Rheumatic polymyalgia (RPM) is a relatively common inflammatory disease of unknown origin that presents almost exclusively in adults over the age of 50. It is characterized by morning pain and stiffness in the cervical region and in the pectoral and pelvic girdles and may be associated with giant cell arteritis (GCA).1 Pleural or pericardial effusion is rare in patients with RPM without GCA and is exceptional as a manifestation of disease onset.2

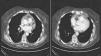

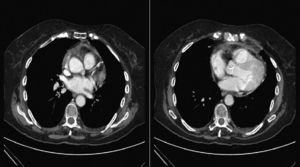

The case of a 76-year-old woman who presented in the emergency room with fever (38°C) is reported. She had had episodes of fever and pain in the pectoral girdle radiating to the cervical region over the previous 2 months. On one occasion, she had received oral corticosteroids in tapering schedule, with improvement. Physical examination revealed a systolic murmur in the aortic region and absent breath sounds in the base of the left lung. Clinical laboratory tests showed C-reactive protein 25.5mg/dl and a small left pleural effusion was observed on the chest X-ray. The initial diagnosis was pneumonia with parapneumonic pleural effusion and the patient was hospitalized with empiric antibiotic therapy. Despite this, her fever persisted and further examinations were performed. The immunological study revealed positive antinuclear antibodies in a speckled pattern. Tumor marker analysis showed elevated CA-125 levels. The chest-abdominal computed tomography showed a small left pleural effusion and minimal pericardial effusion (Fig. 1). After consultation with the rheumatologist, a diagnosis of RPM with serosal involvement was made and treatment with prednisone (starting dose: 15mg/day) was initiated. Subsequent clinical course was favorable with resolution of fever and pleural effusion. Three months after discharge the patient remained asymptomatic, so the corticosteroid doses were progressively reduced until discontinuation. The patient has since remained asymptomatic, with no new outbreaks of RPM over a 2-year follow-up period.

Although the elevated CA-125 antigen levels detected in this study may have been caused by other processes, such as Meigs pseudosyndrome secondary to struma ovarii, it was finally interpreted as indicative of serosal involvement. In a review of the literature, only 5 cases of RPM with associated pericardial effusion were identified, of which three also presented pleural effusion. Thoracocentesis was performed in one of these cases. The resulting fluid was borderline transudate/exudate, and cytology was negative for malignancy. In another case, pericardiectomy with pericardial biopsy was performed. Analysis of the pericardial fluid showed proteins 5.2g/dl, lactate dehydrogenase 4562IU/l and glucose 65mg/dl. Histological examination found inflammation with fibrosis and areas of interstitial bleeding with fibrin deposits, and the immunohistochemical analysis revealed lymphocytic infiltrate with predominance of T-cells.3

In conclusion, RPM should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients over 50 years of age with pleural and/or pericardial effusion.4,5 It is essential to identify the cause of effusion in patients with RPM due to the spectacular response to corticoid treatment.

Please cite this article as: Jarana Aparicio I, Pedraza Serrano F, de Miguel Díez J. Derrame pleural y pericárdico en una paciente con polimialgia reumática. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:370–371.