The lung is one of the organs most affected by infections caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria, and patients with comorbidities or immunosuppressive therapy are more susceptible.1 Given the increased incidence of these risk factors, diseases caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria are likely to become more frequent in the future. The microbiological study of these species is essential to design the most appropriate treatments.1

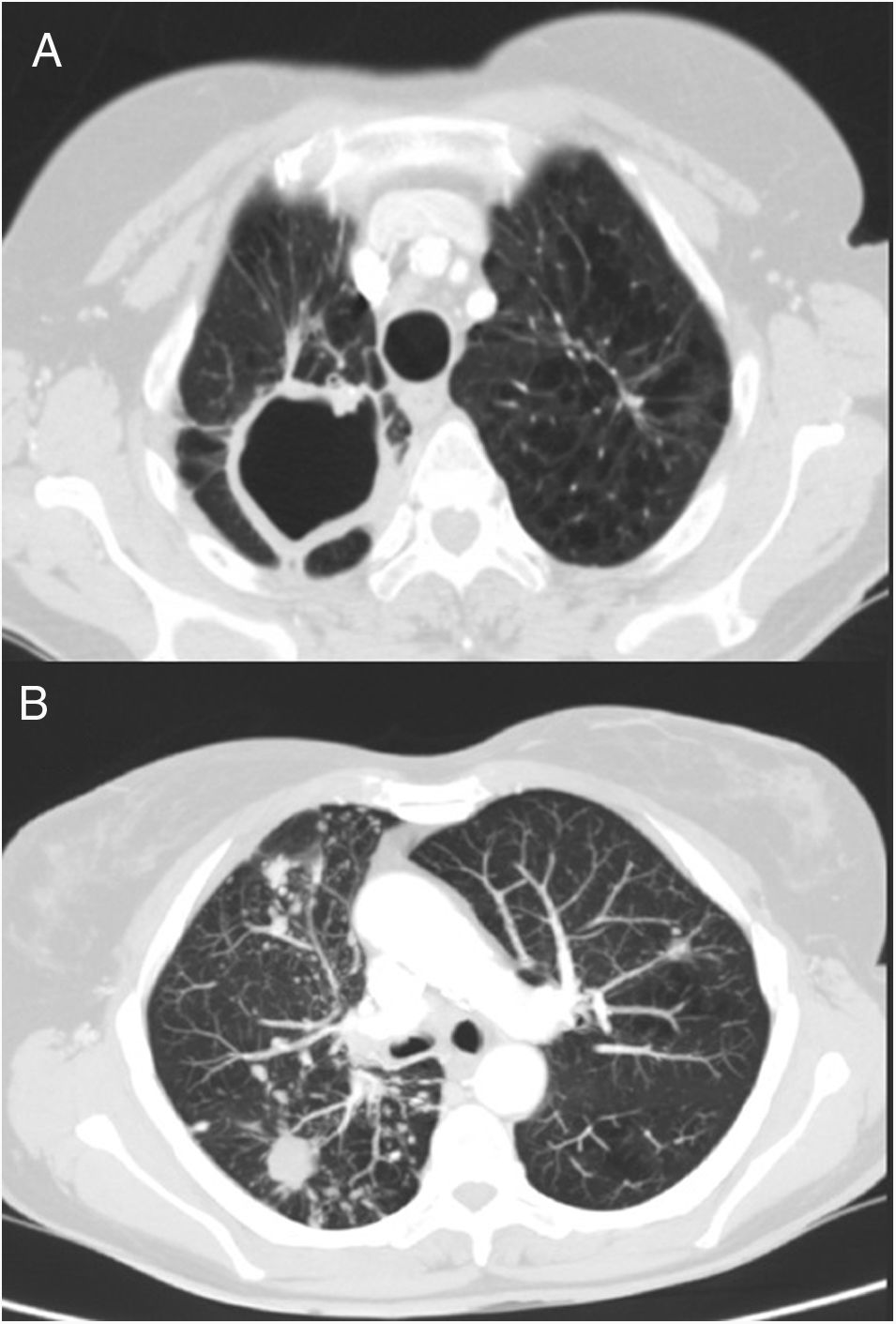

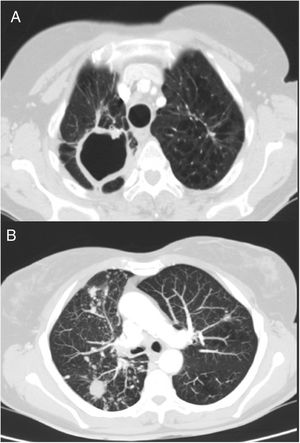

We report the case of a 69-year-old woman who consulted with chronic lumbar pain as her only symptom. Her case history recorded a personal history of a former smoking habit (75 pack-year index), chronic alcoholism, and pulmonary tuberculosis at 41 years of age. After bilateral lung nodules were observed on chest X-ray, a chest computed tomography (CT) was performed, in which sequelae of a previous tuberculous process were visualized, with parenchymal scars and signs of loss of volume in both upper lobes, together with a large cavity and granulomas in the right apex. CT also revealed multiple bilateral and diffuse nodules; the larger nodules (15mm) in the right lower lobe were cavitary, and a micronodular pattern with tree-in-bud distribution was observed in the right middle and lower lobes (Fig. 1). A diagnostic bronchoscopy was then performed, with benign cellularity in bronchoalveolar lavage. Microbiological cultures were negative, while results of mycobacteria cultures were pending. Spirometry testing showed a peak expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/post-bronchodilator forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of 0.6, with FEV1 75%, and FVC 101%. A diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was given and treatment started with tiotropium.

Chest CT. (A) Image of sequelae from previous tuberculous process, with signs of volume loss in both upper lobes and parenchymal scars with large cavitation in right apex. (B) View of multiple bilateral and diffuse nodules, some cavitated, and micronodular tree-in-bud pattern in right lower lobe and middle lobe, associated with the current infectious process.

One week after bronchoscopy, the patient attended the emergency department with a fever of 39°C, cough and a 6-day history of purulent expectoration that did not improve after treatment with amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. She was admitted and treated with levofloxacin and imipenem. Sputum analysis showed the presence of alcohol-resistant bacilli, so given the possibility of pulmonary tuberculosis, treatment was changed to rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative, so pending mycobacteria culture results, and after clinical and radiological improvement, the patient was discharged with the same treatment.

One month later, growth of Mycobacterium malmoense was observed in the culture of 3 different sputum samples and in bronchoalveolar lavage. These were inoculated into solid (Lowein-Jensen and Coletsos) and liquid (Versatrek system) media. The microorganism was identified using the GenoType CM/as kit. The antibiogram showed sensitivity to rifampicin, clarithromycin, and streptomycin, and resistance to isoniazid and pyrazinamide. In view of these results, treatment was changed to rifabutin, ethambutol, and clarithromycin. After beginning this regimen, the patient reported asthenia, hyporexia, and vomiting, so the treatment schedule was changed to daily rifampicin, and ethambutol on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. The patient's side effects resolved, so the dose of ethambutol was gradually increased to a daily dose, with adequate clinical tolerance. The treatment continued for 2 years, after which the patient remained asymptomatic with radiological improvement. Residual lesions persisted in the chest CT, but the size of the right upper cavity and lung nodules decreased.

M. malmoense is the most common non-tuberculous mycobacteria in northern European countries.2 In other European countries, a limited number of cases have been published,3,4 but in Spain, series of only 54 to 20 cases have been described in the last 35 years.5,6 Risk factors for infection are the same as for any other mycobacteria: immunosuppression, previous respiratory diseases, smoking, and alcohol abuse, all of which were present in our patient. Since there are a greater numbers of patients with underlying lung diseases or immunosuppressive treatments, the incidence of M. malmoense infection is likely to continue to increase. Infection with this mycobacteria is clinically significant in about 70%–80% of patients with lung disease. It is also the most important pathogen after Mycobacterium avium complex.7

The isolation of M. malmoense in respiratory samples is probably indicative of infection.8 In our patient, we reached a diagnosis after observing M. malmoense growth in sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage cultures. The microorganism was identified using a molecular technique (GenoType CM/as) that, due to its speed and effectiveness, has now replaced conventional biochemical tests in most laboratories.9 More recently, the MALDI-TOF technique has been introduced for the identification of microorganisms, including mycobacteria. Although it was not used in this case, this technique has already proved its usefulness.10 A 2-year course of a combination of rifampicin (or rifabutin) and ethambutol is recommended for the treatment of these infections, and clarithromycin may be added on a case-by-case basis. Triple therapy has not been shown to be superior to dual therapy, so sometimes the latter is preferred due to frequent adverse effects associated with clarithromycin.1 In our case, the determination of antimicrobial sensitivity was also of great help in deciding on treatment. This was achieved using the broth microdilution technique, using cut-off points established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) for M. avium complex.11

We conclude that although the frequency of respiratory infections caused by M. malmoense in Spain is low, it is probably increasing and is here to stay. Unfortunately, there is little evidence regarding the effectiveness of treatment, although long-term dual therapy seems to be effective in managing this pathology. As with other mycobacteria, microbiological study is important for the management of these infections.

Please cite this article as: Laso del Hierro FJ, López Yeste P, Naya Prieto A, Carballosa de Miguel MdP, Esteban Moreno J, Villar Álvarez F. Mycobacterium malmoense, ¿ha llegado para quedarse? Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:401–402.