Surfactant protein C deficiency causes interstitial lung disease (ILD) of varying severity. Diagnosis in children is complex, due to the rarity and heterogeneous clinical manifestations of this entity.1,2 We report a case of this disease that was initially incorrectly diagnosed.

Our patient was a boy, born at term, with no significant history. At the age of 14–15 months, he was admitted twice due to bronchiolitis caused by syncytial respiratory virus and bronchitis due to adenovirus. After the second admission, persistent tachypnea, respiratory failure, and bilateral infiltrates on chest X-ray were observed. Further examinations ruled out malformations, immunodeficiencies, pulmonary hypertension, and other infections. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed: cell count was normal, with no eosinophilia, and negative Gram stain and microbiological cultures. Lung computed tomography (CT) showed a diffuse ground glass pattern with hilar lymphadenopathies. Lung biopsy was performed by thoracoscopy. The specimen was sent to a reference laboratory, and the report described “changes associated with bronchiolitis obliterans”. The patient was discharged at the age of 16 months with a diagnosis of post-infective bronchiolitis obliterans.

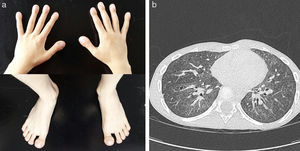

His initial clinical progress appeared to be consistent with this diagnosis. He required home oxygen therapy until the age of 24 months, and presented repeated respiratory exacerbations due to viral infections with multiple admissions, but progressive improvement was observed, with asymptomatic intervals between episodes. At the age of 6 years, despite maintaining daytime and nighttime saturations, the boy presented progressive dyspnea on minimal effort, poor weight gain, a dystrophic appearance, and digital clubbing of the hands and feet (Fig. 1a), basal forced spirometry with restrictive pattern (FVC 0.49L [43%], FEVI 0.48 [51%], FEV1/FVC ratio of 89%), and pathological walk test results (initial SaO2: 95%; final SaO2: 89% and 402m walked). This led us to reconsider the initial diagnosis, and the chest CT was repeated, revealing progression of the ground glass pattern and multiple new intraparenchymal cystic lesions (Fig. 1b).

The lung biopsy obtained when the patient was an infant was sent to the same laboratory for reassessment. The report this time described “chronic pneumonitis with incipient fibrosis, changes in lung development, hypoalveolization with septal muscularization and interstitial glycogenosis”. In view of the patient's progress and CT findings, surfactant protein deficiency ILD was suspected. A genetic study was performed, in which a heterozygous I73T mutation in the SFTPC gene was detected, leading finally to a diagnosis of surfactant protein C deficiency. Treatment began with oral hydroxychloroquine (6.5mg/kg/day), continuing 10 months later, with mild clinical improvement.

When a disease does not progress according to the usual clinical course, the initial diagnosis must be reconsidered, new evaluations should be performed, and ILD must be included in the differential diagnosis.3 Diseases that can cause ILD share similar clinical, radiological, and histological characteristics, but their etiology varies widely. ILDs caused by surfactant protein C deficiency are rare and heterogeneous, and require a high level of suspicion for correct diagnosis.1,2

Lung surfactant is a mixture of lipids and proteins produced by type II pneumocytes. It contains 6 main proteins: A, B, C, D, ABCA3 and NKX2; C is a hydrophobic protein, which is essential for surfactant function. Protein B and ABCA3 deficiencies are serious diseases that begin in the neonatal period, although the latter may develop at later stages, with a less severe course. Protein C deficiency is an autosomal dominant entity, most commonly associated with an I73T mutation in the SFTPC1 gene. It can occur at any age and progress is usually more insidious.1,2

More than 50 mutations have been described, with no clear relationship between genotype and phenotype,2 and although the pathophysiology of protein C deficiency ILD is unknown, one proposal is that it may be due to intracellular accumulation of the cytotoxic proprotein C.2 No specific treatment is available for protein C deficiency, but hydroxychloroquine has been reported as effective, alone or in combination with corticosteroids,2,4 as its anti-inflammatory properties are associated with the inhibition of intracellular accumulation of proprotein C.4

The diagnosis of ILD is still difficult, particularly in the pediatric age group. Clinical, radiological, and histological findings across the various entities may be very similar. Clinical suspicion and the genetic study of surfactant proteins are important diagnostic tools.2,5

Please cite this article as: Moreno-Galarraga L, Díaz Munilla L, Herranz Aguirre M, Navarro Jimenez A, Moreno Galdó A. La enfermedad pulmonar intersticial en el niño. Todavía hoy un reto diagnóstico. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:169–171.