Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is not considered a professional disease, and the effect of different occupations and working conditions on susceptibility to CAP is unknown. The aim of this study is to determine whether different jobs and certain working conditions are risk factors for CAP.

MethodologyOver a 1-year period, all radiologically confirmed cases of CAP (n=1336) and age- and sex-matched controls (n=1326) were enrolled in a population-based case–control study. A questionnaire on CAP risk factors, including work-related questions, was administered to all participants during an in-person interview.

ResultsThe bivariate analysis showed that office work is a protective factor against CAP, while building work, contact with dust and sudden changes of temperature in the workplace were risk factors for CAP. The occupational factor disappeared when the multivariate analysis was adjusted for working conditions. Contact with dust (previous month) and sudden changes of temperature (previous 3 months) were risk factors for CAP, irrespective of the number of years spent working in these conditions, suggesting reversibility.

ConclusionSome recent working conditions such as exposure to dust and sudden changes of temperature in the workplace are risk factors for CAP. Both factors are reversible and preventable.

La neumonía adquirida en la comunidad (NAC) no se considera una enfermedad profesional, por lo que se desconoce la influencia que puedan tener las distintas profesiones y condiciones laborales sobre el riesgo de desarrollar una NAC. El objetivo del estudio es conocer si las profesiones y determinadas condiciones laborales se pueden comportar como factores de riesgo de NAC.

MetodologíaEstudio de casos (n=1.336) y controles (n=1.326) de base poblacional. Se estudiaron todos los casos de NAC con confirmación radiológica, diagnosticados en una base poblacional, durante un año. Los factores de riesgo de NAC, incluyendo las profesiones y las condiciones laborales actuales, fueron estudiados mediante entrevista individual.

ResultadosEl análisis bivariado mostró que trabajar como administrativo es un factor protector de NAC, mientras que trabajar en la construcción, estar expuesto al polvo y sufrir cambios bruscos de temperatura en el trabajo son factores de riesgo de NAC. El efecto de las profesiones desaparece cuando se ajusta por las condiciones laborales en el análisis multivariado. El contacto con polvo (último mes) y cambios bruscos de temperatura recientes (últimos 3 meses) son factores de riesgo de NAC sin que ello guarde relación con el número de años trabajados en estas condiciones, lo que sugiere un carácter reversible.

ConclusiónAlgunas condiciones laborales recientes, como el contacto con polvo y cambios bruscos de temperatura, son factores de riesgo de NAC reversibles y potencialmente prevenibles.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) occurs at an incidence of between 1.6 and 13.5 cases/1000 inhabitants/year, depending on age. Hospitalization is necessary in 25–50% of cases, and the mortality rate is 3–24%; this has remained unchanged in recent years1 despite the use of preventive measures mortality.2 One of the best ways of limiting the impact of CAP is to act on modifiable risk factors.

Very few studies have analyzed professions and occupational exposure as risk factors for CAP. The possible impact of some types of occupational exposure on the respiratory system3 has been studied in the setting of specific diseases, such as bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiolitis, asthma, and lung cancer. However, we are unaware of any study that has investigated the effect of occupational exposure on the probability of developing CAP. The aim of this study was to determine whether certain jobs and working conditions constitute risk factors for CAP among the general adult population.

Materials and MethodsThe Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Catalan Countries (PACAP) study is a population-based case–control study of the risk factors for CAP in 849,033 inhabitants over the age of 14, registered in 64 primary care centers in a large rural and urban district in the east of Spain. The study methodology has been published elsewhere.4

Any lower respiratory tract infection requiring antibiotic treatment that presented with new or previously unknown focal signs on physical examination and chest X-ray was considered as clinical suspicion of CAP.5 All suspected CAPs were followed up with chest X-ray, according to clinical course, until complete resolution. Patients were excluded when suspected CAP was shown during monitoring to be another non-infectious respiratory disease. Patients diagnosed with active tuberculosis, suspected aspiration pneumonia, pneumonia acquired in residential care homes, and pneumonias with onset within 7 days of hospital discharge were also excluded. To ensure that all cases of CAP were identified, an active surveillance scheme was set up in primary care centers and hospitals, both public and private, in the study district, and in tertiary referral hospitals outside this area. The control group consisted of pairs matched for age (±5 years) and sex, selected randomly from the database of the primary care center that provided the cases.

Selected individuals completed a questionnaire on CAP risk factors in their home. If the patient could not respond directly due to mental illness, disease or death (in the case of a CAP patient), the questionnaire was completed by the caregiver or closest family member. The interviewers were doctors or nurses trained in interview techniques and the administration of the study questionnaire. Questions were divided into 3 sections: (a) habits and lifestyle; (b) chronic respiratory diseases and other clinical conditions; and (c) usual medication over the previous year. Information was collected on current job, contacts with presumably toxic substances (at any time in their working life or in the last month), including smoke, gases, vapors, dust, organic or inorganic fibers, and contact with animals. Sudden changes in temperature associated with work in the last 3 months were recorded, e.g., entering cold chambers or working in kitchens or furnaces (see Table 1). The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Consorci Sanitari del Maresme, and all selected subjects gave their informed consent to participate.

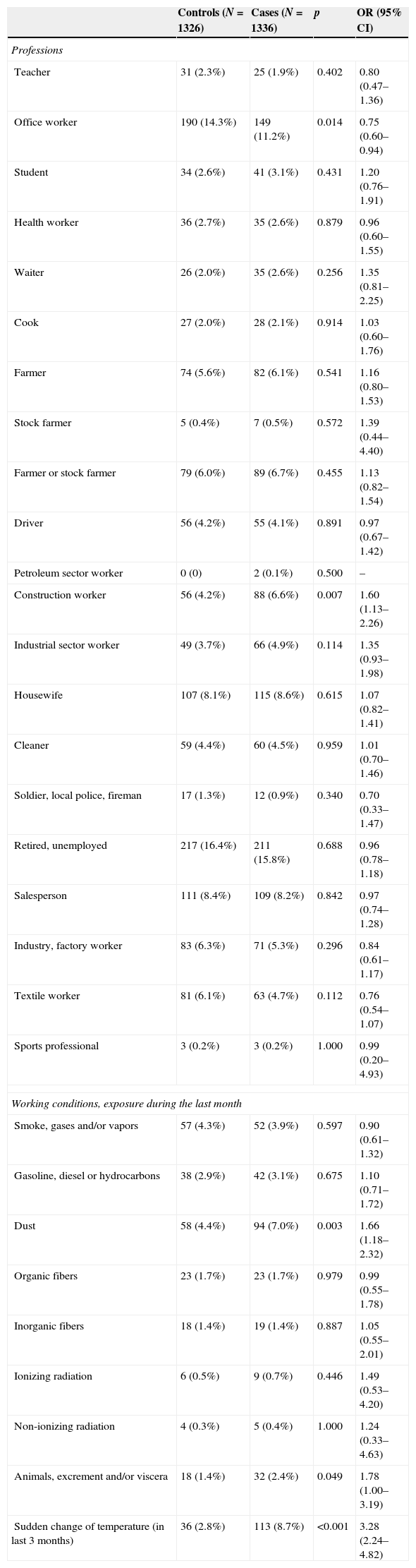

Risk of community-acquired pneumonia according to profession and current working conditions.

| Controls (N=1326) | Cases (N=1336) | p | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professions | ||||

| Teacher | 31 (2.3%) | 25 (1.9%) | 0.402 | 0.80 (0.47–1.36) |

| Office worker | 190 (14.3%) | 149 (11.2%) | 0.014 | 0.75 (0.60–0.94) |

| Student | 34 (2.6%) | 41 (3.1%) | 0.431 | 1.20 (0.76–1.91) |

| Health worker | 36 (2.7%) | 35 (2.6%) | 0.879 | 0.96 (0.60–1.55) |

| Waiter | 26 (2.0%) | 35 (2.6%) | 0.256 | 1.35 (0.81–2.25) |

| Cook | 27 (2.0%) | 28 (2.1%) | 0.914 | 1.03 (0.60–1.76) |

| Farmer | 74 (5.6%) | 82 (6.1%) | 0.541 | 1.16 (0.80–1.53) |

| Stock farmer | 5 (0.4%) | 7 (0.5%) | 0.572 | 1.39 (0.44–4.40) |

| Farmer or stock farmer | 79 (6.0%) | 89 (6.7%) | 0.455 | 1.13 (0.82–1.54) |

| Driver | 56 (4.2%) | 55 (4.1%) | 0.891 | 0.97 (0.67–1.42) |

| Petroleum sector worker | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1%) | 0.500 | – |

| Construction worker | 56 (4.2%) | 88 (6.6%) | 0.007 | 1.60 (1.13–2.26) |

| Industrial sector worker | 49 (3.7%) | 66 (4.9%) | 0.114 | 1.35 (0.93–1.98) |

| Housewife | 107 (8.1%) | 115 (8.6%) | 0.615 | 1.07 (0.82–1.41) |

| Cleaner | 59 (4.4%) | 60 (4.5%) | 0.959 | 1.01 (0.70–1.46) |

| Soldier, local police, fireman | 17 (1.3%) | 12 (0.9%) | 0.340 | 0.70 (0.33–1.47) |

| Retired, unemployed | 217 (16.4%) | 211 (15.8%) | 0.688 | 0.96 (0.78–1.18) |

| Salesperson | 111 (8.4%) | 109 (8.2%) | 0.842 | 0.97 (0.74–1.28) |

| Industry, factory worker | 83 (6.3%) | 71 (5.3%) | 0.296 | 0.84 (0.61–1.17) |

| Textile worker | 81 (6.1%) | 63 (4.7%) | 0.112 | 0.76 (0.54–1.07) |

| Sports professional | 3 (0.2%) | 3 (0.2%) | 1.000 | 0.99 (0.20–4.93) |

| Working conditions, exposure during the last month | ||||

| Smoke, gases and/or vapors | 57 (4.3%) | 52 (3.9%) | 0.597 | 0.90 (0.61–1.32) |

| Gasoline, diesel or hydrocarbons | 38 (2.9%) | 42 (3.1%) | 0.675 | 1.10 (0.71–1.72) |

| Dust | 58 (4.4%) | 94 (7.0%) | 0.003 | 1.66 (1.18–2.32) |

| Organic fibers | 23 (1.7%) | 23 (1.7%) | 0.979 | 0.99 (0.55–1.78) |

| Inorganic fibers | 18 (1.4%) | 19 (1.4%) | 0.887 | 1.05 (0.55–2.01) |

| Ionizing radiation | 6 (0.5%) | 9 (0.7%) | 0.446 | 1.49 (0.53–4.20) |

| Non-ionizing radiation | 4 (0.3%) | 5 (0.4%) | 1.000 | 1.24 (0.33–4.63) |

| Animals, excrement and/or viscera | 18 (1.4%) | 32 (2.4%) | 0.049 | 1.78 (1.00–3.19) |

| Sudden change of temperature (in last 3 months) | 36 (2.8%) | 113 (8.7%) | <0.001 | 3.28 (2.24–4.82) |

The distribution of profession and exposure to the various study factors were compared between cases and controls using the Chi-squared test (or Fisher's exact test, if appropriate). Mean years worked under the different conditions were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. To evaluate the effect of study factors on CAP, OR was estimated by logistical regression. A bivariate analysis and several multivariate models were conducted (one for each of the professions: office workers, construction, industry, teachers and farmers or stockmen) to adjust the effect of these professions for the effect of working conditions and other known CAP risk factors, such as asthma, chronic bronchial disease (including chronic bronchitis and COPD), and smoking habit. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsA total of 1336 confirmed cases of CAP and 1326 controls were included. In total, 52.7% of the CAP cases were men, with a mean age±standard deviation of 58.6±19.8 years; 47.3% were women, with a mean age of 54.6±20.7 years. Table 1 shows the distribution of professions and working conditions between cases and controls. Office work is clearly a protective factor against CAP (OR=0.75), while working in construction is a risk factor (OR=1.60). No statistically significant association was found for any of the other professions studied. With regard to working conditions, a significant effect was found for contact with dust in the previous month (OR=1.66), or contact with animals, excrement or viscera, also during the previous month (OR=1.78), or exposure to sudden changes in temperature in the last 3 months (OR=3.28). In contrast, no statistically significant effect was found when number of years working under these conditions was related with development of CAP.

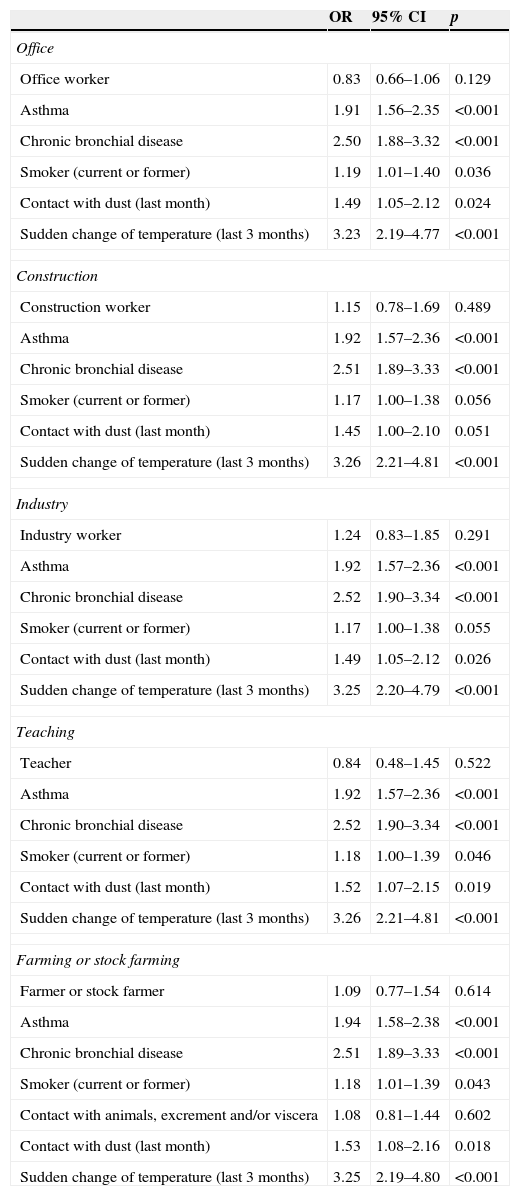

Results of the multivariate models show that the occupational effect disappears after adjustment for working conditions, smoking habit, and chronic respiratory disease (Table 2). The effect of contact with dust and sudden changes of temperature, meanwhile, remains constant in all models, with a very stable OR, close to 1.5 in the first case and 3.25 in the second.

Effect of professions related to working conditions and other known community-acquired pneumonia risk factors.

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Office | |||

| Office worker | 0.83 | 0.66–1.06 | 0.129 |

| Asthma | 1.91 | 1.56–2.35 | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchial disease | 2.50 | 1.88–3.32 | <0.001 |

| Smoker (current or former) | 1.19 | 1.01–1.40 | 0.036 |

| Contact with dust (last month) | 1.49 | 1.05–2.12 | 0.024 |

| Sudden change of temperature (last 3 months) | 3.23 | 2.19–4.77 | <0.001 |

| Construction | |||

| Construction worker | 1.15 | 0.78–1.69 | 0.489 |

| Asthma | 1.92 | 1.57–2.36 | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchial disease | 2.51 | 1.89–3.33 | <0.001 |

| Smoker (current or former) | 1.17 | 1.00–1.38 | 0.056 |

| Contact with dust (last month) | 1.45 | 1.00–2.10 | 0.051 |

| Sudden change of temperature (last 3 months) | 3.26 | 2.21–4.81 | <0.001 |

| Industry | |||

| Industry worker | 1.24 | 0.83–1.85 | 0.291 |

| Asthma | 1.92 | 1.57–2.36 | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchial disease | 2.52 | 1.90–3.34 | <0.001 |

| Smoker (current or former) | 1.17 | 1.00–1.38 | 0.055 |

| Contact with dust (last month) | 1.49 | 1.05–2.12 | 0.026 |

| Sudden change of temperature (last 3 months) | 3.25 | 2.20–4.79 | <0.001 |

| Teaching | |||

| Teacher | 0.84 | 0.48–1.45 | 0.522 |

| Asthma | 1.92 | 1.57–2.36 | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchial disease | 2.52 | 1.90–3.34 | <0.001 |

| Smoker (current or former) | 1.18 | 1.00–1.39 | 0.046 |

| Contact with dust (last month) | 1.52 | 1.07–2.15 | 0.019 |

| Sudden change of temperature (last 3 months) | 3.26 | 2.21–4.81 | <0.001 |

| Farming or stock farming | |||

| Farmer or stock farmer | 1.09 | 0.77–1.54 | 0.614 |

| Asthma | 1.94 | 1.58–2.38 | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchial disease | 2.51 | 1.89–3.33 | <0.001 |

| Smoker (current or former) | 1.18 | 1.01–1.39 | 0.043 |

| Contact with animals, excrement and/or viscera | 1.08 | 0.81–1.44 | 0.602 |

| Contact with dust (last month) | 1.53 | 1.08–2.16 | 0.018 |

| Sudden change of temperature (last 3 months) | 3.25 | 2.19–4.80 | <0.001 |

The results of this study show that while an individual's profession is not independently related with the development of CAP, some recent working conditions are. This is surprising in some cases – teachers, for example, are not at increased risk, despite spending time in close contact with children, while cohabitation with children at home is a risk factor for CAP.4,6 It is also interesting to note that the risk of pneumonia is not higher in healthcare professionals, despite their greater exposure to possible contacts.

Recent exposure to dust and sudden changes of temperature were identified as independent risk factors for CAP, so preventive measures should be implemented in some workplaces to avoid these situations. Exposure to certain particles, such as soot, silica crystals, cotton dust, and cadmium, may increase susceptibility to COPD,7 known to be one of the main risk factors of CAP. Nevertheless, it is unclear if dust from these and other substances has a direct, independent effect on the development of pneumonia.

Neupane et al.8 explored this issue in a population study designed to investigate the effect of environmental pollution. They found that CAP was more prevalent in patients older than 65 years who had been exposed in the workplace to gases, smokes and fumes (particularly from metal), or chemicals during their working life. Nevertheless, the authors themselves recognize9 that as patient-reported parameters did not form part of the main study objective they were not correctly validated, and warn that data should be interpreted with caution. In a case–control study in patients over 65 years of age, Loeb et al.10 reported that previous occupational exposure to gas, smoke or chemicals constituted an independent risk factor for CAP and an increased risk of hospitalization for this disease.11 In a systematic review of articles on CAP risk factors published before 2003, Kohlhammer et al.12 found that the only statistically significant occupational factor was exposure to metal fumes13 and occupational contact with dust.14 Even so, the interpretation of the results of Farr et al.14 is limited by their inclusion of only CAP patients requiring hospitalization. Moreover, the only factors included in the multivariate model were cohabitation with domestic animals, contact with children or use of gas heaters – other known risk factors were not taken into consideration. The same authors also separately analyzed patients with less severe CAP who did not require hospital admission. In this group, while the univariate analysis shows statistical significance for occupational exposure to dust, this significance disappears in the multivariate analysis. Coggon et al.15 reported the results of an observational, retrospective study conducted among welders in Southampton (United Kingdom). They identified a greater risk of mortality due to CAP in welders aged 15–64 years, but not in those aged over 65, leading them to conclude that welding fumes could increase susceptibility to CAP, but that this effect was reversible. The same group subsequently designed a multicenter study in 11 English hospitals that included patients aged 20–64 years admitted for CAP; controls were patients admitted over the study period for reasons other than respiratory disease. Patients completed a questionnaire on their usual working conditions and exposure to metal fumes, and other non-occupational factors. The only significant finding with OR=1.6 (1.1–2.4) was recent exposure (within 1 week before onset of symptoms) to metal fumes (iron),13 suggesting that welding fumes, particularly from iron, is a predisposing but reversible factor for CAP. These results support our findings that CAP is associated with contact with dust in the last month, but not affected by the number of years working in those conditions.

Fewer data are available on the relation between CAP and sudden changes of temperature. Hippocrates, in his scientific observations 2500 years ago, described how sudden changes in temperature could affect public health.16 Lower environmental temperatures have been proven to increase the incidence and severity of respiratory infections.17,18 This has been associated with changes in natural or acquired immunity,19,20 and local effects of cold air on the bronchial tree have been associated with bronchoconstriction or pharyngeal tissue damage.21,22

The main limitations of our study include possible errors in patient reporting of exposure, possible memory bias in collecting data on occupational conditions and exposures, and the difficulty of classifying jobs into a reasonable number of categories.

To conclude, although an individual's profession as such is not related with a greater risk of CAP, some working conditions, such as contact with dust and recent sudden changes in temperature, are reversible, modifiable risk factors, and are therefore of interest in occupational prevention of CAP.

FundingGrant 08/PI 090448 of the Healthcare Research Fund (FIS) and CIBER for Respiratory Health (06/06/0028).

Authors’ ContributionMethodological design: Mateu Serra-Prat, Ignasi Bolíbar, Jordi Almirall. Field work: Jordi Almirall, Ramon Boixeda, Maria Bartolomé, Jordi Roig, Mari C. de la Torre, Olga Parra. Data analysis and interpretation: Elisabet Palomera, Mateu Serra-Prat, Ignasi Bolíbar, Jordi Roig, Jordi Almirall. Manuscript preparationo: Jordi Almirall, Mateu Serra-Prat, Mari C. de la Torre, Olga Parra, Ramon Boixeda, Maria Bartolomé, Antoni Torres.

Conflict of InterestsNone.

Our thanks to all the GEMPAC group members (Maresme Community-Acquired Pneumonia Study Group).

Please cite this article as: Almirall J, Serra-Prat M, Bolíbar I, Palomera E, Roig J, Boixeda R, et al. Relación de las profesiones y las condiciones laborales con la neumonía adquirida en la comunidad. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:627–631.