Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare genetic condition resulting from the malfunction of motile cilia in several organs. Poor mucociliary clearance in the lungs results in a vicious vortex of transmural infections, inflammation, obstruction and damage of the airways which will eventually result in bronchiectasis.1

Recent evidence from genomic medicine has demonstrated that PCD is more common as a cause of bronchiectasis than was previously considered. Advances have been made in identifying the clinical presentation, in the diagnostic process, as well as in therapeutic approaches. This article will elaborate on the newest research in these fields and future challenges.

PCD is more common than previously considered: PCD was previously reported to have a prevalence ∼1:16,0002 based on rates of situs inversus in a Norwegian population. Modern gene sequencing reveals a doubling in the estimated prevalence and PCD to affect at least 1:7500 people. This figure is based on the analyses of the allele-frequency for 29 PCD-causing genes in several large genomic databases.2 This is likely to remain an underestimate given that to date over 50 genes are known to cause PCD. This suggests the majority of sufferers remain undiagnosed. In the UK in adults with bronchiectasis a diagnosis of PCD by whole genome sequencing was revealed in 12% of patients who were previously thought to have severe idiopathic bronchiectasis while in an audit of ∼5000 bronchiectasis patients<2% had been tested.5 suggesting an increased need to identify and test patients for PCD in idiopathic bronchiectasis cohorts. Diagnosis of a cause of bronchiectasis is important to patients and health care professionals. Not only does an underlying diagnosis have an impact on the clinical care of patients, prompting multidisciplinary care and access to treatments and services, but it also has a large psychological impact to know about the cause of one's disease.1

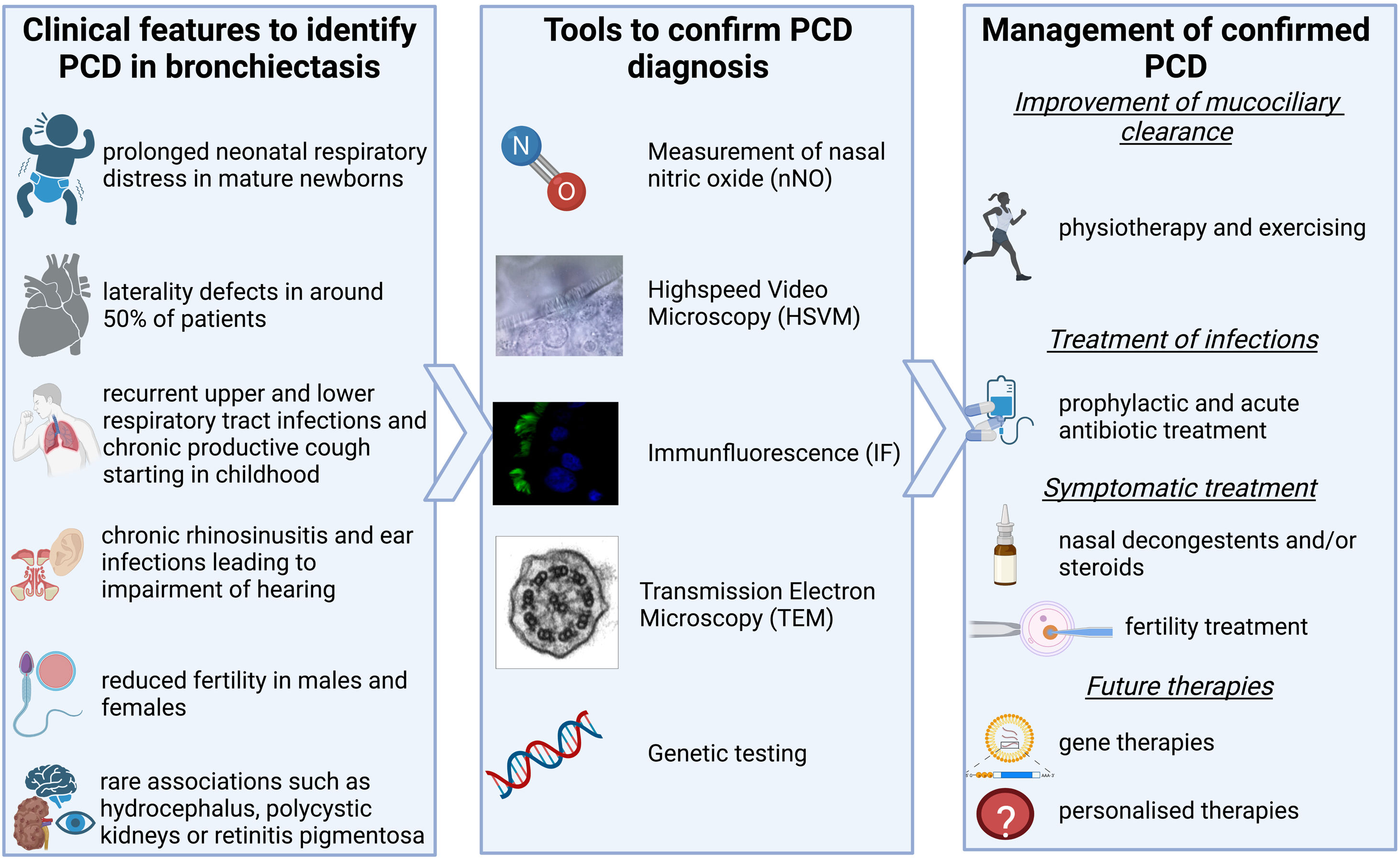

How do we identify patients with PCD? PCD can present with a variety of symptoms as shown in Fig. 1. Lung disease from a young age, including chronic infection & inflammation leading to bronchiectasis, is the predominant presentation; but most patients also experience chronic rhinosinusitis and recurrent otitis media starting at a young age which can lead to impairment of hearing.1 Around 50% of patients have laterality defects, such as situs inversus totalis, heterotaxia, or situs ambiguous, due to the malfunctioning of the embryonic nodal cilia which plays a vital role in the normal rotation of the thoraco-abdominal organs.1 Reduced fertility can also be related to PCD with the cilia lining the epithelia of the fallopian tube and the ultrastructure of the sperms flagella being similar to that of cilia.6,9,10 New data on subfertility show that the transport of sperm in the efferent duct which is lined with motile cilia might be affected also. Such studies remind us to also consider the non-respiratory symptoms of PCD when identifying patients.7 Increasingly genotype-phenotype relationships are revealed. Some genotypes are not associated with infertility (CCDC114), or situs defects (RSPH4A, RSPH1, RSPH9, DRC2). Certain genotypes are associated with milder disease (e.g. DNAH11 and CCDC103H154P) while others can be more severe (e.g. CCNO, CCDC39 and CCDC40).8 These examples come from an increased understanding of the genetic heterogeneity of the condition, with >50 known genes and >2000 known mutations PCD is increasingly described as a collection of motile ciliopathy disorders rather than a single disease. Most inheritance is autosomal-recessive but recently new genes have been described to be disease-causing when inherited x-linked (e.g. PIH1D3) or autosomal-dominant (e.g. FOXJ1). The known genes cause around 70% of identified PCD cases,1 a rate that will be improved by the discovery of new genes and better sequencing techniques in the future. Nonetheless for now, diagnostics cannot entirely depend on genetic testing alone.3,4

How do we diagnose PCD? Once an individual with possible PCD is identified there are two guidelines on how to diagnose PCD – one from the European Respiratory Society (ERS)3 and one from the American Thoracic Society (ATS).4 Both include the five main diagnostic tests that are shown in Fig. 1.4,5 Confirmation of a diagnosis remains through identification of pathogenic variants in a known gene or a hallmark defect of ciliary ultrastructure by electron microcopy. In both guidelines, low levels of nasal NO (nNO) plays an important role. It has previously been estimated to have a sensitivity and specificity of over 90% in several studies.1 However, newer studies have shown that nNO is higher in patients with specific mutations. Raidt J et al. and Legendre M et al. both showed that nNO can be over the widely used cut-off of 77nl/min in patients with PCD, normal nasal NO is often associated with normal ultrastructure in TEM or mutations leading to dyskinetic but motile cilia.9,10 These studies should be considered when a patient presents with a likely history of PCD but normal nNO.

How is the management of a patient with confirmed PCD? Treatment is mainly symptomatic focusing on improvement of mucociliary clearance and early treatment of airway infections as well as symptomatic treatment of rhinosinusitis, otitis media, cardiac complications and subfertility.11

The first ever multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial conducted in patients with PCD was to test maintenance therapy with the macrolide antibiotic Azithromycin. This antibiotic not only acts bacteriostatically, but also has an anti-inflammatory component, inhibits quorum sensing, and was previously shown to have a positive effect in patients with bronchiectasis.12 The ‘BESTCILIA’ trial showed that the use of Azithromycin could halve the rate of respiratory exacerbations and the number of bacteria in the sputum in patients with PCD.13 A focus of ongoing research is to find more personalised treatments. A phase 2 trial has been conducted to test the DPP-1 inhibitor Brensocatib in patients with bronchiectasis. DPP-1 is an enzyme that plays an active role in the activation of neutrophil serine proteases. With the inhibition of DPP-1, Brensocatib was able to reduce the exacerbation rate by 40% in comparison to a placebo group.14 A phase 3 trial including patients with PCD is currently ongoing (NCT04594369).

Genetic therapies are currently being developed in vitro and focus either on the replacement or on the repair of the mutated sequence.11 Advances in mRNA replacement therapy present an opportunity for PCD therapy and several commercial companies have programmes of work in this area. As an example, correction of the DNAI1 defect was recently able to increase ciliary beat frequency in a mouse model.15 Future challenges will be to recruit sufficient number of accurately diagnosed patients into trials to test therapies.

What have we learned from this? PCD as a cause of bronchiectasis has a higher prevalence than previously thought.2,5 The main focus in clinic is often the lung disease, but recent research has brought more attention to non-respiratory symptoms.7 Furthermore the diagnostic process will need to be adapted to the ongoing research: high nNO levels in patients with normal ultrastructure in TEM show that nNO might be less sensitive than previously thought, whereas the detection of new causative genetic variants will make genetic testing even more important.1,9,10 The treatment of PCD and bronchiectasis is exclusively symptomatic but with new studies for personalised and disease specific treatment, this will hopefully change in the future making treatment more effective.13,15

ContributionConception, writing and approval of this manuscript (all authors).

Conflict of interestAS has received speakers fees from Insmed, Consulting fees from Spirovant and grants from AstraZeneca, CP and DC have nothing to disclose.

Authors are members of the EMBARC and BEAT-PCD European Respiratory society Clinical Research Collaborations.