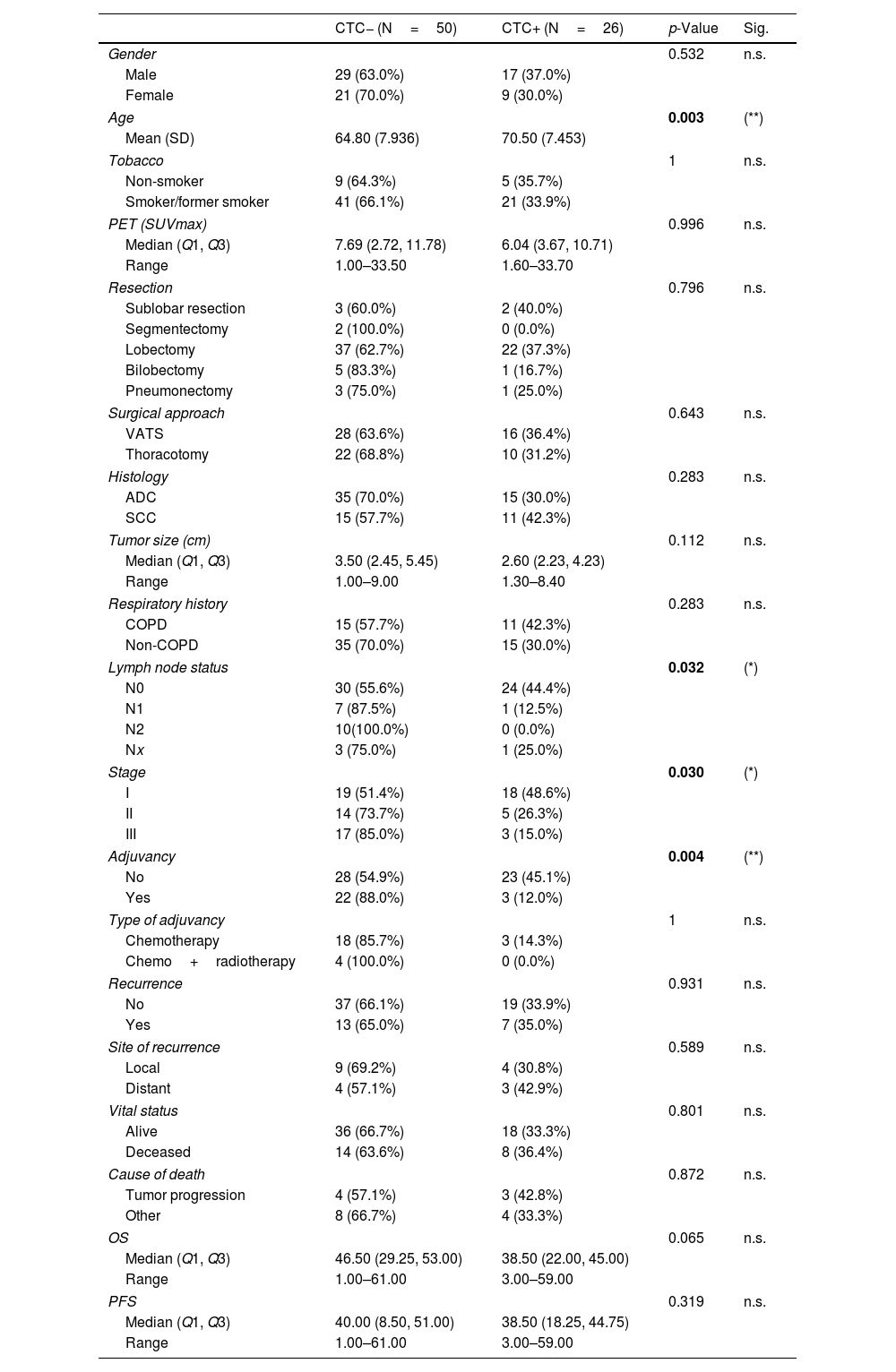

MethodsIsolation and characterization of EZH2 on CTCs were evaluated before surgical resection (CTC1) and one month after surgery (CTC2) in resectable NSCLC patients. Targeted NGS was performed using a customized 50-gene panel on tissue samples from a subset of patients.

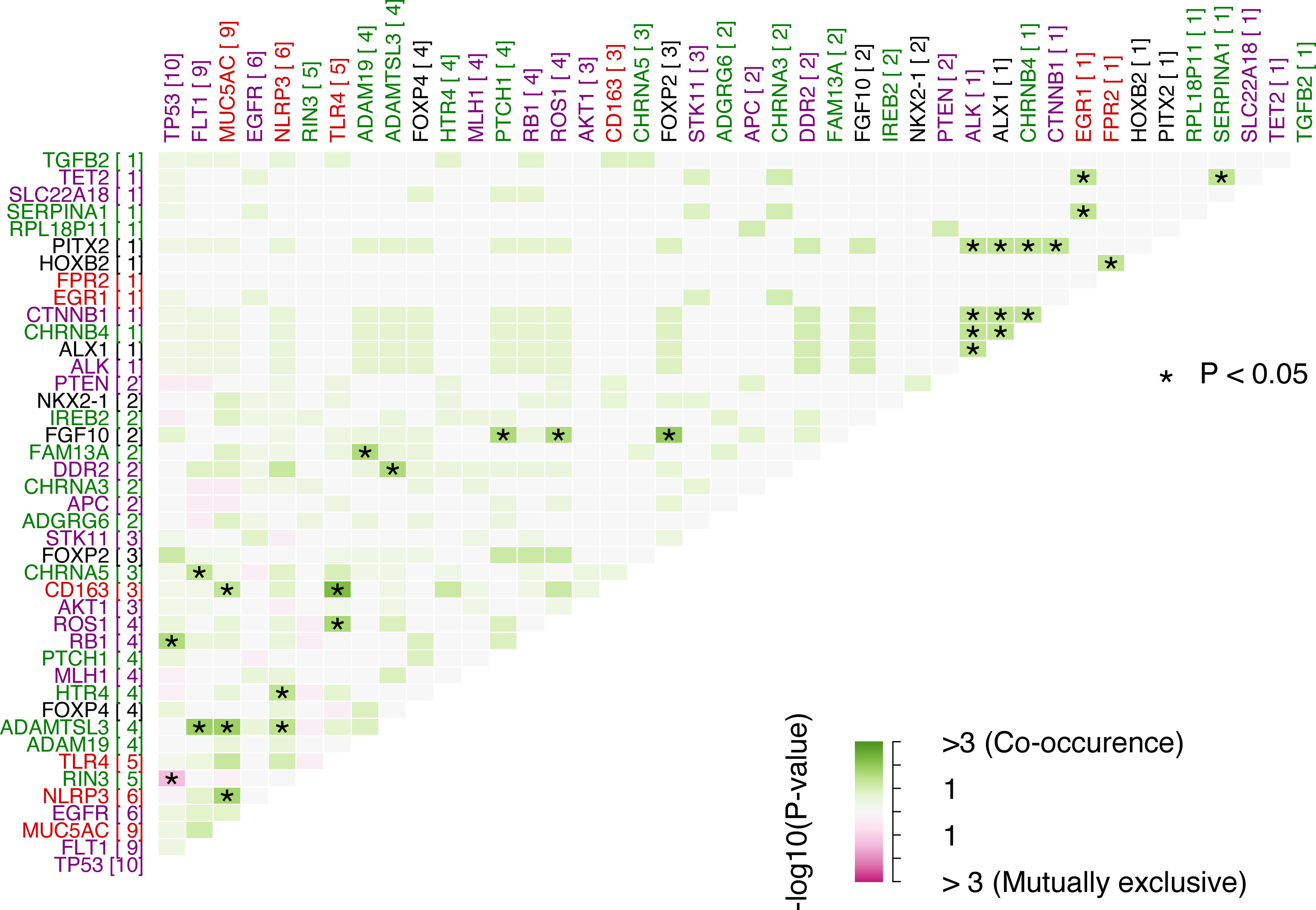

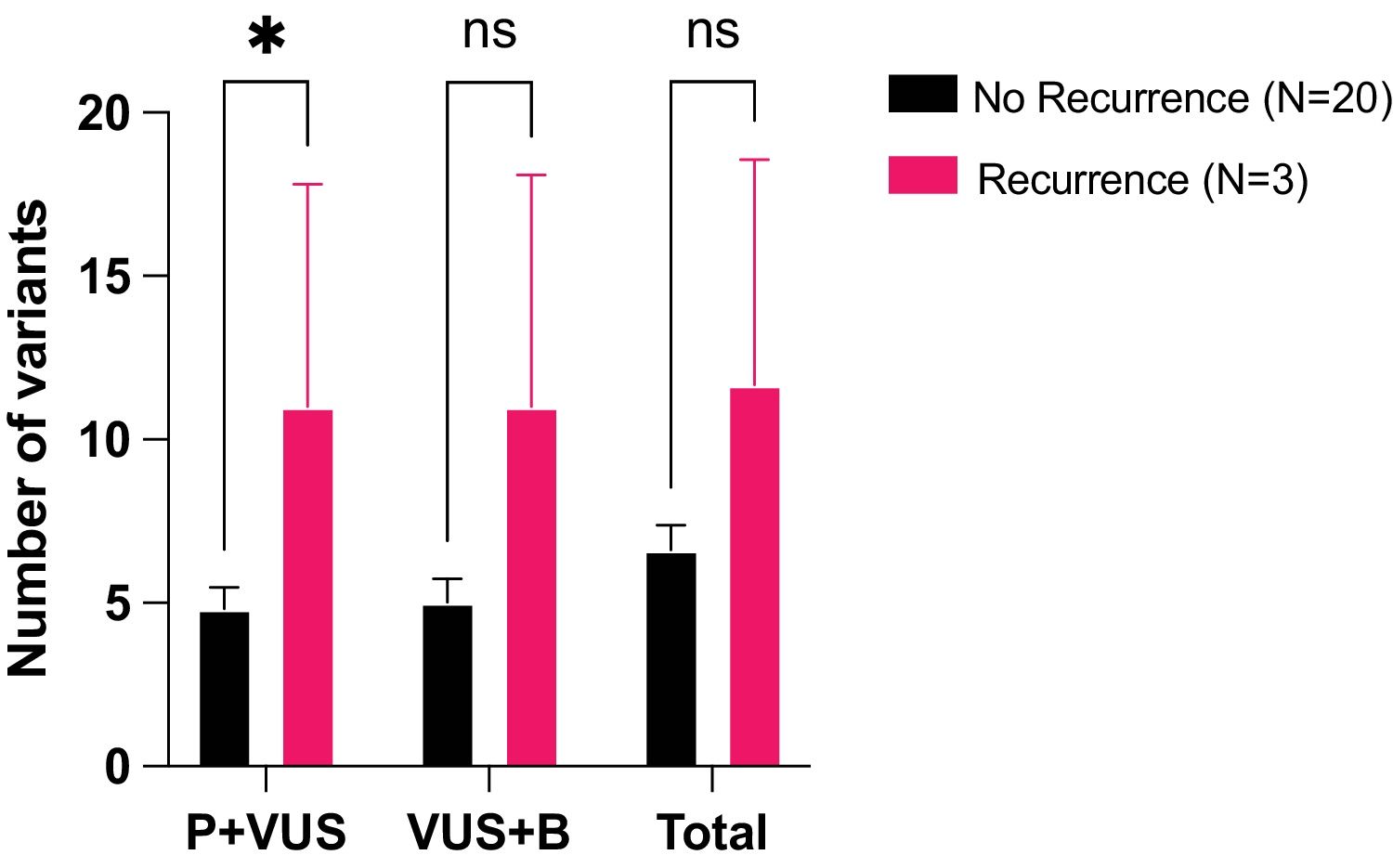

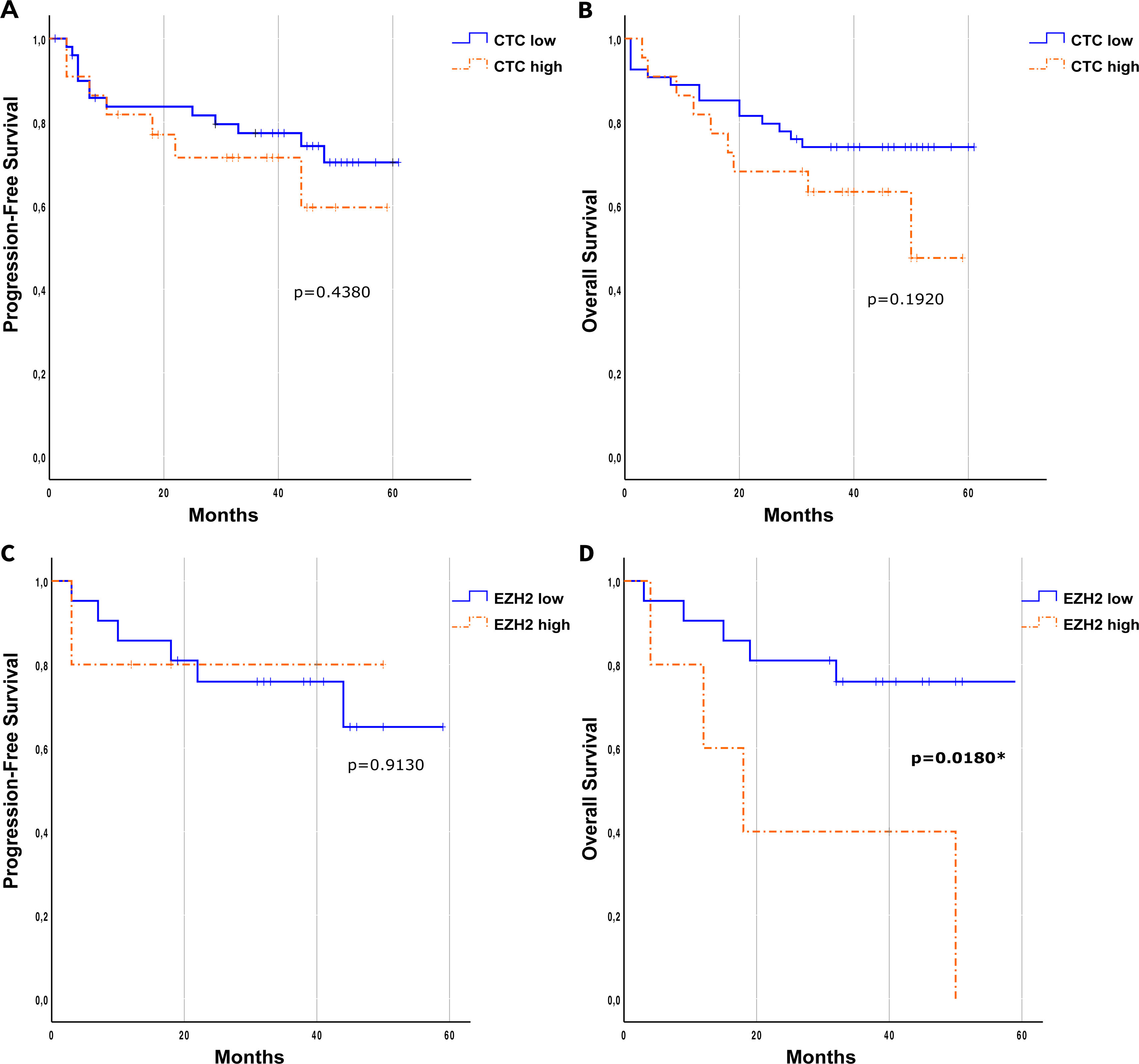

Results76 patients with resectable NSCLC were recruited. The top mutated genes in the cohort included TP53, FLT1, MUC5AC, EGFR, and NLRP3. Pair of genes that had mutually exclusive mutations was TP53-RIN3, and pairs of genes with co-occurring mutations were CD163-TLR4, FGF10-FOXP2, ADAMTSL3-FLT1, ADAMTSL3-MUC5AC and MUC5AC-NLRP3. CTCs decreased significantly between the two time points CTC1 and CTC2 (p<0.0001), and CTCs+ patients with high EZH2 expression had an 87% increased risk of death (p=0.018).

ConclusionsIntegrating molecular profiling of tumors and CTC characterization can provide valuable insights into tumor heterogeneity and improve patient stratification for resectable NSCLC.