Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide among both men and women, accounting for 1.6 million deaths annually. In Chile, it is the second leading cause of death due to cancer.1,2 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 85% of lung cancers; unfortunately, up to 80% of cases are diagnosed in advanced stages, requiring systemic therapy.3 In recent decades, significant advances have been made in the treatment of these patients, with the development of therapies aimed at specific mutations of the tumor cells (targeted therapies) and more recently with immunotherapy.

Among the most widely used immunotherapies are monoclonal antibodies against PD-1 or PD-L1. Their action is based on the ability of some tumors to evade the immune system through the expression of PD-L1, a ligand for a protein called PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1). When PD-1 and PD-L1 bind, T cell activation is inhibited, thus blocking the normal immune response to tumor cells. Some of these therapies are already approved for the treatment of lung cancer, and show longer survival rates than those obtained with conventional chemotherapy.4

One of the most important challenges in the use of PD-L1 inhibitors is correct patient selection. One of the most commonly used markers is PD-L1 expression in tumor cells, which is evaluated using immunohistochemical techniques. Pembrolizumab is an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of NSCLC. First-line therapy with pembrolizumab requires that at least 50% of the tumor cells express PD-L1, and for second-line therapy, at least 1%.5

The studies that led to the approval of anti-PD-L1 therapies were all conducted using large tissue samples from either excisional biopsies or core biopsies.5–7 Such samples are not always available in NSCLC patients, since diagnosis is often made with smaller samples obtained with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA). This is a minimally invasive technique that has been recommended by many scientific societies as the diagnostic procedure of choice in central airway lesions or those which require mediastinal staging.8,9 The usefulness of this type of biopsy for measuring PD-L1 expression is unclear, and may differ in terms of diagnostic accuracy, fundamentally because of the number of tumor cells in these samples. We report here on the feasibility of determining PD-L1 expression in NSCLC samples obtained by EBUS-TBNA.

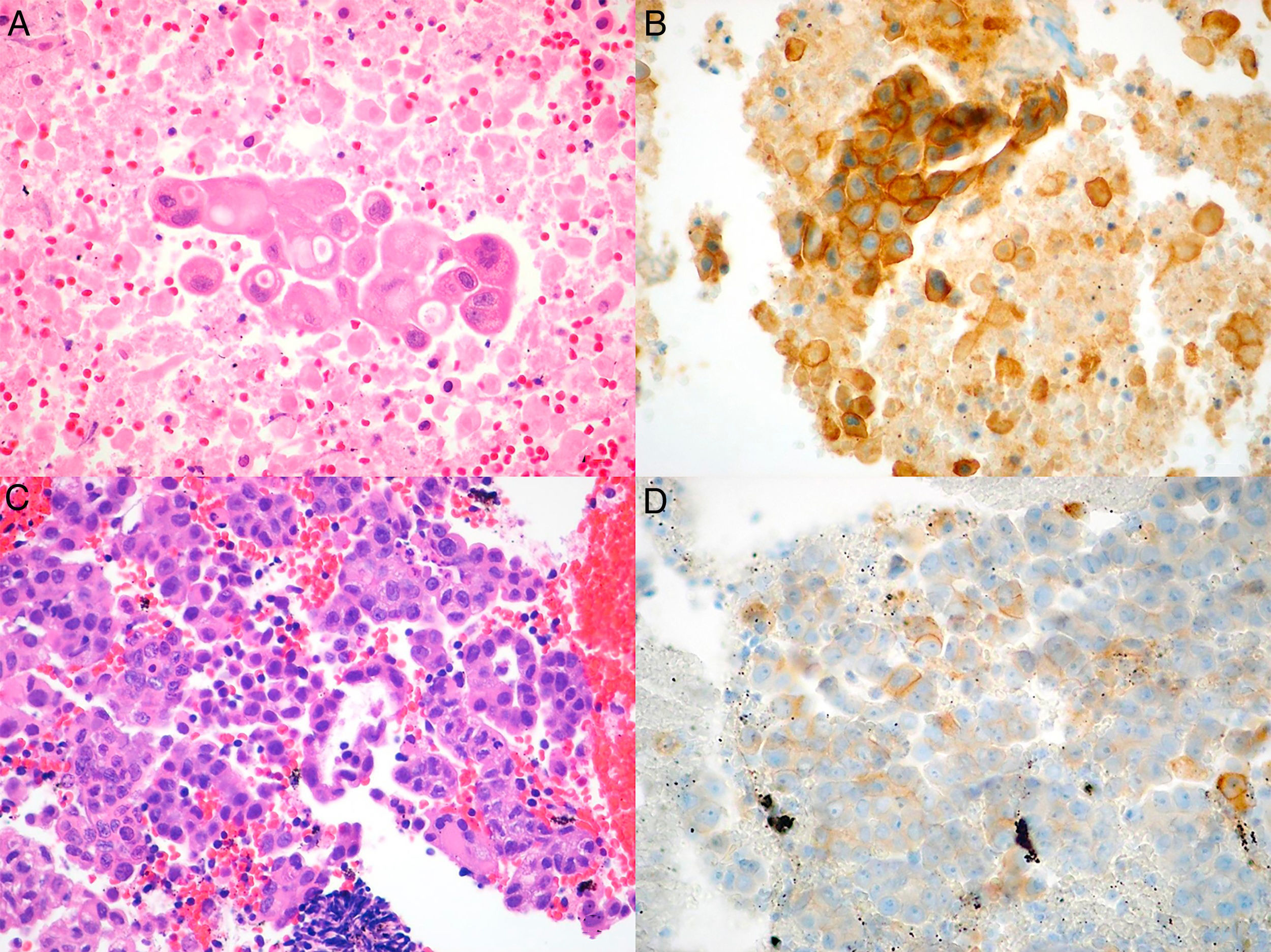

We conducted a retrospective review of all NSCLC cases in whom PD-L1 studies were requested. The cases were identified from the pathology laboratory database, and we included all patients seen between July 1, 2015, when this technique was first available in our hospital, and June 1, 2017. The study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution. Histopathological diagnosis and PD-L1 expression analysis were performed by an expert pathologist specializing in lung diseases. Samples were considered adequate for PD-L1 staining if they contained more than 100 evaluable cancer cells. The samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, buffered, and embedded in paraffin; 4μm tissue slices were cut and stained with hematoxylin–eosin, and incubated with anti-PD-L1monoclonal antibody (E1L3N®) XP® Rabbit mAb in the Ventana Benchmark ULTRA automated system (Roche), according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. PD-L1 expression was evaluated with a manual count of the percentage of cancer cells with membrane staining, whether partial or complete, and irrespective of intensity (Fig. 1A–D).

Microscopic images of the tumor samples obtained by EBUS-TBNA and of the respective immunohistochemical stains with anti-PD-L1 E1L3N antibody. (A) Adenocarcinoma (hematoxylin–eosin, 40×). (B) Membrane staining of >50% of cancer cells (PD-L1 E1L3N XP Rabbit mAb, 40×). (C) Adenocarcinoma (hematoxylin–eosin, 40×). (D) Membrane staining of >1% of cancer cells (PD-L1 E1L3N XP Rabbit mAb, 40×).

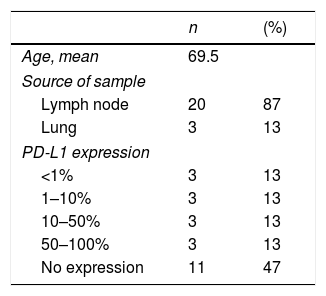

All samples from the total 23 requests for PD-L1 determination were adequate for the procedure. Of these 23 cases, 18 were adenocarcinomas, 3 squamous cell carcinoma, 1 adenosquamous, and 1 unspecified non-small cell carcinoma.

Mean age was 70 years (range 41–88), and most patients (12/23, 52%) were women. The samples were lymph node aspirates in 20/23 patients (87%), and the others were from lesions adjacent to the central airway.

Among the 23 cases analyzed, we found 3 (13.04%) samples with PD-L1 staining in >50% of the cancer cells, 6 (26.08%) with staining in 1%–50%, and 14 (60.86%) with staining in <1%. Of the 14 cases with staining in <1%, 11 showed no staining. The results of anti-PD-L1 immunohistochemical staining in cancer cells are shown in Table 1.

This study suggests that, similarly to their use in the determination of the most common mutations,10 in a high percentage of cases, EBUS-TBNA samples are adequate for evaluating PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Only 13% of samples were positive, defined as staining of more than 50% of the cancer cells (95% CI: 0.028–0.336), while the vast majority of cases were negative for PD-L1 expression. When 1% was used as a cut-off point, positivity rose to 26% (95% CI: 0.10–0.48).

Very few studies have evaluated PD-L1 expression in samples obtained by EBUS-TBNA.11,12 Larger biopsy samples yield PD-L1 positivity of around 50% with a cohort cut-off point >50%.7,13 Although these figures appear to be higher than those observed in our group, this may be a chance occurrence, due to the limited number of cases in our series (reflected by the wide confidence interval). If the number of PD-L1-positive samples really is lower than reported in the literature, this may be associated with ethnic differences among our population, and also with differences in the techniques used, for example, due to tumor heterogeneity.

This is the first study in South America to evaluate the feasibility of measuring PD-L1 in EBUS-TBNA samples. Unfortunately, it has the limitations associated with a small number of patients, and a population recruited from the same hospital. It should be noted that while it is possible to measure PD-L1 in samples obtained by EBUS, we cannot determine if the positivity observed in samples obtained by needle aspiration is representative of positivity in the primary tumor, and, more importantly, if these samples are useful for predicting response to therapy. These questions must be answered in further studies.

Please cite this article as: Fernandez-Bussy S, Pires Y, Labarca G, Vial MR. Expresión de PD-L1 en muestras de cáncer pulmonar no microcítico obtenidas por EBUS-TBNA. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:290–292.