To determine the usefulness of NIV in elderly patients (≥75) admitted to a Respiratory Monitoring Unit (RMU) during hospitalization and 1 year later in comparison with the results from the younger age group (<75).

Materials and methodsOurs is a prospective observational study carried out at the Hospital Universitario La Princesa (Madrid). We recruited all patients who were ≥75 years old and were admitted to our RMU during the period 2008–2009 with respiratory acidosis (pH<7.35 and PaCO2>45mmHg) requiring NIV. We gathered data for basic variables as well as sociodemographics, history of previous pathologies, reason for hospitalization and severity, analysis upon admission and the evolution of blood gases at the start of NIV (within the first hour and after 24h), complications and evolution at the 1-year follow-up.

ResultsMean age of the sample was 80.6. The Charlson index was 3.27. About half of the patients had some limitation for performing daily activities. The main reasons for admission were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation and heart failure (HF). There were complications in 36% of the cases (11 renal failure and 6 atrial fibrillation). The survival rate at the 1-year follow-up was 63.21%.

ConclusionsNIV is a good alternative in elderly patients admitted to the hospital with respiratory acidosis. We did not detect differences in mortality during admission between the 2 groups. The elderly patients were more frequently re-admitted than the younger group in the 6–12 months after hospital discharge. This could be due to their poorer functional state after hospitalization requiring NIV.

Determinar la utilidad de la ventilación mecánica no invasiva (VMNI) en pacientes ancianos (≥75 años) que ingresan en una unidad de monitorización respiratoria (UMR) durante el ingreso y al año del alta. Comparamos los resultados con el grupo de pacientes de menor edad (<75años).

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo observacional realizado en el Hospital La Princesa (Madrid, España). Se reclutaron todos los pacientes ≥75 años que ingresaron en nuestra UMR en acidosis respiratoria (pH <7,35 y PaCO2 >45mmHg) y que recibieron tratamiento con VMNI. Se recogieron variables relativas a características sociodemográficas y de la vida basal, antecedentes patológicos previos, motivos de ingreso y gravedad, datos analíticos al ingreso y evolución gasométrica al inicio de la VMNI, en la primera hora y tras 24h, complicaciones y evolución al año de seguimiento.

ResultadosLa edad media fue de 80,6 años. El índice de Charlson fue de 3,27. Aproximadamente la mitad de los pacientes presentaban alguna limitación para las actividades de la vida diaria. Los principales motivos de ingreso fueron la agudización de la EPOC y la insuficiencia cardíaca. En 36 casos se registraron complicaciones (11 insuficiencia renal, 6 fibrilación auricular). La supervivencia al año del seguimiento fue del 63,21%.

ConclusionesLa VMNI es una buena alternativa en pacientes ancianos que ingresan en acidosis respiratoria. No detectamos diferencias en la mortalidad durante el ingreso con el grupo <75 años. Los pacientes ancianos ingresan más entre los 6-12meses posteriores al alta, y esto podría deberse a una peor situación funcional tras un ingreso que requiere VMNI.

With the progressive aging of the population, we are now treating older patients with a greater number of comorbidities and limitations in their daily lives. It is estimated that by the year 2020 48% of the population will have at least one chronic disease and 25% will have some type of associated comorbidity.1 The greater number of comorbidities is mainly found in the over-65 age group.

This new situation leads us to reconsider the management of older patients with poorer baseline situation who are not candidates for aggressive therapeutic measures, such as tracheal intubation, who come to the emergency room with respiratory failure (RF).

In this regard, we feel that non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) plays a crucial role in the treatment of RF in these patients. Although the usefulness of NIMV has been demonstrated in cases of COPD exacerbation with hypercapnic RF (which is the main indication for NIMV in intermediate care units2), acute lung edema, pneumonia in immunosuppressed patients or for intubation weaning,3 its indication in patients with “Do Not Intubate” orders is more controversial, especially in older patient groups.

Currently, articles related with the utility of NIMV in the elderly have been published in respiratory intensive care units (RICU) and by international groups. There are no publications that answer the question of NIMV indication in this age group in our country which have not been done in an RICU, instead of in monitoring units that are more closely in line with the reality of our setting.

The objective of our study was to determine the utility of NIMV in acute situations in senior patients who are hospitalized in a RMU in respiratory acidosis, and to also compare the results with a younger population as well as the results from the 1-year follow-up.

Materials and MethodsStudy DesignA prospective observational study was done in the RMU at Hospital Universitario de La Princesa (HULP) during our unit's first year of activity (2008–2009). HULP is a tertiary hospital in Madrid that provides care for a population of approximately 350000 inhabitants. Our RMU has 4 beds and is integrated on the pulmonology floor of the hospital. It provides non-invasive monitoring of hemodynamic parameters (continuous blood pressure, heart and respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and electrocardiogram) and respiratory support with NIMV or invasive mechanical ventilation in tracheostomized patients. The unit has specialized nurses and a pulmonologist on duty during the morning shift. On afternoon–evening and weekend shifts, there is a pulmonologist on call, so the patients are under the continuous care of a pulmonologist.

Study PopulationAll patients over the age of 75 were consecutively selected for study—this age range was chosen due to the definition of elderly persons by the World Health Organization Mundial—who were admitted to the RMU in respiratory acidosis (pH<7.35 and PaCO2>45mmHg) and needed NIMV. The total number of selected patients was 85. Excluded from the study were those patients who were hospitalized in the RMU for monitoring, those who rejected NIMV or were not considered candidates for NIMV according to the criteria of the pulmonologist, patients who required intubation from the start and those in whom NIMV was initiated on other hospital floors and later were not transferred to the RMU.

The study met with the ethics requirements at our hospital and the patients or their main caretakers signed an informed consent. The patient data were collected from the HULP computer system, which provides access to the computerized medical files.

Study VariablesThe variables collected for study included those related to sociodemographic and baseline characteristics (age, sex, presence of main caretaker, institutionalization, dyspnea according to MRC classification, number of drugs/day, limitations of daily life activities measured with the Barthel test) and previous pathologic history (comorbidities, Charlson index, home oxygen therapy, home nocturnal ventilation, previous hospitalizations, lung function [FEV1] and echocardiographic data in patients with previous diagnosis for HF). We also recorded the reasons for hospitalization in our RMU and severity (APACHE II), analytical data at the time of hospitalization and blood gas evolution (pH and PaCO2) at the start of NIMV and then after 1h and 24h of NIMV, evolution during hospitalization (need for intubation, complications, days of hospitalization and death) and 1 year after follow-up (number of hospitalizations and cause, need for NIMV and hospitalization in the ICU and death during that period).

During the study period, 13 patients were lost to follow-up, and in these cases the patients were contacted by telephone in order to collect information related with the study variables. Information was obtained for 100% of the sample, with no losses registered during the follow-up for causes other than the death of the patient.

Statistical AnalysisIn the descriptive analysis, means, range (maximum and minimum) and standard deviation (SD) were used for the quantitative variables, while the qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. In order to measure the association between the independent quantitative variables, the Student's t test was used, while for the qualitative variables the chi-squared test was used. With contingency tables, we obtained the correlation between 2 qualitative variables and relative risk. The level of significance was assumed with P<.05.

The statistical analysis was carried out with the version 15.0 SPSS program for Windows.

Results85 patients were included for the study, 43 (50.6%) of whom were women. Mean age was 80.6 years (SD 5.93), with a maximum age of 92.

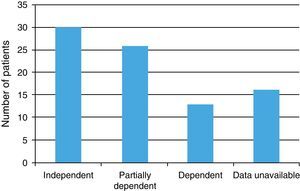

Data for baseline condition were collected (ability to perform activities of daily living, main caretaker, polymedication, degree of dyspnea according to the MRC scale and institutionalization), which are shown in Figs. 1 and 2 and in Table 1. The Barthel index score was 88.19 (moderate dependence).

Distribution of the study population according to limitations for performing daily life activities (eating, getting dressed, bathing, grooming, etc.). The y-axis represents the number of patients. Independent: performs activities of daily living (ADLs) independently; Partially dependent: needs some assistance to perform ADLs; Dependent: is dependent on a caretaker for performing ADLs.

Baseline Life Characteristics (Caretaker, Institutionalized, Dyspnea, Comorbidities, and Drugs/Day) of Our Study Sample.

| Score | % of the Total | |

| Main caretaker | 44 patients | 51.9 |

| Institutionalized | 6 patients | 7.6 |

| Dyspnea (MRC) grade III–IV | 42 patients | 49.3 |

| Drugs/day | 7.01 drugs/day | |

| Comorbidities (Charlson index) | 3.27 (mean score) |

Out of the total sample, 49 patients (57.5%) had a previous COPD diagnosis, with a mean FEV1 (% of predicted) of 39.69% (SD, 12.93%). 42.4% (35 patients) belonged to groups III and IV from the GOLD classification.

51.9% (44 patients) had a previous diagnosis of HF. Mean left ventricular ejection fraction, measured by echocardiogram, was 55.06%. The main causes of HF were diastolic dysfunction (14 patients) and cor pulmonale (12 patients), which represented 60% of the etiologies. In our series, 15 patients (17.5%) were diagnosed with sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (SAHS) and 11 patients (12.9%) presented the effects of tuberculosis.

With regard to respiratory therapies, 44 patients (51.8%) had prescribed long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) and 8 nocturnal ventilation with bilevel pressure system (BPAP) and 2 with continuous pressure (CPAP).

30.5% of the sample (25 patients) presented at least one previous hospitalization in respiratory acidosis requiring NIMV the year prior to the start of the study.

The reasons for hospitalization in our RMU are shown in Table 2. NIMV was started in 90% of cases in the emergency department, and in the remainder it had been initiated on other hospital floors. In all cases, it was under the direction of the pulmonology department. Severity upon admittance was measured with the APACHE II score, which in our sample was 17.71 (probability of mortality 26.2%). Blood gas data (pH and PaCO2) at the beginning of NIMV, after 1h and during evolution after 24h, are shown in Fig. 3.

Evolution of blood gases (pH and PaCO2) at the start of NIMV and after 1h and 24h. Group A: patients over the age of 75. Group B: patients under the age of 75. We detected statistically significant differences in PaCO2 at the start of NIMV and 24h after the start of NIMV. *P<.05. Standard deviation of the mean is represented.

In the emergency department, 10 patients required vasoactive amines, while in 7 nitroglycerine was used. In 9 patients, salbutamol was prescribed in continuous perfusion, and in all cases the vasoactive support and salbutamol perfusion were withdrawn in the first 24h of evolution. At the start of NIMV, hemogram, biochemistry and C-reactive protein were ordered (data shown in Table 3). There was rejection in 5 patients due to claustrophobia, while the rest tolerated NIMV without registering any other withdrawals.

During hospitalization, 3 patients were transferred to the UCI and intubated. Complications were recorded in 36 patients, the most frequent being acute renal failure (11 patients), atrial fibrillation (6 patients), acute lung edema (3 patients), nosocomial pneumonia, and hemoptysis (2 patients). Mean hospital stay was 9.26 days; the death rate was 21.2% (18 patients).

When discharged from the hospital, 43 patients were prescribed LTOT (50.6%), BPAP was prescribed for 24 patients, and CPAP was prescribed for 1. Patients with LTOT at discharge presented increased relative risk for mortality within the first year of 2.2.

In this same period, 21 patients under the age of 75 were admitted to the RMU. We recorded the same data for them as in the over-75 group and these data were compared with the group of older patients (Table 4).

Comparison of Both Age Groups (Under 75 and Over 75).

| <75 Group (SD) | >75 Group (SD) | P Value | |

| Age, yrs | 59.70 (9.45) | 80.21 (15.84) | |

| Females, n (%) | 8 (34.8%) | 43 (50.6%) | <.05 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 66 (5.68) | 55.65 (14.81) | ns |

| FEV1, % predicted | 35.28% (14.84) | 39.08% (13.93) | .071 |

| Previous LTOT, n (%) | 10 (43.5%) | 43 (51.2%) | ns |

| COPD exacerbations, n (%) | 15 (65.2%) | 31 (37%) | <.05 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 2 (8.7%) | 26 (31%) | <.05 |

| PCR, mg/dl | 2.88 (4.22) | 3.79 (7.23) | .465 |

| Leucocytes,/mm3 | 13.370 (4.643) | 10.650 (3.935) | .033 |

| ICU hospitalizations, n (%) | 1 (4.3%) | 3 (3.6%) | ns |

| Hospitalization days | 10.30 (6.67) | 9.27 (5.81) | ns |

| Death, n (%) | 5 (21.7%) | 18 (21.4%) | ns |

| LTOT at discharge, n (%) | 9 (39.1%) | 46 (54.8%) | <.05 |

| MV at discharge (CPAP/BPAP) | 5 (0/5) | 28 (1/27) | <.05 |

SD: standard deviation; ns: not significant.

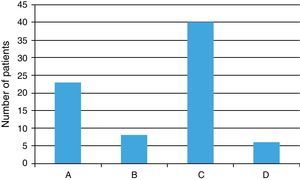

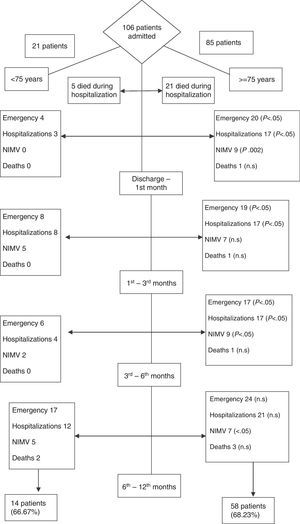

The patients were followed up for 1 year after discharge. This period was divided into 4 stages: from the discharge until the first month (stage 1), from the first month until the third (stage 2), from the third until the sixth (stage 3) and from the sixth until the first year (stage 4). During this period, we recorded the number of visits to the emergency department, hospitalizations and their causes, need for NIMV, admittance to the ICU, intubations, and deaths (Fig. 4). In 13 patients, no clinical data were detected during the follow-up on the electronic medical files, and they were contacted by phone. Out of these 13 patients, 7 had died during the follow-up period.

DiscussionThis is the first study done in a RMU that attempts to answer questions about the indication of NIMV in elderly patients. This group of patients constitutes 21% of the total number of visits to emergency,4 and RF is one of the main reasons for consultation. According to the EPIDASA study,5 the causes of RF in the elderly are multifactorial. With our data, the main causes of RF were COPD exacerbation (36.5%), followed by HF (31.8%), restrictive ribcage pathology, and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome.

The mean age of our cohort was 80.6. 70% of the patients presented limitations for performing activities of daily living to a greater or lesser or degree, and 51.9% needed a caretaker. 65% of the patients were considered to have criteria for no intubation and were not candidates for the ICU. In all cases, NIMV was initiated by the pulmonology department (90% of cases in the emergency department) and the patients were transferred to the RMU. In 3 cases, NIMV failed and the patients had to be intubated. In the study by Nava in patients over the age of 75, 7.3% of the patients with RF and need for NIMV had to be intubated, versus 65% of the group with medication.6 This study, done in an RICU, demonstrates that NIMV patients improved their gasometric data and dyspnea more quickly than the patients who received treatment with medication.

In our study, we did not use a control group of patients treated with medication, but when we compared the data with the younger patients, we did not detect statistically significant differences in the gasometric evolution with recuperation of the parameters in the first 24h (pH 24h in elderly 7.33 vs. 7.36). Nonetheless, we did detect differences in the evolution of PaCO2 (PaCO2 in elderly 64.47 vs 57.76mmHg in the younger age group 24h after the start of NIMV), probably because the patients in the older age group were more often admitted for HF (31.8% vs 8.7%) with slower gasometric resolution,7 and also due to the biology of elderly patients. The overall mortality of the series upon admittance was 21.2% (21.7% in the younger age group). In another study, published by the Scarpazza group,8 mortality was 13%. In this study, the main cause for admittance was COPD exacerbation and no patients with HF were recruited, which represents the most common cause of mortality in our series and could explain the differences in the percentage of deaths in both groups. After hospitalization for HF, long-term survival was around 30% for 6 years,9 with a mean survival of 1.7 years in men and 3.2 years in women.10 In the study by Scarpazza, 1-year survival was 69%, which is similar to our data (63.21%).

By analyzing the parameters associated with higher mortality in our series, the subgroup of patients with LTOT presented higher RR for mortality upon admittance (RR, 1.311) as well as during follow-up (RR 2.0, 6–12 months after hospitalization). Other variables were lower pH (7.19 vs 7.249), higher PaCO2 (88.40 vs 75.50), higher APACHE II score (21.20 vs 18.90) or the Barthel index (75 vs 91). These data are related with the results of the Scarpazza group, where detected factors for prognosis included: lower pH, higher PaCO2, greater number of comorbidities, greater score on the APACHE II index and a lower Glasgow.8 In other studies, age is an independent factor for NIMV failure,11 although according to our data we considered the baseline situation and the gasometric data to be better predictors for NIMV failure because, when comparing the NIMV results between the groups over and under the age of 75, we detected no differences in the mortality or in gasometric correction. It is true, however, that the patients who died in the over-75 group had a mean age of 82.17, compared with 79.87 in the group of patients who survived, without there being any statistical significance.

When we compared both age groups, we observed that the elderly patients presented a greater tendency toward rehospitalization and need for NIMV in the 6–12 month follow-up. One possible explanation could be a poorer functional situation at discharge, which should determine greater fragility and the tendency toward rehospitalization. However, we have not used any measures to verify the hypothesis, and this could be the object of later studies.

Bulow and Thorsager suggest that more studies should be done in order to measure the quality of life in elderly patients who require NIMV after discharge,12 because poorer quality of life may be a possible cause for rehospitalization.

The main limitations in our study were: (a) a relatively small number of patients; (b) lack of a control group of elderly patients treated with medication. Although we have referred to the study by Nava done with 2 groups (NIMV vs treatment with medication), this study was done in an RICU and the percentage of intubations was 65% with medication. Therefore, with current scientific knowledge, we do not consider it ethical to not administer NIMV in cases of hypercapnic RF; (c) the group of patients under the age of 75 is less numerous than the over-75 age group, and the causes for hospitalization were different. HF was also more frequent in the elderly group, although when we compared both groups we found that the benefits of NIMV are similar in both groups.

In conclusion, NIMV is an effective alternative in elderly patients. The improvement in gasometric parameters is similar to that of younger patient groups, and we detected no differences in mortality upon admittance. It is a well-tolerated technique, and in our series there have been no complications derived from NIMV that required it to be withdrawn, although previously at the beginning of NIMV 5 patients refused to use it due to claustrophobia. The 1-year follow-up results are very satisfactory and similar to the younger group, although we detected a greater number of hospitalizations and need for NIMV as well as greater mortality in the 6–12 months after discharge. We think that this could be explained by a poorer functional situation at the time of discharge, and we believe that more studies should be done in order to try to confirm this fact and thus be able to detect the subgroup of elderly patients who could benefit most from this technique.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare having no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Segrelles Calvo G, et al. Ventilación mecánica no invasiva en una población anciana que ingresa en una unidad de monitorización respiratoria: causas, complicaciones y evolución al año de seguimiento. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48:349–54.