Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major public health problem. In 2013, 9 million new cases of active TB were estimated globally and the proportion of reported new cases with multi-drug resistance (MDR) was 3.5%.

MethodsContact tracing of a case of pulmonary tuberculosis was performed in a Bolivian patient. Diagnostic tests were performed according to national and local protocols.

ResultsAn outbreak of tuberculosis in an immigrant community was detected, with 5 cases originating from one index case. Genotyping and drug susceptibility testing of the sputum samples determined Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistant to isoniazid (KatG-msp unmutated/inhA 5 RBS CT). Active case finding revealed a total of 39 contacts with an incidence of latent infection of 71.43%.

ConclusionsThe present study confirms the importance of active case finding through contact tracing as well as rapid laboratory diagnosis to achieve improvements in early detection of TB. Early diagnosis of the patient, compliance with appropriate treatment protocols and monitoring of drug resistance are considered essential for the prevention and control of TB.

La tuberculosis (TB) continúa siendo un importante problema de salud pública. En 2013 se declararon 9 millones de casos nuevos de TB activa a nivel mundial, siendo la proporción de nuevos casos de TB multirresistente del 3,5%.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio de contactos de un caso de TB pulmonar en una paciente de nacionalidad boliviana. Las pruebas diagnósticas se realizaron según los protocolos establecidos a nivel nacional y local.

ResultadosSe detectaron 5 casos a partir del caso índice y se constató la existencia de un brote de TB en una comunidad inmigrante. El resultado del genotipado y del antibiograma ampliado de las muestras de esputo fue crecimiento de Mycobacterium tuberculosis (KatG-msp no mutado/inhA C-T 5 RBS) resistente a isoniacida. Se realizó la búsqueda activa de convivientes y contactos con un censo total de 39 personas. La incidencia de infección latente fue de 71,43%.

DiscusiónEl estudio de este brote como otros en la literatura constata la importancia de la búsqueda activa de la localización de contactos y su estudio, de la investigación de laboratorio para lograr la mejora en la detección precoz de la TB. Un diagnóstico precoz del enfermo, el cumplimiento de un tratamiento adecuado y la vigilancia de la farmacorresistencia se consideran pilares fundamentales para la prevención y el control de la TB.

Tuberculosis (TB) was once one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in Spain, and it continues to be a serious worldwide health problem. It is a transmissible, notifiable disease, caused by bacteria from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) complex, and can affect any organ, although the most common presentation is pulmonary. It is most often transmitted from person to person by airborne mechanisms. The main risk factor for developing the disease among infected individuals is human immunodeficiency virus infection or autoimmune deficiency syndrome, but other risk factors have been reported, including diabetes, silicosis, immunosuppressive treatments, chronic renal disease, and malignant disease.

Worldwide, national and regional alliances, which have mobilized to create specific programs for the control of TB, have played a decisive role in the fight against the disease.1 In 2012, 8.6 million new cases of active TB were reported globally, of which 450000 were multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). In 2013, the incidence of TB rose to 9 million affected individuals, of which 3.5% were new cases of MDR-TB; these figures have remained stable in recent years.1

In the last 6 years in Spain, TB rates have remained above the average for the European Union, despite the downward trend perceived in the analysis of the latest published data. In 2013, the rate was 11.88 cases per 100000 inhabitants. This figure is 8.3% lower than in 2012, when 12.95 cases/100000 were reported, and in 2011, when 14.74 cases/100000 inhabitants were reported.2

The percentage of cases of TB detected in Spain but originating in another country was 31.2% in 2012 and 15.97% in 2013, mainly in the 24–34 year age group. Cases originating in Spain were mainly distributed among the over-65s, and the 35–44 years age group.3

In Castile and Leon, 288 cases of TB were registered in 2013, representing a rate of 11.43 cases per 100000 inhabitants (17% fewer cases than in 2012). Of these, 22 cases were associated with an outbreak (7.64%). The most common risk factor was immigrant status (7.76% of cases).4

An outbreak is defined as 1 or more of cases of TB occurring after the first case is detected.5 Several factors can boost an outbreak, such as exposure, and delay in obtaining a sputum smear and diagnosis, among others.6–9 In 2013, 61 outbreaks of pulmonary TB were reported to the National Epidemiological Surveillance Network. This number is lower than in previous years (135 in 2011 and 92 in 2012), although the figures may be underestimated due to delays in reporting.4

Tuberculous disease can only be controlled with the implementation of a program based on early diagnosis of the patient, compliance with the right treatment, follow-up of cases to ensure cure, and instigation of specific contact tracing.10

Drug-resistance testing is essential in the control of TB, particularly in the context of an outbreak.10

Material and MethodsThis study was initiated after the index case was reported to the Department of Preventive Health and Public Health of the Hospital Clínico Universitario of Valladolid. The protocol for tracing, treatment, and follow-up of cohabitants and contacts for TB was implemented.

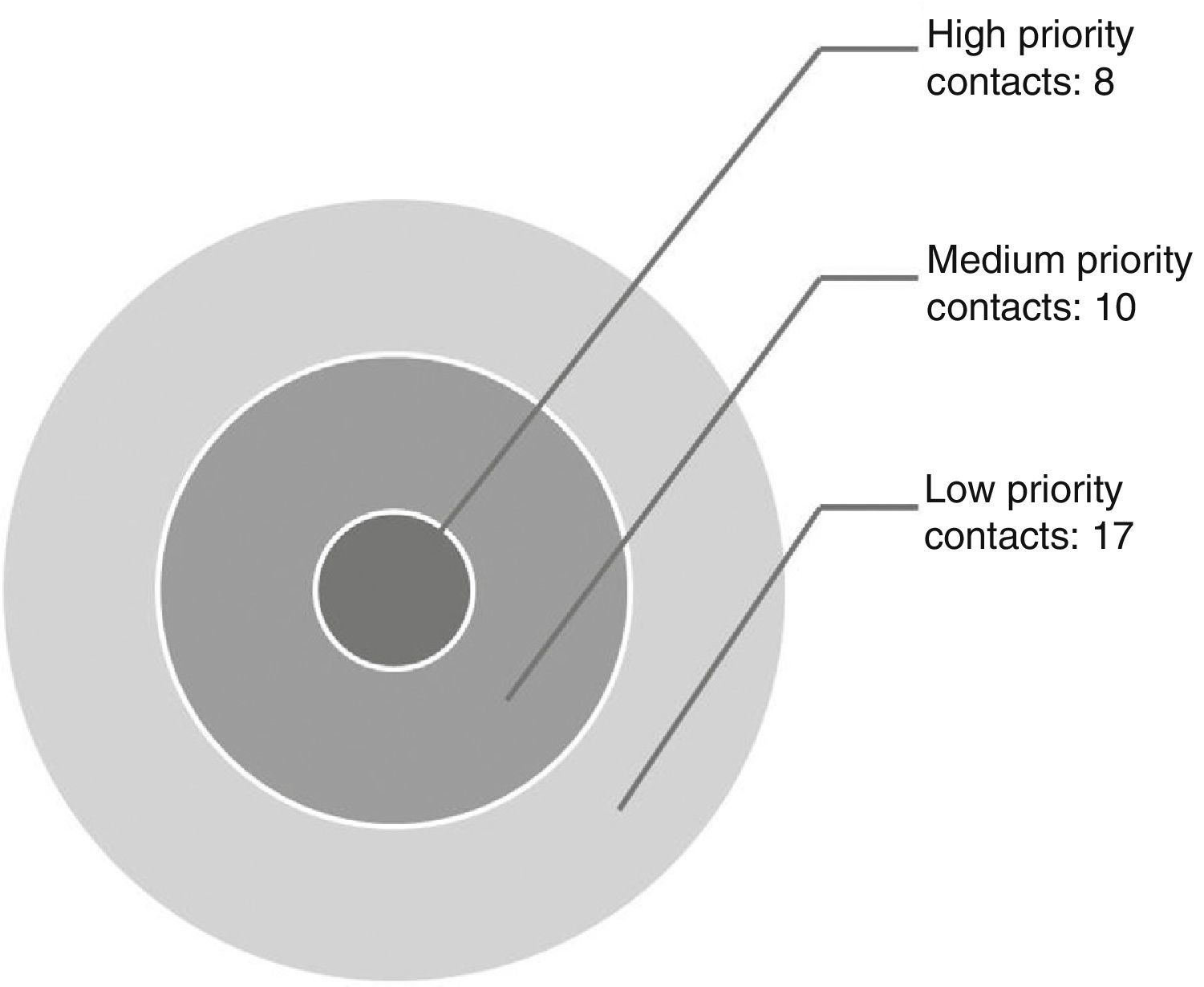

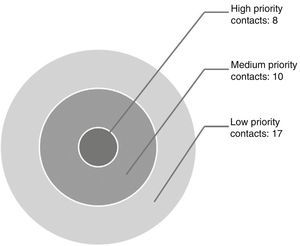

Exposed individuals were censored using the concentric circle approach.11 Contacts were classified as high priority (individuals with contact >6h/day, children younger than 5 years, immunocompromised individuals), medium priority (individuals with daily contact, but <6h/day), and low priority (sporadic contact)5 (Fig. 1).

Mantoux tuberculin testing was performed on all exposed individuals. Results were interpreted after 48h, by measuring the transversal induration.

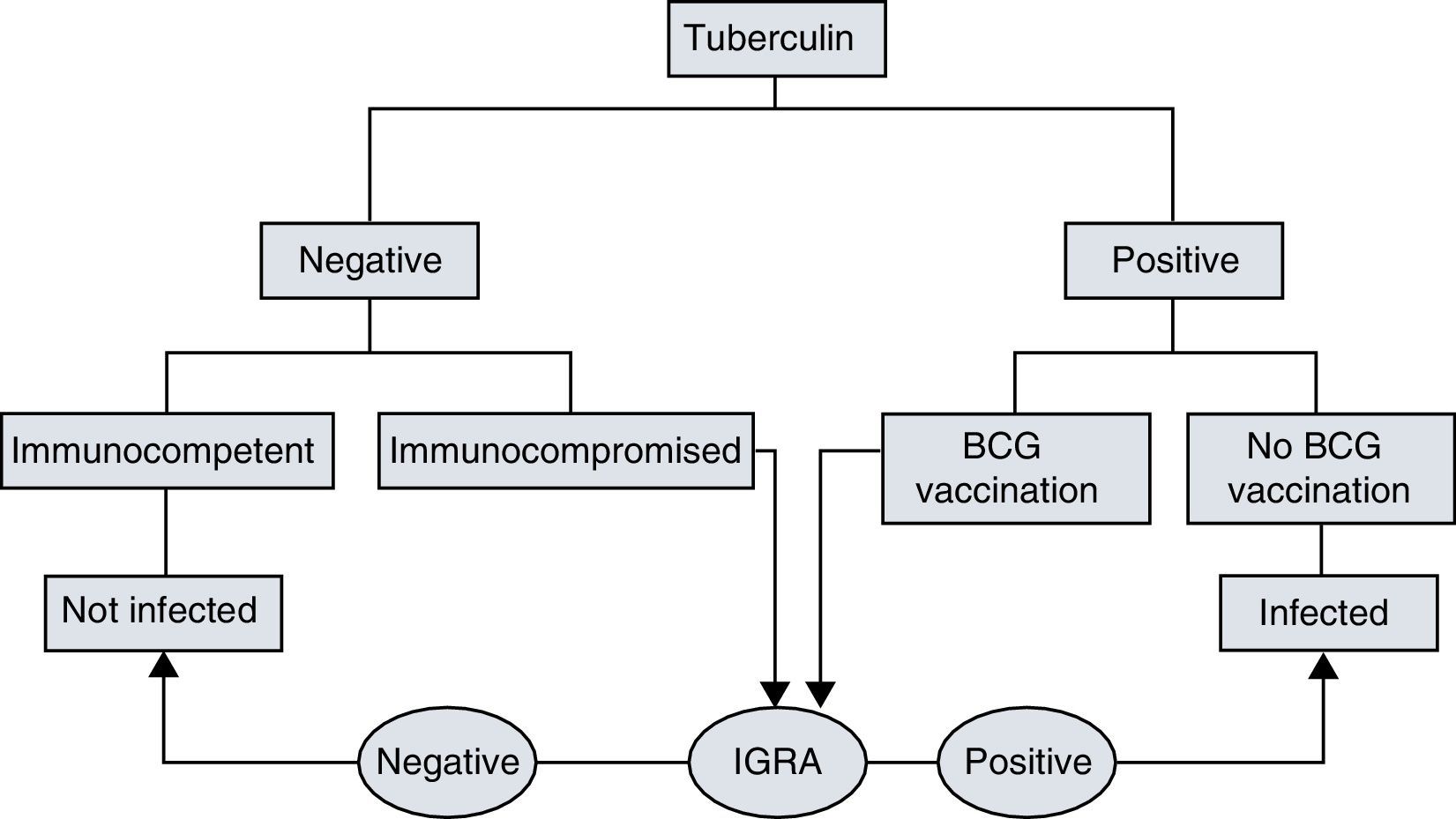

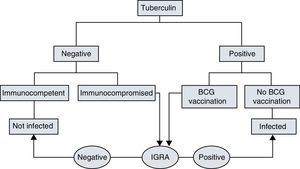

Interferon gamma release assays (IGRA) diagnostics could not be performed in all patients as indicated11 (Fig. 2),12 since at that time the IGRA method was unavailable in our hospital laboratory. We were able send only a selection of samples, designated according to patient risk and age, to the reference hospital (Hospital Universitario Río Hortega de Valladolid).

Tuberculin and IGRA interpretation algorithm.12

To complete the epidemiological study, sputum samples from the index case and 3 exposed individuals who had active disease were sent to the reference laboratory of the National Center of Microbiology in Majadahonda (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain) for genotyping and expanded resistance studies.

High-risk contacts with a negative tuberculin test were treated for probable infection, and the Mantoux test was repeated 2 months later. If the second tuberculin test was negative, chemoprophylactic treatment was administered.

Exposed individuals whose tuberculin test was positive were screened for disease with chest X-ray and serial sputum cultures. After active disease was ruled out, treatment for latent infection (TLI) was administered to contacts classified as high risk, medium risk, or sporadic risk due to concomitant medical conditions. The tuberculin test in contacts who had received BCG vaccination was considered positive if the induration was greater than 5mm in individuals who were close contacts, younger than 20 years, or who presented risk factors; and greater than 15mm in contacts with medium and sporadic risk.11

Exposed individuals who were diagnosed as having active tuberculous disease were referred to the Infectious Diseases Unit of our hospital for administration of anti-TB treatment.

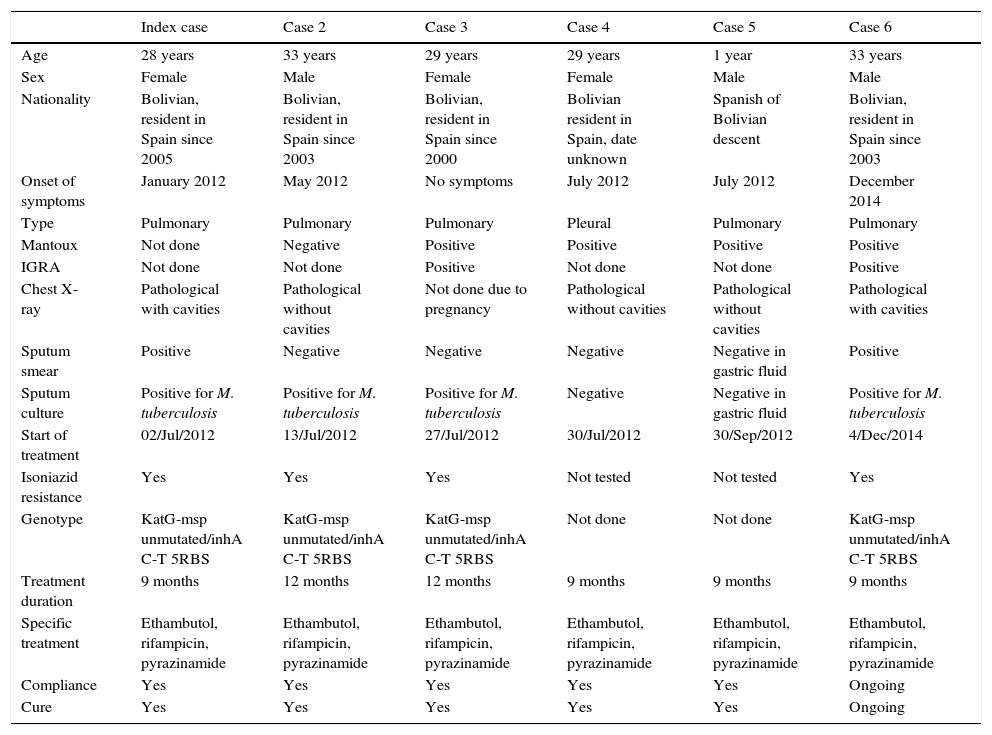

ResultsThe index case was a 28-year-old Bolivian woman, who had been living in Spain for 12 years. Active tracing of cohabitants and contacts produced a total of 39 individuals (Fig. 1). Disease incidence was 15.3% (6/39). Four new cases associated with the index case were detected in the months following identification of the index case. One contact was lost to follow-up. A fifth case, which was not investigated in the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, was diagnosed 2 years later. All cases were of South American origin, except for one boy, who was born in Spain. All individuals had been living in Spain for more than 10 years and none of them had recently traveled to their home country. The Hospital Clínico Universitario was responsible for treatment and follow-up of the cases, and treatment was adjusted when the results of sputum resistance testing were available, in line with current guidelines. Treatment compliance was 100% in all cases, as was cure. Epidemiological characteristics, diagnostic tests and specific treatment of the index case and the 5 derived cases are shown in Table 1.

Epidemiological characteristics, diagnostic tests and specific treatment of tuberculosis cases.

| Index case | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 28 years | 33 years | 29 years | 29 years | 1 year | 33 years |

| Sex | Female | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male |

| Nationality | Bolivian, resident in Spain since 2005 | Bolivian, resident in Spain since 2003 | Bolivian, resident in Spain since 2000 | Bolivian resident in Spain, date unknown | Spanish of Bolivian descent | Bolivian, resident in Spain since 2003 |

| Onset of symptoms | January 2012 | May 2012 | No symptoms | July 2012 | July 2012 | December 2014 |

| Type | Pulmonary | Pulmonary | Pulmonary | Pleural | Pulmonary | Pulmonary |

| Mantoux | Not done | Negative | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| IGRA | Not done | Not done | Positive | Not done | Not done | Positive |

| Chest X-ray | Pathological with cavities | Pathological without cavities | Not done due to pregnancy | Pathological without cavities | Pathological without cavities | Pathological with cavities |

| Sputum smear | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative in gastric fluid | Positive |

| Sputum culture | Positive for M. tuberculosis | Positive for M. tuberculosis | Positive for M. tuberculosis | Negative | Negative in gastric fluid | Positive for M. tuberculosis |

| Start of treatment | 02/Jul/2012 | 13/Jul/2012 | 27/Jul/2012 | 30/Jul/2012 | 30/Sep/2012 | 4/Dec/2014 |

| Isoniazid resistance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not tested | Not tested | Yes |

| Genotype | KatG-msp unmutated/inhA C-T 5RBS | KatG-msp unmutated/inhA C-T 5RBS | KatG-msp unmutated/inhA C-T 5RBS | Not done | Not done | KatG-msp unmutated/inhA C-T 5RBS |

| Treatment duration | 9 months | 12 months | 12 months | 9 months | 9 months | 9 months |

| Specific treatment | Ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide | Ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide | Ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide | Ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide | Ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide | Ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide |

| Compliance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Ongoing |

| Cure | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Ongoing |

Genotyping and expanded resistance results revealed isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (KatG-msp unmutated/inhA C-T 5 RBS); the 4 patients tested had this same strain.

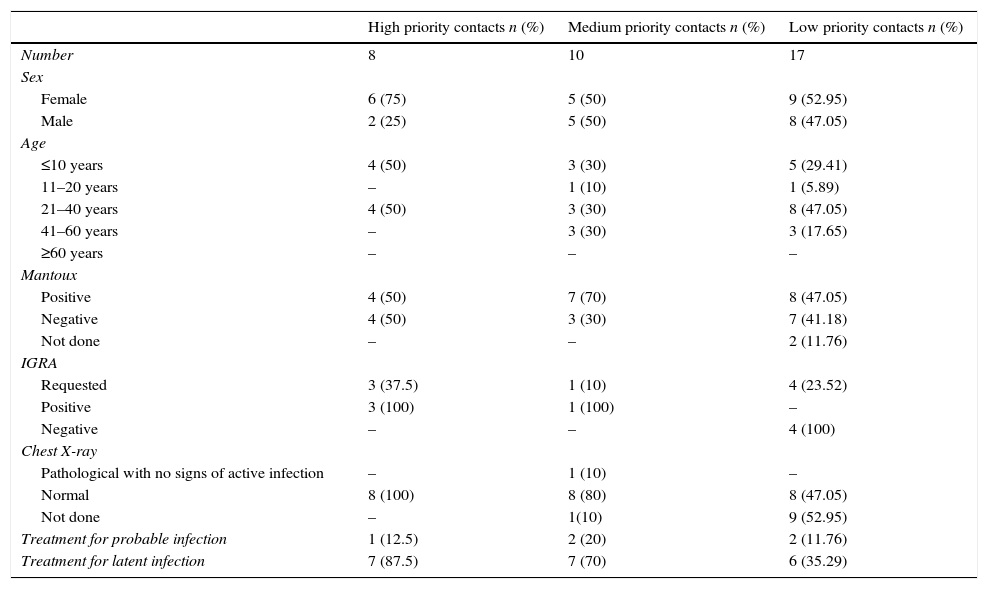

A list of the contacts who did not develop disease is shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of tuberculosis contacts.

| High priority contacts n (%) | Medium priority contacts n (%) | Low priority contacts n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 8 | 10 | 17 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 6 (75) | 5 (50) | 9 (52.95) |

| Male | 2 (25) | 5 (50) | 8 (47.05) |

| Age | |||

| ≤10 years | 4 (50) | 3 (30) | 5 (29.41) |

| 11–20 years | – | 1 (10) | 1 (5.89) |

| 21–40 years | 4 (50) | 3 (30) | 8 (47.05) |

| 41–60 years | – | 3 (30) | 3 (17.65) |

| ≥60 years | – | – | – |

| Mantoux | |||

| Positive | 4 (50) | 7 (70) | 8 (47.05) |

| Negative | 4 (50) | 3 (30) | 7 (41.18) |

| Not done | – | – | 2 (11.76) |

| IGRA | |||

| Requested | 3 (37.5) | 1 (10) | 4 (23.52) |

| Positive | 3 (100) | 1 (100) | – |

| Negative | – | – | 4 (100) |

| Chest X-ray | |||

| Pathological with no signs of active infection | – | 1 (10) | – |

| Normal | 8 (100) | 8 (80) | 8 (47.05) |

| Not done | – | 1(10) | 9 (52.95) |

| Treatment for probable infection | 1 (12.5) | 2 (20) | 2 (11.76) |

| Treatment for latent infection | 7 (87.5) | 7 (70) | 6 (35.29) |

In total, 80% of the patients had received BCG vaccination. Of the contacts who initially presented negative Mantoux results, 14% were positive when the test was repeated 2 months later. TLI was given to all patients who converted and to a contact who showed conversion on an IGRA test. IGRA was positive in 3 of the unvaccinated contacts younger than 20 years whose Mantoux had been negative. No PPD false positives were detected on IGRA testing in individuals who had received BCG vaccination. All other contacts were considered healthy and no further studies were performed.

The incidence of latent infection (LI) was 71.43% (25/35). Of 25 patients with LI, 23 received TLI after active disease was ruled out (20 with LI and 3 converters). The remaining 2 (sporadic contacts) refused treatment. All cases of LI were treated with rifampicin for 4 months. One individual discontinued treatment after 1 month due to pregnancy, and 2 discontinued treatment, as they could not be located during follow-up.

Exposed children with LI continued their treatment period for up to 6 months. No adverse drug event was reported.

DiscussionVery little literature is available on TB outbreaks, either in Spain or around the world.13 This study confirmed the existence of an outbreak of tuberculous disease.

The treatment and chemoprophylaxis of TB is complicated if the infection is caused by bacilli resistant to any of the antituberculous agents. Molecular genetic techniques provided very valuable epidemiological data for characterizing the outbreak and helped us to confirm in our study that a single isoniazid-resistant strain was responsible for the outbreak.

It is essential that contact tracing is undertaken when a case of TB is detected, to determine the real index case and secondary or infected cases.13 Of singular importance, too, is the availability of IGRA diagnostic techniques, to improve the early detection of LI.14

The initial rate of resistance to isoniazid is greater than estimated, probably due to the increase in immigration in recent years. In Spain, between 2010 and 2011, initial resistance to isoniazid was found to be 5.7%; associated factors include crowded living conditions and immigrant status.15

The incidence of primary resistance and multi-drug resistance in the region of Castile and Leon is low, although a slight, insignificant upward trend has been observed. Isoniazid resistance is 3.2%.16

We cannot confidently claim that the strain involved in our outbreak was imported, since the index case has been living in Spain for 12 years, nor can we rule out the possibility that the disease was a reactivation.

In our study, the interval between onset of symptoms and starting treatment was approximately 6 months, and this delay may have led to the appearance of the other new cases, or could at least have been a determining factor in the outbreak. The pulmonary localization in our index case and the fact that she had active disease, along with the intensity of the contact, are significant risk factors for transmission to susceptible individuals.

Treatment compliance in cases and in contacts was high. Only 2 patients refused TLI, as their contact had been sporadic, and 1 patient withdraw due to pregnancy. Another 2 contacts discontinued treatment for no apparent reason and we failed to locate them, despite several attempts. No adverse treatment effects were reported, which helped encourage adherence.

A comprehensive approach to MDR-TB calls for actions addressing all aspects of the disease, from prevention to cure.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

We thank the Pulmonology Department, the Infectious Diseases Unit and the Microbiology Department of the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid.

Please cite this article as: Hernán García C, Moreno Cea L, Fernández Espinilla V, Ruiz Lopez del Prado G, Fernández Arribas S, Andrés García I, et al. Brote de tuberculosis resistente a isoniacida en una comunidad de inmigrantes en España. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:289–292.